Elon Musk is Wrong: Curing Aging Won't Ossify Society

Elon thinks biological aging is necessary to prevent "ossification"; he's completely wrong.

At Davos 2026, Musk called aging “a very solvable problem.”

Then he did what he always does: warned that living “for a very long time” risks “an ossification of society” that may become “stultifying” and “just lack vibrancy.”

He’s been making the same point for years; in 2021 he stated:

“It is important for us to die because most of the time people don’t change their mind, they just die."

He’s also used the political variant: if we live for too long “leadership never dies.”

Strip it to its logical skeleton and the argument is:

Longevity → people stick around longer → people don’t update their beliefs → idea turnover depends on biological death → curing aging = societal stagnation.

Every link in that chain is either absurdly wrong, overstated, or self-defeating.

1. Reversing aging ≠ living forever (category error)

Musk’s logic quietly swaps biological rejuvenation for infinite invincibility, and those are completely different things. Reversing biological aging doesn’t make anyone immortal.

People still die from accidents, violence, infections, cancer, pandemics, disasters, warfare, and plain bad luck. Turnover never goes to zero.

The “leadership never dies” scenario isn’t something that follows from curing biological aging; it’s mostly just a byproduct of inefficient power rotation.

2. Aging is the mechanism of the very rigidity Musk fears

If Musk is worried about rigidity, he’s aiming at the wrong target. The target is aging itself.

There’s a neurobiological paradox sitting right at the heart of Musk’s position that he never addresses: he’s arguing (A) we should preserve the biological process that generates rigidity because (B) death occasionally refreshes it.

That’s completely backwards.

Why do people actually get “stuck in their ways”? Because their brains deteriorate from age.

Cognitive flexibility declines substantially in older adulthood (task switching / set-shifting); adults 60+ show significantly lower flexibility than younger adults.

Processing speed and executive function, the core components of fluid cognition, show well-documented age-related declines.

Openness to experience, the personality trait most tied to intellectual curiosity and receptivity to novelty, is negatively associated with age in large national samples.

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s fundamental capacity to rewire itself in response to new information, decreases with age.

At the circuit level, aging is associated with neural dedifferentiation (reduced neural selectivity), which makes learning less clean and belief-updating more effortful.

