Claude Opus 4.6: Longevity Escape Velocity (LEV) Prediction (as of 2026)

Claude Opus 4.6 predicts when humanity achieves LEV.

Preface: I had Claude Opus 4.6 predict (1) IF (YES/NO) + (2) WHEN (~YEAR) humanity achieves longevity escape velocity (LEV). The initial output was riddled with mistakes and logical errors (yes even “Claude Opus 4.6 extended thinking” makes some bad errors… and I still think it’s a great AI model… not currently as-good-as GPT-5.2-High/Pro in accuracy… but more useful for certain tasks and less woke/censored). After pointing out its thinking errors, Opus 4.6 revised LEV odds down from ~45% by 2050 to ~30% by 2050.

In the process, I had to: (1) guide Claude to be more accurate (it cited wrong stats) and include all modalities (it missed a lot of key developments e.g. Michael Levin and bioelectric fields despite “researching” for a long time); (2) grill Claude on its “bridge therapy” optimism (rapamycin and NAD+ are highly questionable) and inform it about healthy user bias muddying the data; and (3) bash Claude on its borderline-braindead AI “drug discovery” optimism (nauseating how misinformed people are… it’ll get great one day… currently it’s not remotely close to developing a drug that’s a “massive improvement” over the field… let alone a massive anti-aging breakthrough).

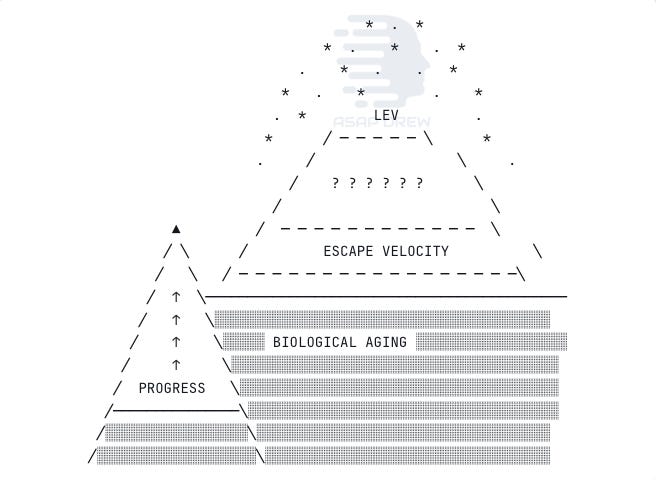

Longevity escape velocity (LEV) is the point at which medical advances extend remaining life expectancy by more than one year for every year that passes.

Once you cross that threshold, you’re outrunning the clock:

Each year of aging is more than offset by the therapies developed during that year.

You stop dying of “old age” not because aging is cured in one shot, but because the rate of progress in reversing it exceeds the rate at which it kills you.

It’s an analogy to escape velocity in physics, the speed at which you break free of a gravitational pull entirely. In practice, achieving LEV for even one cohort would mean that group effectively has indefinite lifespan, barring accidents, violence, or diseases we haven’t yet learned to treat.

The biological proof-of-concept for age reversal is stronger than most people realize.

Partial epigenetic reprogramming extended remaining lifespan in aged wild-type mice by 109% in a 2024 study using a translatable gene therapy vector.

The first human trial of partial epigenetic reprogramming received FDA IND clearance on January 28, 2026.

Adjacent fields like bioelectricity, morphoceuticals, and chemical reprogramming are generating complementary evidence that aging may be attackable from multiple angles at once.

But the question that actually matters is not can we reverse aging… It’s:

Will we actually try, and if so, when?

Probably not soon enough or hard enough.

There’s no serious political constituency for aging research. No Manhattan Project on the horizon. The incentive structures of pharma, government, and academia are aligned against the kind of coordinated assault this problem requires. The field has barely been attempted, and the forces preventing it from being attempted aren’t weakening; they might be getting stronger.

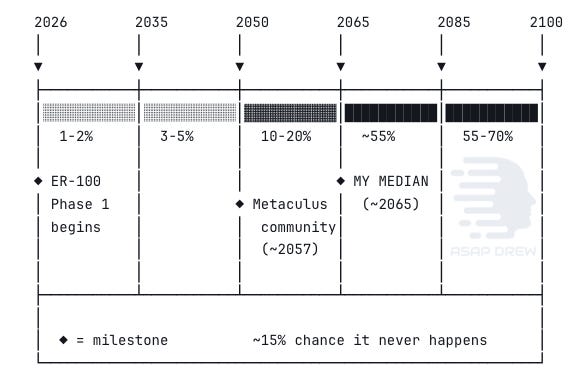

Claude Opus 4.6 Extended: ~30% by 2050, ~55% by 2065, ~70% by 2085.

Median: ~2065 for the first cohort.

Metaculus community forecasts sit at: (1) ~2057 for strict LEV and (2) ~2066 for even a softer 0.75 years/year target, with a 13.4% probability assigned to “never” on the latter.

