Do Women Without Kids Regret It? Happiness, Loneliness, Data in Childfree Adults

Many women with kids love sadistically dunking on childfree women... but they may be surprised to learn that the childless women are doing alright!

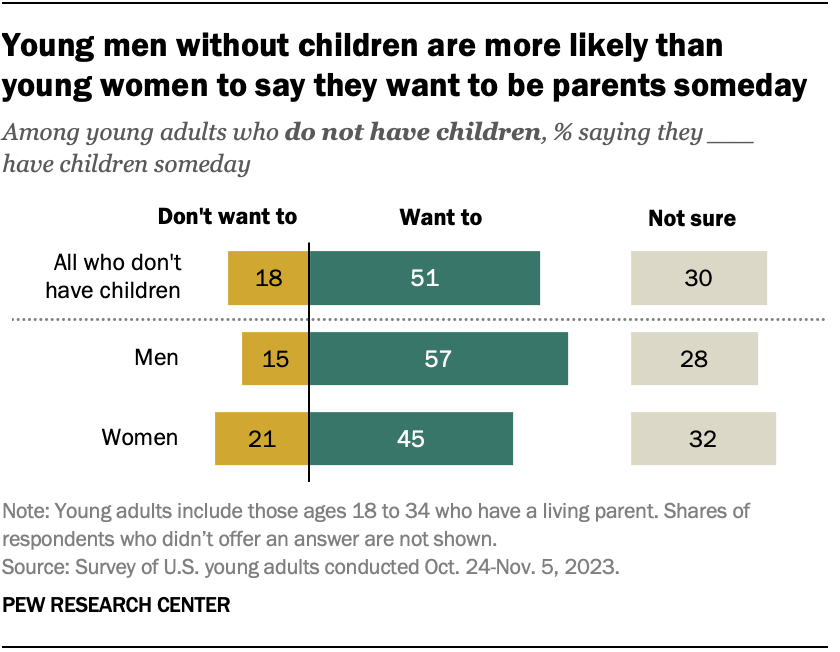

In the younger generation, there are now more childfree women who don’t want kids than childfree men who don’t want kids. (This is is a statistical rarity… has never been observed before in U.S. history.) (Big difference between Gen-Z and Boomers)

And from what I’ve observed, many people take pleasure in dunking on women without kids… especially right-wingers (i.e. Conservatives). They often sadistically predict some sort of eternal life of loneliness or unhappiness that involves some combination of:

Copious amounts of wine

SSRIs and therapy bills

1000 cats and a few pitbulls

Volunteering at NGOs to help African migrants

I think the reason for this projection has to do with the fact that many men and women with kids:

Can’t imagine life without kids (they really wanted them and are happier with them).

Can’t comprehend why women without kids may not want kids (e.g. genetic disorders, mental disorders, financial struggles, etc.)… many who are mentally stable and healthy don’t understand what others are experiencing and think everyone is like them.

Don’t understand that many women without kids have extremely satisfying lives without kids (they refuse to believe it).

Are upset that racial/ethnic demographics of the U.S. are changing rapidly (gradually lower IQ, fewer whites, more racial tribalism, etc.) and fewer White kids will be around to be friends with their White kids.

Are upset at misdirected empathy (NGOs, illegals, infinity migration, voting ultra-left-wing against the ethos of the U.S. for things like socialism/communism, anti-merit/pro-DEI, etc.).

Are upset about the low birth rates and think this could drastically degrade quality of life in the future of the U.S. (a reasonable concern).

Think that women without kids are going against God or whatever (I think this is the least common reason for the anger). But the argument is something like: It is your duty to reject pointless hedonism… Take responsibility, and procreate!

Essentially many women and men with kids are hoping to guilt trip childless people into having kids. But why? It reinforces their logic that they made the “right decision” to have kids (power in numbers).

I also think that they are genuinely concerned about the future of the U.S. In the past, the U.S. was mostly Whites that had a lot of things in common and they mostly assimilated well, worked hard, etc.

They don’t want to say this second part publicly because they seem “racist” or whatever. But let’s do a thought experiment for a second:

Blue Aliens populate Planet A: The planet is productive, healthy, mostly homogenous with low crime rates, low corruption, minimal dysfunction, etc. but extremely low birth rates.

Orange Aliens populate Planet B: The planet is not very productive, has some health issues, high crime rates, high corruption, a lot of dysfunction, etc. but high birth rates in part due to the Blue Aliens sending interplanetary aid (they wouldn’t survive as much without it).