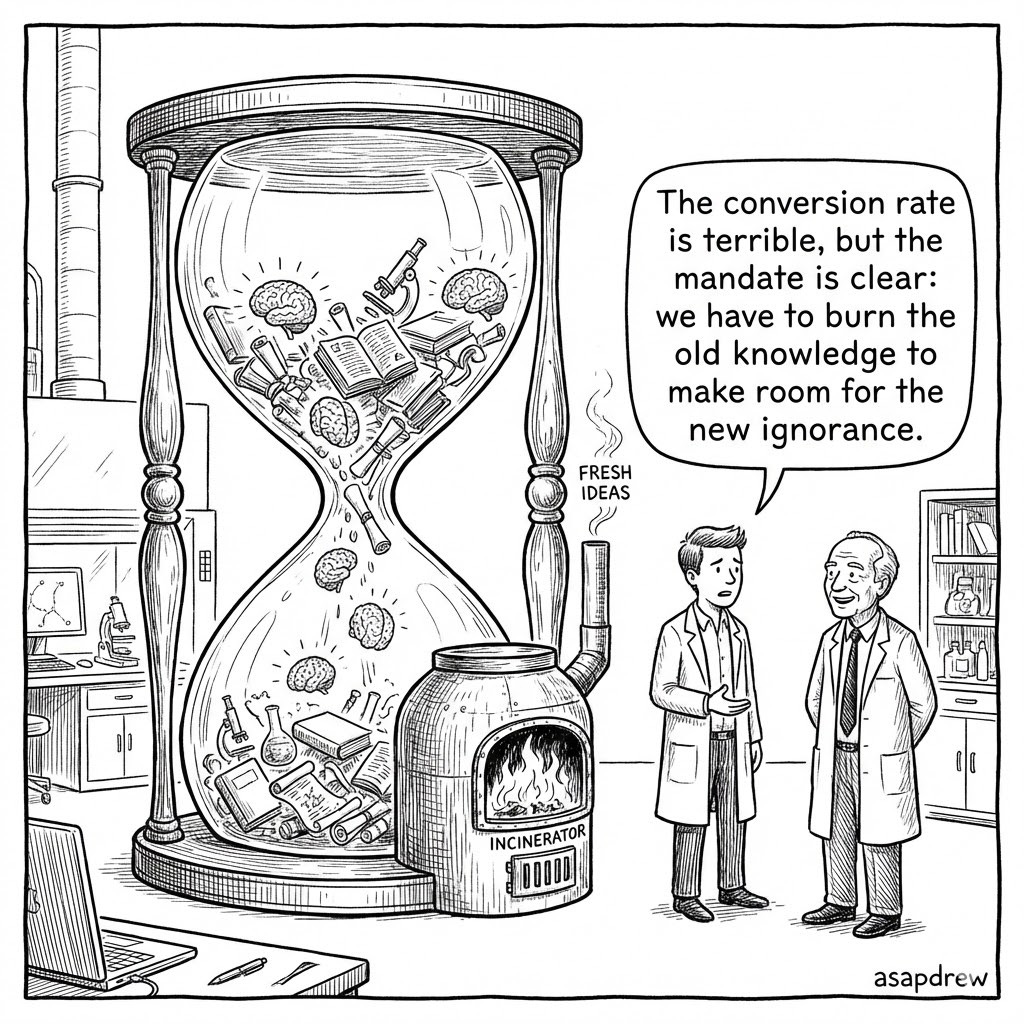

What Musk calls “ossification” is a symptom of the disease he doesn’t want to cure.

And if rejuvenation actually restores the brain to a biologically youthful state, the relevant comparison isn’t “90-year-old mind preserved forever.”

It’s someone with the neuroplasticity, processing speed, and task switching of a young brain who also carries decades of accumulated context, hard-won pattern recognition, and cross-domain intuition.

Brains still prune, consolidate, and forget, so this isn’t an infinite-storage superhero. A 150-year-old with a biologically 25-year-old brain would still be mortal — just able to learn like it’s 25 while carrying a century of context.

Put differently: Musk’s argument is structurally equivalent to “We probably shouldn’t cure Alzheimer’s, because if people remember too much, they might not be open to new memories.”

3. His “people don’t change their minds” premise is overstated and irrelevant

For Musk’s argument to work, you need a near-absolute version of cognitive stubbornness: people can’t update, so you need them to die.

But people update their views all the time.

Scientists abandon paradigms.

Entrepreneurs pivot.

Voters shift.

Openness shows real individual-level variation and responsiveness to environment even as population averages drift with age.

And even if many individuals do update slowly, societal idea-selection is competition-limited, not death-limited. New ideas don’t win because their opponents die, they win because they work.

Better technology displaces worse technology.

Markets reward efficiency.

Status competition drives adoption.

War selects for functional systems over dysfunctional ones.

Death occasionally removes a blocker, sure, but the heavy lifting has always been done by competition, incentives, and demonstrated superiority. Confusing (A) the occasional removal of an obstacle with (B) the engine of progress is a basic attribution error.

4. We already ran the partial test, and society didn’t freeze

No one has ever observed a society with widespread rejuvenation, so let’s be clear: Musk’s ossification claim is conjecture asserted with confidence.

The counterfactual has literally never been run.

What we already have is a massive partial test, and it points in the wrong direction for him. Global life expectancy at birth went from ~32 years in 1900 to ~71 by 2021 and reached ~73 by 2023; more than doubled in a single century.

If longer lives mechanically produced societal ossification, the 20th century should have been a slow crawl into civilizational stasis.

Instead we got the most explosive sustained period of technological, scientific, and economic transformation in human history: quantum mechanics, nuclear energy, antibiotics, the Green Revolution, the microprocessor, the internet, spaceflight, the genomic revolution.

None of this “proves” that extreme rejuvenation has zero risks. But it does kill the word “inevitable.”

“Longer life → ossified society” isn’t a law of nature and the strongest historical trend we have runs in the opposite direction.

5. The reductio: his logic implies shorter lives = more progress

Push Musk’s logic one step further and it collapses under its own weight.

If death is instrumentally good because it refreshes ideas, then higher mortality and shorter lifespans should produce more innovation. Why stop at 80? Why not 60? 40?

High-mortality societies were not innovation utopias. They were trapped by disease burden, instability, low human-capital accumulation, and catastrophically short planning horizons.