Claude Opus 4.6 sits near the Metaculus community, maybe slightly more pessimistic.

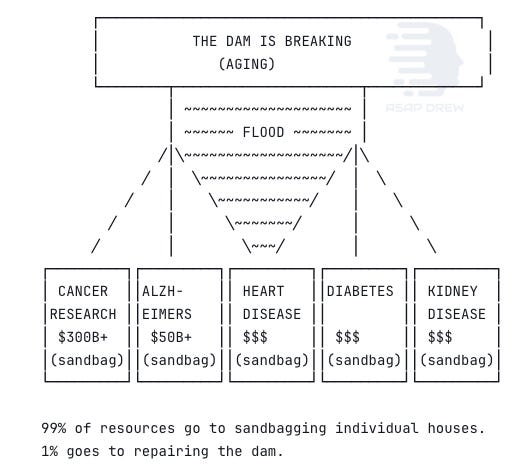

The most underfunded problem in human history (and that probably won’t change fast)

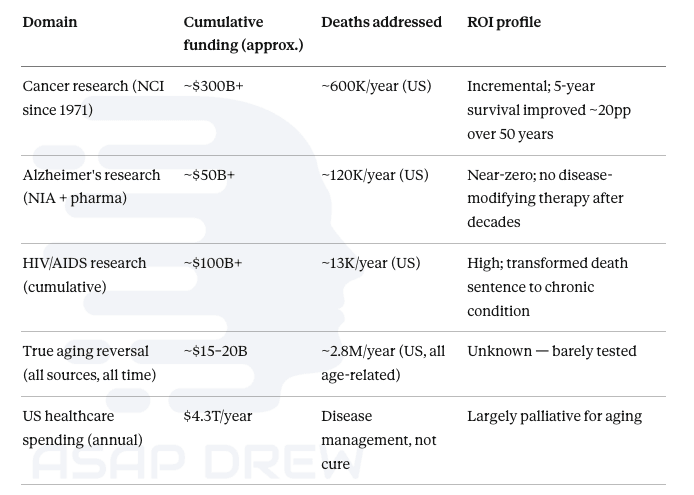

The resource picture is damning. The NIA spends about $346 million annually on aging biology, which is less than 1% of NIH’s $47 billion budget. The National Cancer Institute alone gets $7.2 billion. The entire private longevity sector raised $8.49 billion in 2024 across 331 deals, roughly what Pfizer spends on R&D in a single year. Proposed 2026 budget cuts would slash NIA grants by 45.5%.

Aging is the primary risk factor for cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, diabetes, kidney disease, and immune decline.

Together these account for about 75% of all deaths and 80%+ of healthcare spending in developed nations. The US spends around $4.3 trillion annually on healthcare, most of it going to age-related chronic disease management.

The “longevity dividend” has been estimated at $38 trillion for a single year of global life expectancy gain. An intervention addressing the root cause of 75% of human disease receives less funding than individual disease categories it would largely render moot.

The field hasn’t failed. It has barely been attempted.

That framing is correct but incomplete. The harder question is why it hasn’t been attempted, and what would need to change.

There’s no natural political constituency for aging research the way there is for cancer (survivors, advocacy groups, ribbon campaigns) or HIV/AIDS (activist movements that literally changed FDA policy). Aging affects everyone equally, which paradoxically means nobody organizes around it with urgency. The gerontological establishment has historically been hostile to “anti-aging” framing, preferring “healthy aging” and “compression of morbidity,” goals that don’t require and often actively discourage radical thinking.

Pharma’s incentives are misaligned (in part due to regulations pushing them in this direction). There’s far more money in disease management than in curing the upstream cause. A successful aging reversal therapy would cannibalize the revenue streams of every major drug company’s top sellers.

The FDA doesn’t classify aging as a disease or treatable condition, so every longevity therapy must target specific disease indications, multiplying development time and cost.

The WHO added aging-related codes to ICD-11, but US regulatory practice hasn’t followed.

NCI has spent over $300 billion since Nixon’s War on Cancer in 1971, producing real but incremental gains: roughly 20 percentage points of improvement in 5-year survival rates across half a century.

Alzheimer’s research has absorbed $50+ billion with essentially zero disease-modifying therapies approved. HIV/AIDS research, at around $100 billion cumulative, is the clearest success story, transforming a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition. True aging reversal has received perhaps $15–20 billion total across all sources in its entire history, most of that in the last 5 years. Yet aging kills roughly 2.8 million Americans per year through its downstream diseases, dwarfing every other category.

The historical analogies for what happens when resources match scale (Manhattan Project, Apollo, mRNA vaccines, Human Genome Project) are appealing but misleading in one critical respect: each had a clear political catalyst.