The Blues just don’t want to breed much anymore and they need workers so they start bringing Orange Aliens to their planet to “integrate”. Since it’s a democracy, the Orange Aliens get to vote and they start voting for policies that only benefit the Orange… and they insert as many Orange in political positions to gain influence. A subset of the Blues feel bad for them (the empathy that would’ve been channeled to kids if they had them… now goes toward the “marginalized” Orange).

The policies the Orange Aliens like? Minimal law enforcement (because they commit more crime and feel discriminated against when arrested at higher rates than the law abiding Blues), Socialism & Handouts (they don’t understand economics but it allows them to extract more than they contribute), and Anti-Blue policies (they view the Blues as assholes).

The parents of Blues do what they can to try to convince fellow Blues to have more kids and reverse this trend… they don’t want the entire planet to be ruined by lower IQ Oranges and the dysfunction that they bring. They want their kids to grow up in a world like they had (low crime, low corruption, prosperity)… but things are headed in the wrong direction.

They try to guilt trip other Blues to have more kids by posting on social media… but it doesn’t work. I think this is kind of like where we are right now in the U.S. and certain parts of Europe. Some would argue that both the U.S. and E.U. are “too far gone” (no putting the cat back in the bag)… and they might be right.

If you are remotely aware of evolved trait distributions and behavioral genetics in modern populations, allowing unfiltered illegal immigration (and protecting illegals and fast-tracking citizenship or giving their kids auto-citizenship via birthright naturalization so they get votes is a self-inflicted Trojan Horse).

I think this is the logic and why we see (mostly Whites with kids) angry about the low birth rates in U.S. and E.U. This is why Elon is upset… Whites with kids want other people with similar traits/values (intelligence, prosociality, trusting, anti-clannishness, etc.) as them to share the future with… not a bunch of cultural clashes between markedly different races/ethnicities.

Note #1: This is a hypothesis: An immigration policy selecting only for IQ (above a certain threshold) in the U.S. would probably work fairly well to maintain social cohesion, but certain groups still have higher than average clannishness which is a valid concern in democratic politics (higher in-group racial/ethnic bias).

Note #2: There are ways to fix low birth rates intelligently (i.e. maximizing smart/healthy babies)… but I don’t think people have the stomach to implement these policies (e.g. payments to healthy/wealthy to have more kids, free caretakers for healthy/high IQ people having kids, government coercion in countries with low freedom e.g. mandates to give government DNA for “government babies” via paid surrogates.)

Note #3: The way I see things in the future is likely some combination of: (1) AI/robotics (can be more efficient with fewer, higher IQ people); (2) IQ/brain upgrades for everyone (will help eliminate a lot of antisociality, making it much easier to live with other groups); (3) survivorship effect: traits that enable reproduction in spite of modern living pressures move forward and may contribute to a rebound in births after they plummet.

Are Childless Women Really Doomed to Regret Not Having Kids?

Most of us have heard some version of this warning:

“If you don’t have kids, you’ll regret it. You’ll end up lonely and depressed in old age.”

It’s usually aimed at women. Men mostly get to skate by: childless men are barely even a stereotype.

But when you look at the research on mental health, life satisfaction, and loneliness, a different picture shows up:

Many women are childless partly because they were already anxious, depressed, unwell, or unsure, not suddenly unhappy years later.

Voluntarily childfree women, as a group, do not show massive secret regret in late life.

Parents are not a blissfully regret‑free control group; a small but real minority regret having children.

The people who seem most at risk of deep isolation as low‑fertility societies age are often men without partners and kids.

Let’s walk through the evidence and the complex psychology behind it.

1. Who actually doesn’t want kids — and why?

Childfree adults are not a tiny fringe.

A series of representative surveys in Michigan found that around 21–26% of adults identify as childfree—they don’t have children and don’t want them in future. (PLOS)

A 2024 follow‑up showed the share of childfree adults increased after the Dobbs decision tightened abortion access, suggesting some adults react to risk and instability by deciding they don’t want children at all. (PLOS)

National U.S. polling by Pew shows that among adults under 50 who don’t expect to have kids, the top reason, by far, is “I just don’t want children.” Environmental and financial concerns come behind that. (Pew)

So we’re not talking about a few bitter outliers. In many places, “I don’t want kids” is a normal, stable identity.