You can’t finish a cathedral if you’re dead before the foundation sets. People die mid-project, mid-mentorship, mid-breakthrough, and everything they spent decades learning vanishes with them. The apprentice who was halfway through absorbing a master’s lifetime of tacit knowledge has to start over with someone else, or just doesn’t.

Multiply that across every field, every generation, and you get a civilization that’s perpetually re-learning what it already knew instead of compounding on it. The correlation between rising life expectancy and accelerating civilizational complexity is one of the most robust patterns in human history, and this is a big part of why.

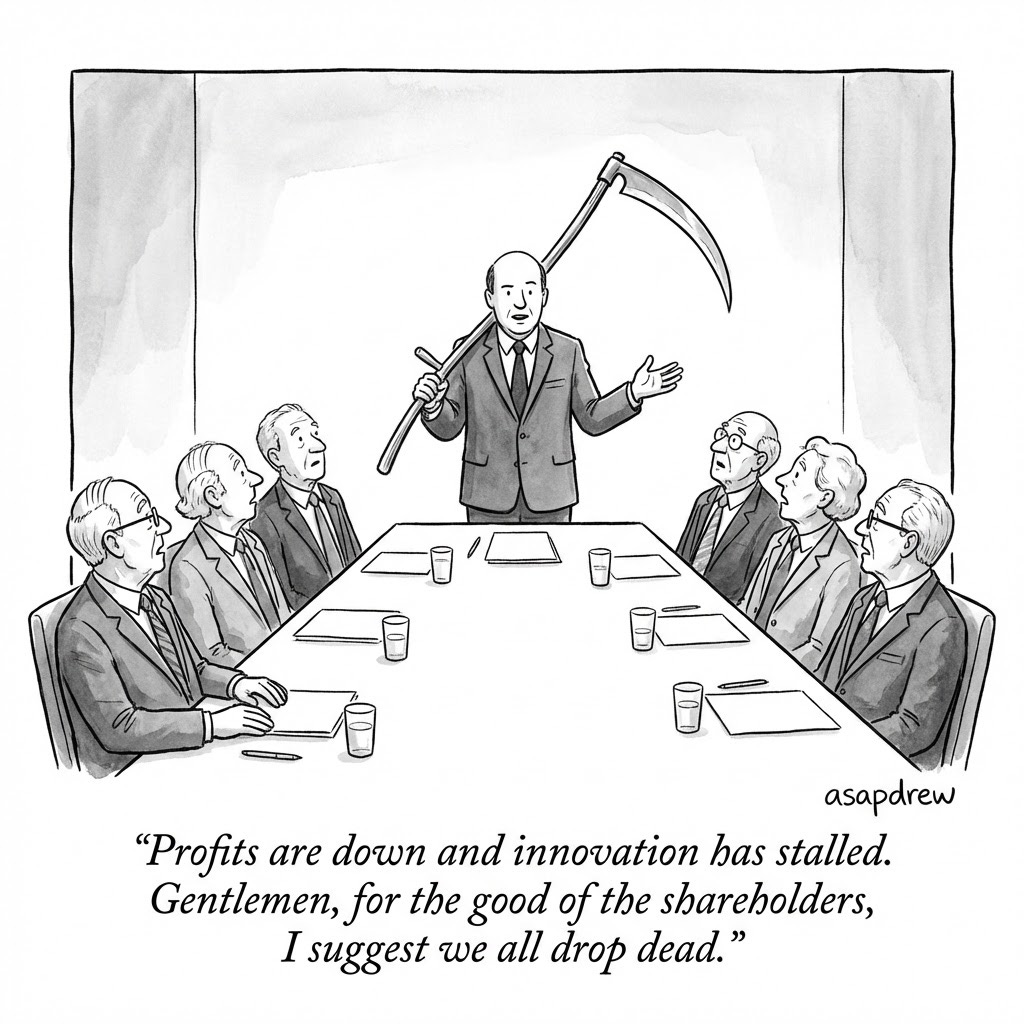

The idea that “people should die so the Overton window refreshes” is trying to solve institutional problems with biological tragedy; the rough equivalent of burning a house down to kill a spider.

For Musk’s story to be true, you need a strong nonlinearity: modest lifespan gains are fine, but somewhere past today a switch flips and extra healthy decades start freezing society. If that tipping point exists, Musk has to explain how it would overwhelm more accumulated human capital with more plastic brains.