Manhattan had the existential threat of Nazi Germany. Apollo had Cold War prestige competition. mRNA had a global pandemic killing millions in real-time. Aging has none of these. It kills 100,000 people per day, but it kills them slowly, individually, and “naturally,” and that word does enormous rhetorical damage.

A “Manhattan Project for aging” at $20 billion/year is not coming.

Not because it wouldn’t work or because the ROI wouldn’t be spectacular, but because nobody with the power to allocate those resources has any incentive to do so. The real question is whether private capital, billionaire philanthropy, and incremental regulatory shifts can substitute, and how long that slower path takes.

The $8.5 billion landscape (it’s not that much)

Global longevity funding reached $8.49 billion across 331 deals in 2024, more than doubling from $3.82 billion in 2023.

To put that in perspective: Eli Lilly alone spent $9.3 billion on R&D in 2023.

The entire longevity sector’s best-ever year is less than one pharma company’s annual R&D budget.

And $8.5 billion across 331 deals means an average of ~$25 million per company, enough for early-stage work but not for the systematic, multi-organ, safety-obsessed clinical programs LEV actually requires.

Cellular reprogramming attracted $1.62 billion, longevity discovery platforms drew $2.65 billion. The US accounts for 57% of longevity companies and 84% of total deal volume.

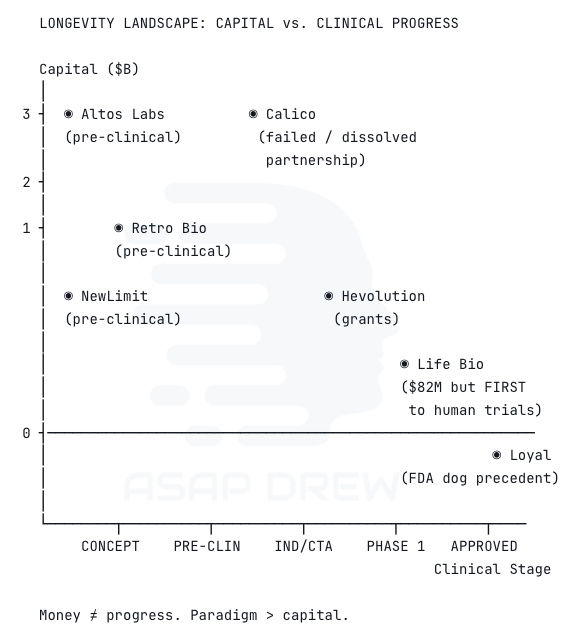

Major players, ranked by capital deployed:

Altos Labs ($3B). The biggest single bet in the space. Backed by Bezos and Milner, employing Nobel laureate Shinya Yamanaka and a deep bench of reprogramming researchers. Still pre-clinical. No public timelines to human trials.

Calico ($3.5B spent). Google’s longevity moonshot, and probably the most expensive failure in the field’s history. AbbVie ended their 11-year partnership in 2025 with remarkably little clinical progress. Pursued healthspan interventions rather than true age reversal. A cautionary tale about what happens when you spend billions without the right paradigm.

Retro Biosciences (~$1B+ raised, ~$5B valuation). Backed by Sam Altman. Pursuing reprogramming, autophagy, and plasma therapeutics with the stated goal of extending human lifespan by 10 years. Moving fast but still pre-clinical on the reprogramming side.

NewLimit ($1.62B valuation). Co-founded by Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong. Epigenetic reprogramming focus. Eli Lilly’s venture arm investing is a signal that mainstream pharma is starting to take this seriously.

Hevolution Foundation ($400M+ committed). Saudi Arabia’s philanthropic funder of aging biology. Largest single philanthropic commitment to the field. Funds both basic research and translational work globally.

Life Biosciences (~$82M raised, but punching way above its weight). Co-founded by David Sinclair. Fewer than 20 employees. Despite being dramatically smaller than Altos or Calico, they’re the ones who actually got FDA IND clearance first. Received clearance January 28, 2026 for ER-100, delivering OSK factors to retinal cells in patients with open-angle glaucoma and NAION. First time partial epigenetic reprogramming enters human clinical testing. Expects to enroll first patients within months, with results potentially by late 2026 or early 2027.

Unity Biotechnology (dissolved). Raised hundreds of millions for senolytic approaches. Phase 2b trial narrowly missed the primary endpoint. Company dissolved September 2025. Like Calico, they pursued damage-clearing rather than program-reversal.

Loyal (regulatory milestone). Secured FDA support for canine

lifespanhealthspan extension drugs, establishing the first regulatory precedent for longevity as a legitimate drug target. Different species, but the regulatory precedent matters enormously.

The pattern here is telling.

The best-funded companies (Altos, Calico) haven’t produced clinical results.

The company that actually reached human trials first (Life Biosciences) raised a fraction of the capital.

And the most expensive effort in the field’s history (Calico) failed because it was operating in the wrong paradigm.

Money matters, but paradigm matters more.