Those reasons are often layered:

Mental health & genetics – Fear of passing on depression, bipolar, psychosis, or other conditions; fear of being an unstable or unsafe parent. (Nature)

Material reality – Housing costs, precarious work, expensive childcare, and weak social supports make parenthood feel like a financial trap. (The Guardian)

Macro anxiety – Climate change is a genuine deterrent for a noticeable minority, especially younger women. (AP News) (This should NOT be a thing… yes climate change from man and cyclicality are real… but it’s not even necessarily a bad thing! People have been brainwashed! It’s an extremely solvable issue if actually necessary!)

All of that sits on top of temperament and values. Some people just don’t feel a pull toward the parent role, even if everything else were perfect.

Note: Many average and above average IQ people refrain from having kids in part because they are able to think critically about the future. Lower IQ people do not really “think” or “plan” or have much conception of the future… present-moment-centrism is what matters… and thus have kids without thinking through the consequences. Someone with mental illness and average/above average IQ may think they are simply being responsible not having kids (e.g. a kid may inherit some anxiety, depression, personality trait, etc. that makes life more difficult.)

Note: Another major reason is people have become particularly “choosy” dating. Both men and women (but especially women) want to date someone out of their “league” (appearance, education/cognitive status, financial status, etc.). This combo of wanting to “reach up,” taking their time for Mr./Mrs. Perfect, and the entire Paradox of Choice results in lower marriage/birth rates.

2. Mental health vs. childlessness: causality runs both ways

The stereotype sounds like:

No kids → you get depressed and lonely.

But big population studies show an important reverse effect:

Depression, anxiety and other illnesses → you’re less likely to have kids in the first place.

A) Psychiatric disorders predict lower odds of becoming a parent

Large registry studies in Northern Europe are especially clear:

A 2025 Finnish study of young adults (born 1980–1995) found that almost all major mental disorders were linked to a lower likelihood of having a first child, for both men and women. (Obstetrics & Gynecology)

A nationwide Finnish register study of more than 1.4 million people found that secondary‑care–treated depression was associated with lower odds of having children and fewer total children, for both sexes. (ScienceDirect)

Another study combining Finnish and Swedish data found that a wide range of diseases—not just psychiatric ones—were associated with lifelong childlessness, partly by reducing partnership formation and partly by direct health effects; mental and behavioural disorders showed some of the strongest links. (Nature)

These are not subtle effects: one 2024 Finnish analysis estimated that depression reduced the annual probability of having a child by around 2–3 percentage points for women (and somewhat more for men) in early adulthood. (ScienceDirect)

So when you look at “people without children” as a group, you’re already looking at:

more people with chronic mental health conditions,

more people with serious physical illness,

more people who struggled to form or maintain partnerships.

That’s a selection effect, and it matters a lot for how we interpret later-life outcomes.

B) Conscious mental‑health‑based reasons for not having kids

On top of the statistical pattern, qualitative work with people who have serious mental illness, trauma histories, or chronic instability finds recurring themes (Nature):

Fear of harming a child (“What if I relapse, or can’t be emotionally present?”)

Fear of passing on genes (“I don’t want my child to inherit my condition.”)

Self‑knowledge of limits (“I can barely manage myself—adding a baby would break me.”)

So in a very real sense, for many:

They are not childless and therefore depressed; they are depressed or unwell and therefore childless.

That doesn’t cover everyone, but it sharply complicates the simple “no kids → misery” story.

3. Do kids actually make people happier?

This is where things get messy, because:

People justify their choices (parents and non‑parents alike), and

Happiness is influenced by a ton of things besides kids.

So researchers lean on longitudinal data: tracking the same people before and after they have children.

A) “Does the stork deliver happiness?”

A famous analysis using the German Socio‑Economic Panel (SOEP) tackled exactly this question:

The paper “Does the Stork Deliver Happiness?” followed women over time and looked at life satisfaction around the birth of children.

It found small, short‑lived increases in happiness around the time of birth, especially for the first child, but no large, sustained boost in long‑term life satisfaction once you account for how happy women were before motherhood.

Another analysis titled “Happy People Have Children” used the same panel to show that happier adults are more likely to go on to have children, suggesting that part of the “parents are happier” pattern is just happy people self‑selecting into parenthood.

B) Later-life satisfaction: parents vs non‑parents

For older adults, the picture is similarly mixed:

A 2025 cross‑national study of people 60+ found that parents sometimes report slightly higher life satisfaction than non‑parents, but the differences were small and varied a lot by country. Welfare states with strong social supports showed weaker or no advantages for parents. (PMC)

A large meta‑analysis of Asian datasets (China, Korea, India) versus Western samples found that childlessness was more strongly linked to depressive symptoms in some Asian settings—likely because norms and family structures differ. (BioMed)

The takeaway isn’t “kids make you unhappy” or “kids make you ecstatic” so much as:

Kids change your happiness profile: more highs, more lows, more stress, more meaning — but long‑term averages often drift back toward your baseline and are heavily shaped by relationship quality, money, and policy support.