6. Ossification is never total, and may even be beneficial

Let’s grant Musk’s framing entirely, just for the sake of argument. “Ossification” in a post-aging world still wouldn’t be absolute.

Exogenous shocks, competitive pressures, technological disruption, and the full force of market selection don’t go away just because senescence does.

Curing aging removes one specific source of turnover (biological decay) while every other source remains fully intact.

There’s also something worth saying that rarely gets said in these debates: in complex systems, some stability is actually functional. (1) Not all change is progress and (2) not all continuity is stagnation. The assumption that more turnover is always better deserves scrutiny of its own.

A world where experienced, cognitively intact people can sustain long-term projects, maintain institutional memory, and compound knowledge across centuries might actually be more adaptive than one that forces a civilizational hard-reset every 80 years and blows enormous resources re-teaching the basics to each new generation.

7. The “funeral effect” evidence refutes his causal story

The steelman version of Musk’s claim goes back to Max Planck:

“Science advances one funeral at a time.”

And there’s a well-known economics paper: “Does Science Advance One Funeral at a Time?” (Azoulay, Fons-Rosen, and Graff Zivin) — that tested a version of this empirically in the life sciences.

After eminent scientists die, outsiders enter those subfields at higher rates, and the resulting work tends to be disproportionately highly cited. Great paper. But if your takeaway is “you need death to advance science” — you are a certified moron.

Sounds like it supports Musk, right? Look closer at the mechanism: the mechanism is incumbent control, not some mystical need for funerals.

Star incumbents dominate attention, funding access, and editorial control during their lifetimes. When they die, the bottleneck loosens and intellectual diversification follows.

You could achieve this same effect a variety of ways with zero deaths from aging, including:

Rotating editorships

Term limits on committee seats

Diversified funding mechanisms

Open-data/open-science norms

Adversarial collaboration incentives

Death happens to be an accidental, barbarically low-resolution way of occasionally achieving what decent institutional adjustments could do cleanly. Anyone who thinks for more than 2 seconds quickly realizes that you don’t actually need death to achieve a refresh.

Additionally, nobody in this debate connects back to the neurobiology: gatekeepers themselves are aging and gatekeeping may be a direct byproduct of aging! The star incumbents dominating various fields aren’t just powerful… they’re old and getting older, which means their cognitive flexibility, openness to new ideas, and willingness to update are actively degrading in real time.

Aging creates the rigidity Musk worries about at the individual level and synergistically feeds into institutional lock-in by ensuring that the people sitting on panels, editing journals, and controlling funding are becoming biologically less capable of recognizing good new ideas the longer they hold those positions.

Rejuvenation would actually attack both problems at once: (1) keep the institutions populated by minds that can still flex, while (2) buying time to implement the structural reforms that address gatekeeping directly.

When “death improves innovation” in some narrow context, that tells you something about incumbent control but nothing about whether humans should die of old age.

And even granting the dynamic some historical validity, there’s no reason to assume it stays net-positive going forward. The past doesn’t always extrapolate to the future; the inverse could occur.