True age reversal: the epigenetic reprogramming paradigm

Partial epigenetic reprogramming is the only demonstrated modality that addresses the informational substrate of aging rather than individual downstream damage pathways. It doesn’t slow aging or clear accumulated damage. It reverses the program itself, resetting cells to a younger epigenetic state while retaining their differentiated identity.

The strongest evidence comes from the 2024 Cano Macip et al. study.

They delivered AAV-encoded inducible OSK factors to 124-week-old wild-type mice (equivalent to roughly 77+ human years) and extended median remaining lifespan by 109% while improving frailty scores. This used a translatable gene therapy vector, not transgenic tricks. No other intervention in the history of aging research has come close to this magnitude in wild-type mice.

But caveats matter. The study was conducted by Rejuvenate Bio, a company with financial interest in the outcome. Sample sizes were small. The 109% figure is remaining lifespan from a very old age, not total lifespan. The result has not been independently replicated.

Safer approaches are emerging. Shift Bioscience’s 2025 preprint reported SB000, a single-factor intervention achieving cellular rejuvenation comparable to full OSKM without inducing pluripotency, directly addressing the cancer risk. The progression from full OSKM (high cancer risk) to cyclic OSKM to OSK minus c-MYC to single-factor represents a clear engineering trajectory toward safe, controllable reprogramming.

Life Biosciences’ Phase 1 trial of ER-100 will deliver OSK locally to the eye, a contained, monitorable target. CSO Sharon Rosenzweig-Lipson has stated the trial’s primary goal is demonstrating safe delivery, with any visual improvement signals being “highly encouraging” bonuses. This is not a systemic aging reversal trial. It’s a safety trial in one organ. The distance from “safe OSK delivery to retinal cells” to “safe whole-body epigenetic reset” is measured in decades, not years.

Key unknowns that remain genuinely unsettled:

The cancer risk of long-term reprogramming factor expression in humans is unknown and may only manifest over years or decades.

Nobody has demonstrated systemic whole-body reprogramming that reaches all tissues.

Current AAV delivery sends roughly 80% of payload to the liver, and the blood-brain barrier remains difficult to cross.

Pre-existing immunity to AAV vectors affects 30–60% of humans.

The mouse-to-human translation rate in drug development is around 10% (roughly 90% clinical trial failure rate). Expecting proportional human translation of the mouse result would be naive.

Note from Human: These are mostly defeatist cop-outs. Cancer risk for elderly is irrelevant if it’s not immediate because the counterfactual is death. Delivery methods should be mostly a non-issue by the mid 2030s. The “mouse translation” nonsense can be avoided entirely by experimenting directly on humans.

Adjacent fields that could accelerate (or complicate) the picture

Bioelectric signaling and morphoceuticals

Michael Levin’s group at Tufts has developed a complementary framework viewing aging as a loss of morphostatic information: the degradation of bioelectric prepatterns that maintain tissue and organ architecture. Published in Ageing Research Reviews (2024), Pio-Lopez and Levin propose that endogenous bioelectric signaling, which coordinates cells into functional multicellular structures, progressively breaks down with age. If aging is partly a failure of the body’s bioelectric “software” and not just molecular damage or epigenetic drift, then interventions at the bioelectric level could offer a complementary or even orthogonal attack vector.

Morphoceuticals Inc., co-founded by Levin, is building a bioelectrome atlas using AI and multiomics to map the body’s voltage patterns and identify druggable ion channel targets. Their earlier work demonstrated functional limb regeneration in frogs through brief exposure to ion channel-modulating cocktails, and they’re now testing in rodent models. Levin’s 2025 work on bioelectric patterns in immortal vs. mortal hydra provides direct evidence linking bioelectric state maintenance to organismal aging. Astonishing Labs, another Levin co-founded startup, is specifically focused on aging applications. Levin has also begun collaborating with David Sinclair to investigate whether bioelectric and epigenetic reprogramming approaches might be synergistic.

Why this matters for LEV: if aging is multi-causal, involving epigenetic drift AND bioelectric degradation AND hallmark damage cascading, then reprogramming alone may be insufficient. You might reset the epigenome but leave the morphostatic patterns degraded, leading to rapid re-aging. Conversely, if bioelectric interventions prove independently capable of meaningful rejuvenation using small molecules rather than gene therapy, they could be faster to develop and deploy. This is speculative but scientifically grounded, and it represents a genuine second front that most longevity analysis completely ignores.

Why cautious skepticism is warranted: Levin’s work is primarily in planaria, frogs, and hydra. Mammalian bioelectric aging research is in its infancy. Morphoceuticals is pre-clinical with no clear timeline to human trials. The field lacks the clean, dramatic results that reprogramming can point to. The theoretical framework is compelling but the translational gap is enormous.

Chemical reprogramming

Small-molecule cocktails for cellular reprogramming are being developed as an alternative to gene therapy delivery of transcription factors.