4. Regret and rationalization: both paths use the same psychology

Whether you have kids or not, people rarely say “I made an irreversible mistake.” They rationalize.

That’s just cognitive dissonance 101: once a choice is irreversible, we adjust the story we tell ourselves to live with it.

A) Parents who regret having children

This topic was taboo for a long time, but that’s changing.

Israeli sociologist Orna Donath’s work “Regretting Motherhood” used in‑depth interviews with 23 mothers who explicitly say they regret becoming mothers, even though they love their children; she situates these experiences within a strongly pronatalist culture that insists motherhood is every woman’s destiny. (Chicago Journals)

Quantitative work by Konrad Piotrowski in Poland used large national samples and a “parenthood regret” scale. His 2021 PLOS ONE paper found that roughly 7–14% of parents in two samples scored as regretting parenthood, and regret was strongly linked to poorer mental and physical health, financial stress, and parental burnout. (PubMed)

A 2023 summary of the emerging literature estimated that in wealthy countries, around 5–14% of parents may regret having children, with higher estimates in some Polish samples. (Psychology Today)

UK polling by YouGov found that 8% of parents directly said they regret having children, and another 6% said they had previously regretted it but no longer do. (YouGov)

A recurring pattern in both qualitative and quantitative work is that regret is often wrapped up with context:

unplanned or pressured pregnancies,

poor or abusive relationships,

financial hardship or lack of support,

children with very high care needs in under‑resourced systems.

In other words, a lot of “I regret having kids” is also:

“I regret having kids with this partner, at this time, under these conditions.”

So blaming “parenthood itself” for all of that pain is a bit like blaming “marriage” for the misery of a specific bad relationship.

B) People who regret not having kids

Regret runs the other way too—but, again, the nuance matters.

For women:

A classic study of 72 middle‑aged and older women compared voluntarily childless, involuntarily childless, and mothers. Voluntarily childless women had higher overall wellbeing, more autonomy, and less child‑related regret than involuntarily childless women, and their wellbeing was comparable to mothers. (PubMed)

Qualitative studies of older childless women find a wide spread:

some are deeply satisfied and say they would choose the same life again,

some feel a persistent grief about the children they couldn’t have,

many sit in a “both/and” space—content overall but with occasional pangs. (PMC)

Importantly, research and reviews keep coming back to the same pattern:

Voluntary childlessness in women is not associated with high rates of crushing regret.

Involuntary childlessness and strong unfulfilled motherhood ideals are where the heaviest suffering sits. (PubMed)

Do some voluntarily childfree people talk themselves into feeling great about a choice they’re ambivalent about? Absolutely. But the data just do not support the idea that there’s a huge hidden population of childfree women whose lives are dominated by silent regret.

5. The “massive void” and loneliness question

This is the emotional core of the scare stories:

“Without kids, you’ll have a huge hole in your life and die lonely.”

So what do we actually see?

A) Does childlessness predict loneliness and depression in old age?

Some of the oldest work on this is surprisingly reassuring:

A 1998 U.S. study of older adults found that childlessness was not significantly associated with greater loneliness or depression once you accounted for marital status and health. Parents and childless elders showed similar wellbeing when other factors were held constant. (PubMed)

A Swedish study using national registers found that childless older adults did not report more loneliness or lower meaning in life than parents, though they sometimes had slightly lower life satisfaction on average. (ResearchGate)

A 2011 study of Swedish men and women 85+ likewise reported broadly similar psychological wellbeing between parents and the childless after adjusting for marital status and health, though childless elders had smaller family networks. (BioMed)

More recent work continues the theme:

A 2025 U.S. study estimated that about 17% of adults 55+ are childless, and most studies find no or only small mental‑health differences between them and parents, particularly once you control for partnership status and socioeconomic conditions. (OUP)

So: childlessness alone is not the curse people assume.

B) Where loneliness does show up: context and gender

Childlessness can matter in combination with other things:

A 2024 Canadian study on social and emotional loneliness found that childlessness was linked to higher social loneliness in middle and later life, but this association was stronger for men than for women. Childless women often had richer non‑family networks that offset the absence of children. (Cambridge)

The 2025 U.S. study of older adults (55+) found that childless men reported more emotional loneliness than fathers, whereas childless women were not notably lonelier than mothers when marital status and health were controlled. Women who had lost all children to death had the worst emotional loneliness of any group. (OUP)

In other words:

Having kids can help some people—especially men—feel less lonely in later life.