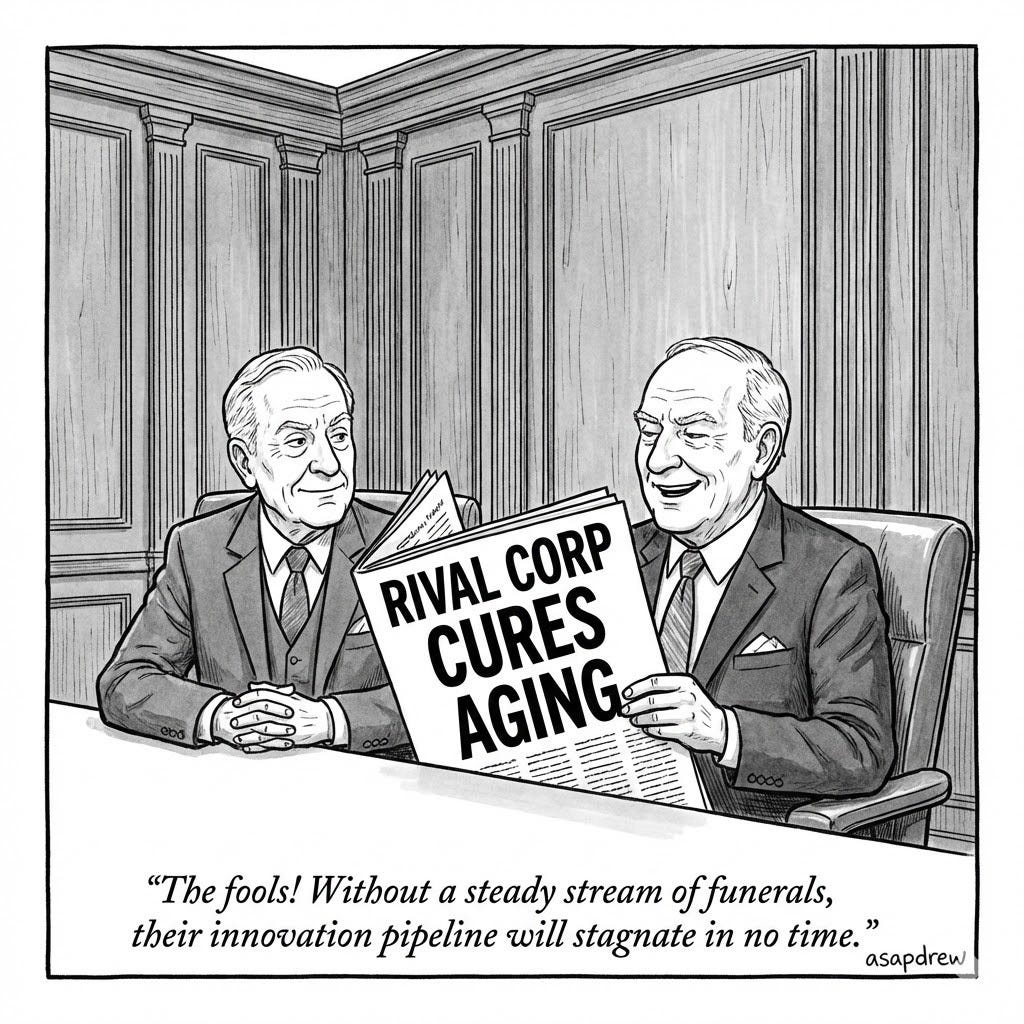

As knowledge burdens rise and it takes longer to reach the frontier, each funeral gets more expensive. Losing a frontier-capable mind in 1920, when certain PhDs took a few years and the relevant literature fit on a bookshelf, is a very different proposition than losing one in 2025, when reaching the cutting edge requires a decade-plus of specialized training.

The cost of the “refresh” keeps climbing while the pool of people capable of doing frontier work keeps shrinking. At some point the funerals start costing more than whatever gatekeeping bottleneck they break and we may already be past that point.

8. Gatekeeping is the actual bottleneck, and it has nothing to do with lifespan

Real ossification-like dynamics are happening right now, and not one of them has anything to do with how long people live:

Peer review has become structurally conservative: “weaknesses” routinely dominate “strengths” in scoring and negative information is overweighted. NIH’s CSRAC notes that NIH review is frequently criticized as risk-averse — favoring “sure thing” established ideas over potentially high-impact but unproven ones.

Papers and patents have become less disruptive over time, as measured by formal disruption indices. That’s exactly the kind of “ossification” people worry about, and it’s happening under ordinary human mortality.

Tenure systems, bureaucratic red tape, reputational penalties for failure, and risk-averse funding structures stifle innovation every day through institutional design, not biology.

If ossification is real today (and the evidence suggests it is), it’s happening despite people dying on schedule. Death clearly isn’t solving it.

Whatever’s behind declining disruptiveness in science, “people aren’t dying fast enough” isn’t a serious diagnosis.

9. The “leaders never die” fear is a governance design failure

Musk’s strongest political worry: very long lives could mean longer entrenchment in high-power positions.

Even so, death is a grotesquely inefficient mechanism for leadership rotation. Functional societies already rotate power through term limits, elections, party competition, mandatory transparency, anti-corruption enforcement, corporate governance, board controls, antitrust regulation, forced divestment rules, and competitive entry.

If your political system needs people to biologically die to rotate leadership, the system is poorly designed. The answer is to fix the governance via reform, not to defend biological aging and death as some kind of implicit social policy.

And there’s a deep irony here: even under Musk’s own fear model, rejuvenation reduces the worst version of gerontocracy.

The actually terrifying scenario: elderly leaders with decaying cognition clinging to power they can no longer competently wield. Normal aging drives straight toward that outcome. Rejuvenation drives away from it by keeping cognition intact.