A 2025 review notes that chemical cocktails have achieved full iPSC reprogramming in vitro, reversed senescence in human fibroblasts, and extended lifespan in C. elegans. If these can work for partial reprogramming in mammals, they bypass the gene therapy delivery bottleneck entirely, a potentially massive acceleration. But this remains early-stage, and the specificity challenges of small molecules in a whole-organism context are severe.

Bridge therapies: the case for skepticism

Everything else in the longevity toolkit operates within a fundamentally different paradigm.

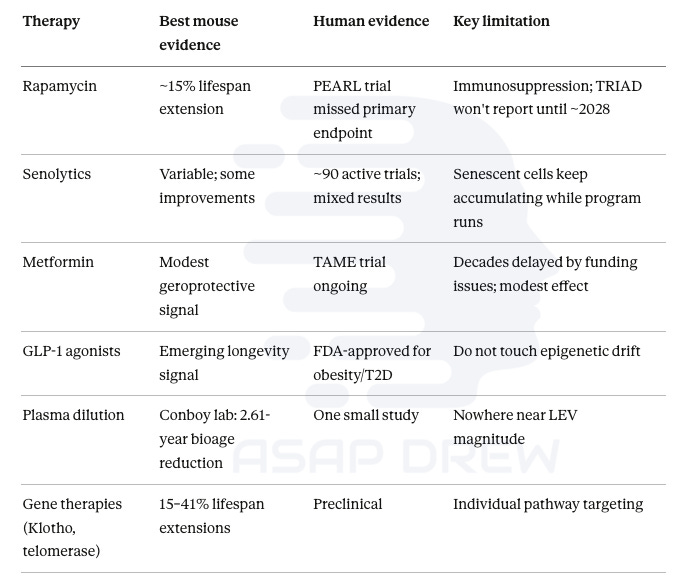

Rapamycin, senolytics, metformin, GLP-1 agonists, NAD+ precursors, plasma dilution: these modulate individual damage pathways or slow accumulation. They don’t reset the underlying program. Their ceiling is single-digit years of life extension, and the evidence that they meaningfully extend life in healthy humans is weak to nonexistent.

Rapamycin is the most validated geroprotective across species at roughly 15% mouse lifespan extension, but the PEARL human trial missed its primary endpoint, and the Dog Aging Project’s TRIAD trial won’t report until about 2028.

Senolytics have around 90 active clinical trials with mixed results; the fundamental problem is that senescent cells keep accumulating because the aging program is still running. Clearing debris without stopping the source.

Metformin’s TAME trial was delayed a decade by funding issues; a positive result matters mainly because it would establish aging as an FDA-recognized therapeutic target, not because metformin itself will achieve LEV.

GLP-1 agonists show promising anti-cancer, cardioprotective, and neuroprotective effects but don’t touch epigenetic drift.

Plasma dilution showed 2.61 years of biological age reduction in one small study.

Single-gene therapies targeting Klotho, telomerase, or follistatin have shown 15–41% mouse lifespan extensions but address individual pathways rather than the master program.

The healthy user bias problem is underappreciated.

The people most likely to adopt bridge therapies are the same ones who exercise, eat well, manage stress, maintain social connections, and have good genetics. Attributing longevity outcomes to the therapy rather than the comprehensive health optimization profile of the user is a classic confound. For someone already in excellent health with favorable genetics, it’s not obvious that stacking rapamycin or metformin on top does anything meaningful. These compounds may primarily bring unhealthy people closer to the baseline that healthy people already occupy, rather than pushing healthy people past it.

Bridge therapies could also backfire. Immunosuppression from rapamycin carries real infection risk. Long-term senolytic use could disrupt signaling roles senescent cells play in wound healing and tumor suppression. Metformin may blunt exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptation. For someone with genuinely good genetics and health practices, the risk-benefit calculus is ambiguous at best.

The only honest argument for bridge therapies in the LEV context is that they may reduce the probability of early biological death from a specific cause (heart attack, cancer caught late) before true age reversal arrives. Essentially buying lottery tickets against premature exits. That’s a valid argument but much more modest than the “bridge to LEV” rhetoric implies.

AI and drug discovery: mostly noise, one signal worth watching

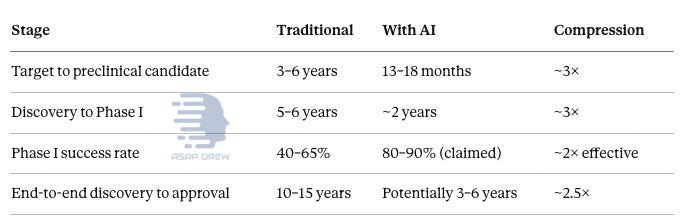

AI is unquestionably compressing early-stage drug discovery timelines. Insilico Medicine took an AI-designed drug from target identification to Phase I in under 30 months at $2.6 million versus the industry standard of 6+ years and billions. Isomorphic Labs (DeepMind’s spinoff) signed $3 billion in partnerships with Eli Lilly and Novartis. Over 75 AI-derived molecules reached clinical stages by end of 2024.