But many childless older women are not lonelier than mothers, and childless men are often the ones at greater risk.

C) What about worry about loneliness?

Perceptions matter too:

A 2024 Pew survey of U.S. adults 50+ without children found that 19% said they frequently worry about being lonely when they’re older, and 26% worried a lot about who would care for them; that’s a real concern, but it’s far from “almost all.” (Pew).

There were no big gender differences in loneliness worry, though childless women worried more than men about future caregiving burden.

So yes, fear of future loneliness is part of the childfree calculus—but the evidence doesn’t show that most childless people end up dramatically more lonely than parents, especially if they build other strong ties.

Note: Something to mention is that plenty of people with kids end up very lonely. Kids move away or marry and do their own thing, move across the country, move to a different continent, etc. Some kids don’t keep steady contact with parents because they are “busy” or whatever… so you can still end up very lonely in old age even if you have kids. It’s probably less likely to happen, but still could happen.

6. Gendered social networks: why childless men may be hit hardest

What do the data show? Men are taking the biggest beating. This is why we see high rates of substance abuse, addiction, loneliness and suicides in men.

A) Women’s vs men’s friendship patterns

Social‑network research consistently finds:

Women tend to maintain more emotionally intimate, dyadic friendships and broader networks of support (friends, siblings, neighbours, colleagues). (ScienceDirect)

Men are more likely to:

have fewer close confidants,

rely heavily on a romantic partner for emotional support,

build activity‑based friendships (work, sports, gaming) that may be less emotionally deep. (PMC)

A 2025 research summary from Humboldt University, reviewing multiple studies, concluded that heterosexual men are more dependent on their partners to meet emotional needs than women, who receive more support from family and friends. (Humboldt)

Journalists and psychologists have pointed out that men’s social networks appear to have shrunk over recent decades, leaving them more emotionally dependent on romantic relationships. (Psychology Today)

B) Childless + single + male = high‑risk combination

Now layer childlessness onto that:

The Canadian loneliness study mentioned earlier found that childless men experienced higher levels of social loneliness than childless women, even after accounting for age and other factors. (Cambridge)

A 2011 Swedish study had hypothesized that being unmarried or widowed would combine with childlessness to reduce wellbeing; results suggested that partnership status mattered more than parental status, but childless men without partners were especially vulnerable. (BioMed)

A Gallup/World Poll analysis reported in 2025 found that young American men (15–34) reported higher rates of loneliness than young women, and higher than young men in most other wealthy countries. (WaPo)

Put simply:

A woman without kids is relatively likely to have other strong social ties.

A man without kids and without a partner is relatively likely to have almost no emotionally close relationships.

So as marriage rates drop and fertility falls, the group that may quietly suffer the most isn’t “cat ladies,” but isolated men with thin social networks.

7. Culture, social media, and what we’re “allowed” to feel

It’s impossible to talk about regret and happiness around kids without talking about cultural scripts.

A) Pronatalist pressure and the threat of regret

Donath’s research on regretting motherhood highlights something important: one of pronatalism’s main tools is threatening women with future regret if they don’t have children. (ResearchGate)

Media and family messaging often sound like:

“You’ll change your mind.”

“You’re selfish now, but you’ll regret it later.”

“You’ll die alone if you don’t have kids.”

But they almost never say:

“You might regret having kids you didn’t really want.”

“You might regret doing it with the wrong partner, at the wrong time, with no support.”

Recent reporting and books point out that:

Many women today do “just not want kids” and are tired of being treated as naive, damaged, or incomplete. (WaPo)

There’s an emerging literature and activism making space for mothers who regret having kids and for childfree women who are not secretly broken. (The Guardian)

B) Counter‑narratives: “childfree and thriving”

On the flip side, social media also amplifies childfree triumphalism:

“DINK” (dual‑income‑no‑kids) couples showcasing travel, hobbies, and disposable income.

Forums that highlight the downsides of parenting and frame childfreedom as the only rational choice. (IG)

For someone who is ambivalent, that environment can make it hard to admit:

“I chose not to have kids and mostly like my life… but yes, sometimes I wonder.”

So both parents and non‑parents are swimming in narratives that tell them:

what they should feel,

which feelings are taboo,

which feelings are “on brand” for their identity.