If Musk genuinely worries about gerontocracy, opposing rejuvenation is self-defeating; he’s locking in the exact failure mode he claims to fear.

10. The “meaning through scarcity” myth

Underneath all the policy-level arguments, there’s a lazy philosophical assumption doing quiet work: that death gives life urgency, and without it people would just sit on the couch forever.

Look around: plenty of people waste their lives while fully aware they’ll die.

The vast majority of humans coast through life in a default state of sedated homeostasis, not because they lack awareness of mortality, but because that’s how people actually behave.

The only time death reliably produces urgency is when someone gets a terminal diagnosis, and even then it’s hit or miss. If knowing you have maybe 50 years left isn’t enough to light a fire under most people, removing the deadline won’t suddenly make them lazier. You can’t lose urgency that wasn’t there.

The deeper problem with the premise is that it misreads what actually drives the people who do act with urgency. Competition, status-seeking, curiosity, resource acquisition, dopaminergic reward circuits: these are biologically hardwired.

These traits don’t depend on mortality anxiety. Nobody builds companies, writes symphonies, or crosses oceans because they’re running from the grim reaper. They do it because the drive to compete, create, and discover is baked into the species.

And remember: existential risk never goes away… there’s still scarcity! Curing aging doesn’t make you bulletproof. Car crashes, pandemics, wars, asteroids, entropy: the universe stays hostile regardless. Even in a post-aging world, the stakes of being alive would be fully intact.

11. The compound interest of human capital

Musk’s model quietly assumes that “long lives keep old ideas around, so innovation slows.” The actual evidence says the opposite.

Knowledge burdens keep rising; reaching the frontier increasingly requires longer training and narrower specialization.

And even with better tools than ever (compute, automation, instrumentation, ML) —measured research productivity has fallen across domains: more researchers and more effort are required to get the same incremental progress.

That pattern is usually chalked up to diminishing returns. But there’s a second possibility that actually strengthens our argument: a human-capital constraint.

If that’s even partially true, then celebrating death as “refresh” is the dumbest possible response: it destroys the scarce input you’re bottlenecked on.

As the knowledge barrier rises, you need a thicker right-tail of frontier-capable minds to even reach the edge. If that tail is thinning per capita (demographic shifts, fertility selection pressures, de novo mutational load, etc.), then “ideas are harder to find” is exactly what you’d expect — even in a world with vastly better tech.