But I’ll be direct: none of this is particularly novel, and none of it is specifically relevant to aging in the way that matters for LEV. AI drug discovery compresses timelines for conventional drug development: finding better molecules faster for known targets. That’s useful for developing better senolytics, better mTOR modulators, better GLP-1 analogs. It doesn’t change the fundamental paradigm. It makes the sandbagging approach faster. Not the dam repair.

Target-to-preclinical-candidate timelines have shrunk from 3–6 years to 13–18 months, roughly 3× compression. Discovery-to-Phase-I similarly compresses to about 2 years. Phase I success rates are claimed to roughly double. End-to-end discovery-to-approval could potentially compress from 10–15 years to 3–6 years. But no AI-generated drug has received full regulatory approval yet.

The one scenario where AI becomes truly transformative for aging is closed-loop, autonomous laboratories specifically designed and exclusively focused on aging biology.

Systems that can design reprogramming protocols, test them in organoids or model organisms, measure biological age in real-time, iterate, and run thousands of experiments per week with zero human bottleneck. That would be qualitatively different from “AI finds drug candidates faster.” It would be AI as the principal investigator of aging, not just a tool for human scientists. Nothing like this exists in meaningful form yet, though companies like Recursion Pharmaceuticals (processing 2.2 million samples/week in automated labs) represent early steps.

The most realistic overall estimate is that AI compresses the drug pipeline by 2–3×. A 15-year development cycle becomes 5–7 years. Useful but not paradigm-shifting unless the entire research infrastructure pivots toward closed-loop aging experimentation. That hasn’t happened and there’s no indication it will soon.

The measurement problem

Epigenetic clocks are both the field’s greatest advance and a genuine bottleneck.

DunedinPACE, GrimAge, and Gladyshev’s 2024 causality-enriched clocks (DamAge and AdaptAge) represent real progress. Several interventions have demonstrated measurable epigenetic age reversal in humans: the TRIIM trial (2.5 years), a diet/lifestyle RCT (3.23 years in 8 weeks), plasma exchange (2.61 years).

The fundamental problem is that no study has demonstrated that reversing an epigenetic clock reading actually extends human lifespan. The FDA doesn’t accept epigenetic clocks as validated clinical endpoints.

A 2025 npj Aging paper raised the question of whether we actually need aging clocks at all, highlighting inconsistent validation and ignored prediction uncertainty.

Biological age is fluid, spiking during surgery, pregnancy, and illness, then recovering. Whether measured “reversal” reflects genuine rejuvenation or temporary fluctuation remains unclear.

Without a validated surrogate endpoint for aging, every clinical trial must use disease-specific outcomes, adding years or decades to development. This bottleneck alone could delay LEV by 5–10 years. The TAME trial matters partly for this reason: if its composite endpoint gains regulatory acceptance, it creates the measurement framework every subsequent aging trial needs.

Human Note: We need benchmarks, but they aren’t necessarily as relevant as people think. If you transform an 80-year-old into someone who looks 30 and feels 30 and if swaths of people are suddenly bringing human lifespan average up to ~100 or ~110 etc. and are healthier than 80-year-olds of the past… we know its working. Like AI benchmarks, you don’t need perfection to make progress. The proof is looks, objective function, subjective feel, and terminal upper bounds. Measurements help but aren’t fully necessary. Measuring after reversal interventions might even be more helpful (reverse engineer what changed and what’s the strongest signal).

Six bottlenecks

Regulatory paralysis. The FDA doesn’t classify aging as a disease. Every longevity therapy must target specific disease indications. Loyal’s dog approvals and TAME’s design are the only cracks in this wall. This is the kind of institutional barrier that can persist for decades even after the science is settled.

Delivery technology. Systemic IV injection sends roughly 80% of payload to the liver. The blood-brain barrier remains tough to cross. Pre-existing AAV immunity affects 30–60% of humans. No technology achieves whole-body distribution at therapeutic doses. Engineered capsids, LNP-DNA hybrids, and exosome-based delivery are all in development but this is the hardest engineering challenge in the stack.

Cancer risk from reprogramming. The OSKM-to-single-factor trajectory is improving, but long-term cancer risk in humans is unknown. A single cancer death in an early trial could set the field back years or decades.

Mouse-to-human translation. Drug development has a roughly 90% clinical trial failure rate. Alzheimer’s research saw dozens of mouse-effective drugs fail in humans. The 109% mouse result is extraordinary; proportional human translation would be naive to expect.

The measurement gap. Without validated aging biomarkers as clinical endpoints, trials take much longer and cost much more than necessary.

The hallmark interconnection problem. Aging’s 12+ hallmarks are deeply intertwined. Addressing one may shift mortality burden to another. The bioelectric evidence suggests an additional dimension (tissue-level architectural maintenance) that reprogramming alone may not address.