That inevitably shapes survey answers and even people’s private interpretations of their own emotions.

8. Mate choice, timing, and context: regret is rarely about “kids vs no kids” in isolation

A lot of regret is tied up with who people had kids with and when, not just whether they had them.

Research doesn’t give a neat number for “how many people regret the partner, not the kids,” but it does show:

Parental regret is more common among those with financial hardship, poor relationship quality, and children with high care needs. (PubMed)

Many qualitative interviews (and media profiles) capture parents saying, in effect, “I love my children, but I wish I had waited / chosen a different partner / had fewer.” (Atlantic)

On the childless side, regret is often bound up with:

not meeting a suitable partner in time,

health issues,

or structural barriers (cost of living, lack of leave, unstable work). (TIME)

So when people say “I regret having kids” or “I regret not having kids,” very often the regret is about the whole path, not just the presence/absence of children.

That matters, because it means:

You can’t cleanly read “kids vs no kids” as the sole cause of people’s later happiness or misery. The mate, timing, health, money, and culture around that decision are doing a lot of the work.

What can we honestly say, without spin?

Putting all of this together: selection effects, mental health, regret, gender, culture… the most honest summary looks something like this:

Mental and physical health strongly influence who becomes a parent.

Depression, serious mental illness, and chronic disease all reduce the likelihood of having children; some people also consciously avoid parenthood because of these conditions.Voluntarily childfree women are not generally hiding catastrophic regret. They often decided early, report decent or high life satisfaction, and show less child‑related regret than women who wanted kids but couldn’t have them.

Parents are not a regret‑free baseline. Best estimates suggest 5–14% of parents in wealthy countries regret having children, with higher rates in some samples, and these parents show worse mental and physical health.

Childlessness doesn’t automatically mean late‑life loneliness or depression.

Once you control for health, money, and especially marital status, differences in loneliness and wellbeing between parents and non‑parents are often small or non‑existent.Gendered social networks make childless men more vulnerable than childless women. Women are more likely to maintain broad, emotionally rich networks; men rely heavily on partners and, if they have them, kids. Single, childless older men often show more loneliness than almost any other group.

Everyone rationalizes, but that doesn’t erase the patterns. Both parents and non‑parents tell themselves coherent stories to live with irreversible choices. When we factor in good methodology (longitudinal designs, register data, anonymous measures), the remaining signal is still:

Voluntary childlessness, especially for women, is not typically a disaster,

Parenthood is deeply meaningful for many but not a universal happiness upgrade,

And isolated men are a looming social‑health issue we don’t talk about enough.

If the kids vs. childfree decision is personal for you

Just in case this isn’t purely theoretical for you, here’s the grounded, non‑scare‑tactic version:

Current mental health matters. If you’re already stretched thin by anxiety, depression, or trauma, it’s legitimate to weigh that heavily. Many people choose not to have children precisely because they don’t want to pass on suffering or parent from a chronically unstable place. The data suggests that’s a common and understandable choice, not a guaranteed regret.

There is no regret‑free path. Some parents regret, some non‑parents regret; most people on both sides don’t experience life‑ruining regret. That means you can’t outsource your decision to “What will minimize regret?” so much as: What can I imagine living with, given who I am, my partner situation, my health, and my values?

Whatever you choose, try to build a social life. The clearest buffer against late‑life loneliness isn’t “children” in the abstract; it’s having a few close, dependable people: partners, friends, siblings, chosen family and staying engaged with community. That’s especially critical if you’re a man, since the cultural default gives you fewer built‑in supports.

Kids can absolutely be a profound source of joy and meaning. So can a life without kids, if it’s aligned with who you are and you’re intentional about relationships and purpose.

The old line: “Women who don’t have kids will be miserable, and men will be fine” just doesn’t hold up. The truer, if less catchy, version is something like:

Some parents suffer, some non‑parents suffer. Most people adapt. The bigger blind spot isn’t hordes of secretly miserable childless women, it’s the isolated men drifting through a world built on the assumption that a partner and kids will always be there.

Note: You should be mindful of the fact that we have reasonably good embryo selection technology that can increase odds of your kids having an upgraded set of traits (intelligence, health, mood, etc.). You could use this if you are concerned about certain diseases/traits but still want kids. Also if you are scared about having kids due to fears of “climate change” you have been brainwashed by pseudoscientific propaganda. Global warming isn’t even a big problem (we have air conditioners) and if it becomes a serious problem we already know how to solve it (it’s already being attacked from all angles with nuclear, EVs, solar panels, etc.).