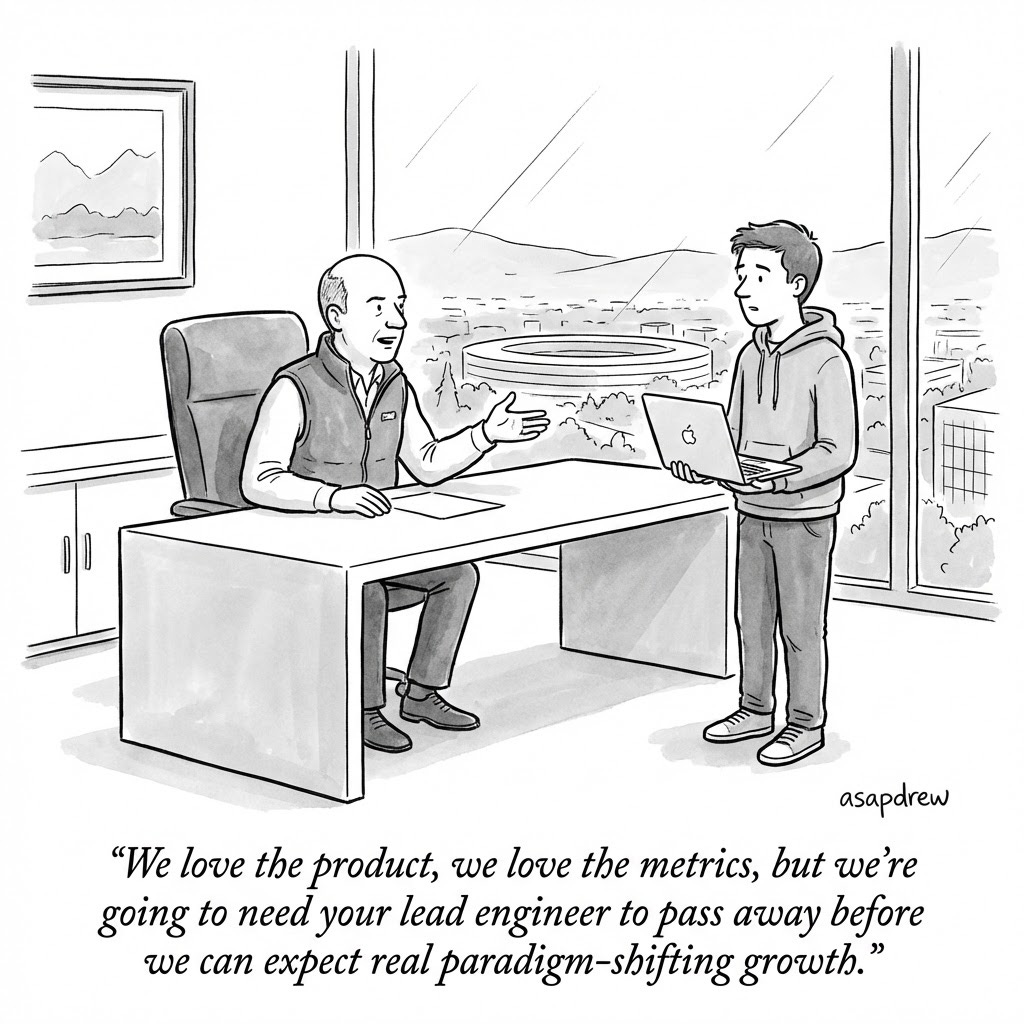

The mean age of “great achievements” for Nobel-caliber work and major inventions rose by about 6 years over the 20th century. In biomedicine, first major independent grants tend to arrive in the early 40s. The productive window between finally reaching the frontier and the onset of age-related decline keeps narrowing.

Think about the timeline we currently accept as normal: ~25 years training a mind, maybe 30-40 years of peak output, and then that mind degrades and dies, taking everything it ever learned, all its institutional memory, all its cross-domain synthesis capacity, into the ground. We do this over and over, billions of times, and call it inevitable.

Death is the ultimate destroyer of human capital. In a world where knowledge burdens keep climbing, the answer to innovation isn’t “more funerals.” It’s more healthy years after you finally reach the frontier. That’s what rejuvenation actually does. Imagine von Neumann, Curie, or Ramanujan with 200 years to compound their knowledge. That’s what we’re leaving on the table.

Either way, death makes it worse: it truncates the already-short window between “finally reached the frontier” and “aging starts degrading the machine.”

12. The counterfactual is far worse than ossification

Musk worries about a frozen society. But the status quo, where we don’t cure aging, doesn’t deliver dynamism either.

What it delivers is a specific, measurable catastrophe:

The morbidity tax. A global demographic inversion is already underway. Without rejuvenation, a shrinking base of young workers gets stuck spending an ever-larger share of economic output on palliative care for a massive, chronically ill, cognitively declining elderly population. That’s what real societal ossification looks like: an economy consumed entirely by geriatric medicine, with nothing left over for innovation, exploration, or risk-taking.

The productive window collapse. As the age of great achievement drifts later and biological decline stays on schedule, the window of peak contribution narrows toward a knife’s edge. Aging doesn’t just kill people. It systematically truncates the civilizational return on every dollar invested in education and training.

The dysgenic trajectory. Under current fertility differentials, death doesn’t refresh the talent pool. It drains it. High-capital populations are below replacement. Their accumulated knowledge dies with them. This dynamic leads somewhere very dark, and it deserves a closer look.

The picture we’re living through right now isn’t a choice between “dynamism with death” and “stagnation without it.” It’s stagnation via morbidity, shrinking talent pools, compressed productive windows, and institutional risk-aversion, all unfolding with normal lifespans and normal death rates.

13. Death can produce worse ossification than curing biological aging ever could

This is the argument that Musk and every other “pro-death for dynamism” thinker never grapples with, and it flips the entire debate.

Musk frames two scenarios: (A) cure aging, risk ossification from entrenched people; or (B) keep death, enjoy fresh turnover and dynamism. He assumes (B) is the safe default.

Under realistic demographic conditions, it’s not. The death-included trajectory produces a form of ossification that’s categorically more severe, more permanent, and more irreversible than anything the no-death scenario could ever generate.

Consider the two types of ossification side by side.