All six are engineering and institutional problems, not fundamental scientific barriers. But “engineering problem” doesn’t mean easy or fast. Gene therapy delivery has been an engineering problem since the early 2000s and still isn’t fully solved for most tissues. Regulatory reform is a political problem that has resisted change for decades.

What the optimists and skeptics get right and wrong

The optimists

Ray Kurzweil predicts LEV by 2029–2032.

Aubrey de Grey maintains 50% by the late 2030s.

David Sinclair predicts an age-reversing pill by ~2035.

Peter Diamandis echoes the ~2030 timeline.

They’re right that aging is a biological process amenable to intervention, that epigenetic reprogramming is the breakthrough approach, and that the field is massively underfunded.

They’re wrong on timelines. De Grey’s original 2004 prediction of LEV by ~2029 will be wrong. Kurzweil’s prediction requires biological simulators enabling in silico trials by the late 2020s, and there’s no evidence this will happen. De Grey’s LEV Foundation mouse rejuvenation study achieved only 4 months of extension versus their 12-month goal.

These optimists systematically underweight translation risk, regulatory friction, delivery challenges, and most importantly the political economy that determines whether resources are actually deployed. They treat the problem as if the only variable is science, when the binding constraint is institutional will.

The skeptics

Jay Olshansky’s 2024 Nature Aging paper demonstrated that life expectancy improvements are decelerating across the world’s longest-lived populations. He’s argued that “most people alive today at older ages are living on time manufactured by medicine” and that “these medical Band-Aids are producing fewer years of life even though they’re occurring at an accelerated pace.”

His characterization of this as a “glass ceiling, not a brick wall” is apt. He’s not saying radical life extension is impossible; he’s saying it requires going after aging itself, and we haven’t.

They’re right that incremental life expectancy deceleration is real and well-documented, that previous “breakthroughs” like resveratrol and HGH failed, that the mouse-to-human translation rate is terrible, and that Calico’s $3.5 billion failure is sobering.

They’re wrong to extrapolate from incremental approaches to the impossibility of transformative ones. Partial reprogramming is qualitatively different from rapamycin or caloric restriction; it addresses the program, not individual damage pathways.

Olshansky’s analysis is correct for the paradigm of slowing aging and treating diseases. It doesn’t apply to the paradigm of reversing the aging program itself.

But the skeptics are right that the transformative paradigm remains unproven in humans, and the gap between “concept works in aged mice” and “works safely in humans at scale” is genuinely unknown.

Prediction markets

Metaculus hosts several relevant questions with meaningfully different forecasts:

Q6592, the main LEV question (”when will a country reach sustained 1 year/year life expectancy increase?”), sits at a community median of July 2057 from 143 forecasters.

Q5852, which asks the softer question of when biological lifespans will increase by at least 0.75 years per year, has a community median of February 2066 from 68 forecasters, with the upper 75th percentile out at December 2103 and a 13.4% probability assigned to “never.”

Q353 asks whether anyone born before 2001 will live to 150, currently at roughly 55% yes.

Q1628 forecasts the longest verified human lifespan by January 1, 2050 at only 126 years.

The picture these paint is more pessimistic than you’d expect if you only read longevity Twitter. The community thinks strict LEV arrives around 2057, but even the softer 0.75x target doesn’t arrive until 2066, and more than one in eight forecasters think the softer target never arrives. The “someone lives to 150” question being at only 55% is notable; if LEV were widely expected by mid-century, that number should be much higher. And forecasting the longest verified lifespan at just 126 by 2050 suggests the community expects very modest progress over the next 25 years.

These markets probably underweight the resource allocation variable since they’re forecasting current trajectory, not optimal allocation. But as I’ve argued, optimal allocation probably isn’t coming.

Probability distribution

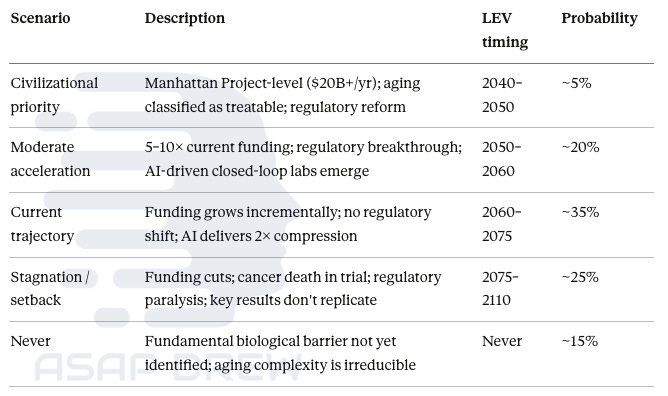

These are my probabilities, not market aggregates. I’ve tried to think carefully about the political economy constraints, genuine scientific uncertainty, and the gap between what’s technically achievable and what will actually be pursued.

I give the civilizational priority scenario only 5% because there’s no political mechanism that would produce $20+ billion/year commitment. Moderate acceleration at 5–10× current funding with a regulatory breakthrough and emergence of AI-driven closed-loop labs gets 20%. Current trajectory, where funding grows incrementally and nothing structurally changes, is the most likely single scenario at 35%. Stagnation or setback from funding cuts, a cancer death in a reprogramming trial, or failure to replicate key results gets 25%. And 15% for “never” because there may be fundamental barriers we haven’t identified, or the hallmark interconnection and bioelectric degradation problems could create a ceiling no single paradigm breaks through.

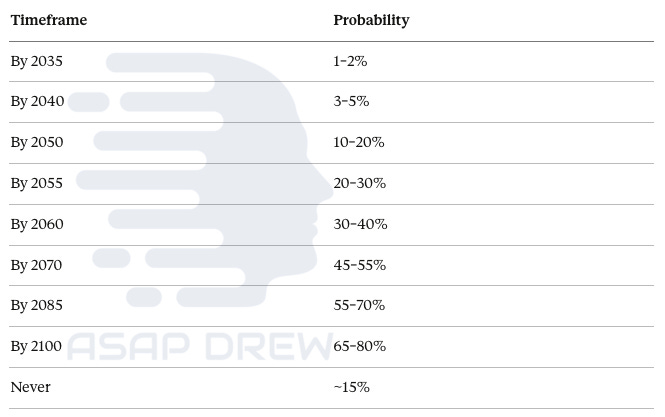

Cumulative:

By 2035 we’re at essentially negligible probability since we’re just entering Phase 1 human trials for a single-organ application. By 2050, 10–20%, possible only if moderate acceleration or civilizational priority scenarios materialize, which I think is unlikely. By 2060, 30–40%. By 2085, 55–70%. Residual “never” of about 15% reflects genuine uncertainty about whether aging is the kind of problem that admits of a total solution.

Median: ~2065 for the first cohort, wealthy and health-optimized individuals in developed nations with access to combination therapies. Broader population access 10–15 years later.

These are significantly more conservative than v1 of this report (~45% by 2050, median ~2055).

Claude’s revision reflects three things: (1) the political economy problem is more severe than technologists assume, with no mechanism for the resource shift the field needs; (2) bridge therapies are less useful than argued, especially for those with good baseline health; and (3) the Metaculus community itself, despite being a generally tech-optimistic crowd, places strict LEV at 2057 and softer LEV at 2066 with a meaningful “never” tail. I’m roughly in line with their community estimates, maybe slightly more pessimistic because I weight the political economy constraints more heavily than I think the average Metaculus forecaster does.

Bottom line

The question “Will humans achieve LEV?” is not settled despite what the optimists claim. The 109% mouse result is extraordinary but unreplicated, from a single lab with financial interest, using a modality never tested systemically in humans.

The first human trial is a local safety study in the eye. The gap between “it works in aged mice” and “it works safely in humans at scale” is the gap that has destroyed countless promising therapies throughout the history of medicine.

“When?” reduces primarily to:

Will civilization actually try?

The world spends more treating Alzheimer’s alone than it has ever spent on the upstream cause of Alzheimer’s, cancer, heart disease, and every other age-related pathology combined. That’s not rational but it is stable. The institutional forces producing this allocation aren’t weakening. Private capital and billionaire philanthropy are pushing things forward but they aren’t substitutes for coordinated civilizational effort.

The science is real. The adjacent fields (bioelectric signaling, chemical reprogramming, precision delivery) offer genuine complementary avenues. The ROI case is obvious. But the timeline is not primarily a function of scientific possibility. It’s a function of political will that doesn’t exist, institutional reform nobody is pursuing, and resource allocation that favors treating symptoms over curing causes by roughly 200:1.

For someone aged 40 in excellent health today, the honest probability of personally reaching LEV is roughly 15–25%, contingent on a resource allocation shift that hasn’t happened and that I see no clear mechanism to produce. That rises to 30–40% under moderate acceleration but falls to single digits under stagnation.

100,000 people die of age-related causes every day. The engineering path from mouse proof-of-concept to human application is visible.

What’s missing isn’t knowledge, technology, or talent.

What’s missing is the collective decision to treat this as the civilizational priority it obviously is, and there’s no reason to believe that decision is coming soon.

Since the U.S. doesn’t seem to be interested… I’ve said that China, UAE (or a Gulf State conglomerate), Singapore, or Mossad (Israel) should just get the show on the road.

Most people would love to see this happen. Low fertility rates and the looming human capital crisis won’t be pretty if we don’t do some of the following: upgrade biology and/or reverse biological aging (LEV) and/or diffuse AGI/ASI digitally and robotically.

We should be Operation Warp Speeding Biological Aging ASAP.