Musk’s version is soft and correctable. Long-lived people resist new ideas, sure, but the capacity for innovation still exists in the population. The cognitive hardware is intact. Stubborn incumbents blocking change is a behavioral and institutional problem you can solve with governance reform, competitive pressure, institutional redesign, or simply waiting for the better idea to prove itself in the market. Real but shallow. The underlying human capital is preserved.

Death-driven ossification is hard and potentially permanent. High-human-capital populations, the ones disproportionately responsible for scientific discovery, frontier technology, institutional design, civilizational maintenance, are universally below replacement fertility. They delay reproduction, have fewer children, invest heavily per child. Meanwhile, populations with higher fertility rates and shorter generational cycles keep expanding. Every generation, the global distribution of heritable cognitive traits (general intelligence, conscientiousness, openness) that correlate with civilizational complexity shifts.

Let death work across a few generations and the consequences could be highly damaging for humanity. The high-capital populations age, decline cognitively, die on schedule, taking their compounded knowledge and institutional memory with them. The next generation is smaller. The one after that, smaller still. The replacements, both within and across populations, carry a lower baseline of the evolved genetic traits that built the systems they’re inheriting. At some point the frontier may hit a complete roadblock because the cognitive substrate required for frontier work has eroded at the population level.

And this version of ossification? You can’t “institutionally reform” your way out of it. When Musk’s version occurs (stubborn leaders blocking new ideas), you rotate them out, defund them, outcompete them, wait them out. When trait-level ossification sets in, there’s no institutional fix.

You can’t term-limit your way out of a shrinking supply of frontier-capable cognitive talent or design a grant structure that compensates for the absence of people capable of doing the work. The civilization regresses, and it stays regressed, because the traits required to generate a renaissance have been selected out.

Recovery would take either millennia of re-evolution or biotechnological intervention that the degraded population may no longer have the capacity to develop; this becomes a civilizational trap door with no handle on the inside.

The blunt comparison:

No-death ossification (Musk’s fear): Same people, intact cognition, resistant to new ideas. Correctable via institutional reform, competition, and time. Innovation capacity preserved. Reversible.

Death-driven ossification (the actual risk): Cognitive substrate erodes generationally. Frontier-capable population shrinks. Institutional memory destroyed every 80 years. Innovation capacity permanently degraded. Potentially irreversible without the very biotech the degraded population can no longer produce.

Musk worries about a society that won’t change. The death-included default delivers a society that can’t change. One of those is orders of magnitude worse than the other.

The deepest irony of his position: the very mechanism he celebrates, biological death cycling out the old to make room for the new, is the mechanism that under current fertility differentials guarantees a future where there is no “new” capable of advancing beyond the old.

Permanent stasis, not because leaders won’t step aside, but because nobody left can lead at the frontier. Curing aging is one of the only interventions that directly attacks this, by removing the biological clock constraint that forces high-capital individuals to choose between reproduction and contribution, and by preserving the existing stock of frontier-capable minds instead of feeding them into the furnace every 80 years.

The bottom line

Musk’s “ossification” argument isn’t remotely convincing.

The rigidity he fears is plausibly caused by aging itself, since normal aging degrades executive function, cognitive flexibility, and openness to experience.

The strongest historical trend we have, life expectancy more than doubling in a century, produced the most dynamic era of innovation in human history.

Where “death helps” in specific domains like science, the evidence points to institutional gatekeeping, not some cosmic necessity for funerals.

And worst of all, the death-included trajectory risks a far more severe and irreversible form of ossification through population-level trait erosion, delivering a civilization that doesn’t just refuse to advance but genuinely can’t.

There’s a final irony worth noting. Musk talks routinely about abundance, being pro-humanity, reaching Mars, and building a Kardashev-scale civilization.

Every one of those goals is bottlenecked by the same thing: not enough frontier-capable minds working on hard problems for long enough.

Curing biological aging is probably the single largest force multiplier for everything Musk claims to want.

More healthy years means more compounding of expertise, more people pushing the frontier simultaneously, more institutional memory preserved, more time to tackle problems that take centuries to solve.

If you actually believe in abundance and interplanetary civilization, opposing rejuvenation is like sabotaging your own engines mid-launch.

The death of the individual is not the engine of progress… it is the single greatest destruction of data, potential, and compounded human capital in the known universe.

Defending death as social policy is civilizational self-sabotage.