Poland and Hungary Fight for Sovereignty Against the EU Migration Pact

Poland and Hungary fight the EU bureaucrats to preserve national sovereignty

For a long time, the EU sold itself as a common market and a peace project.

But over the last decade, it’s morphed into something much more intrusive:

an engine for top‑down migration policy, enforced by courts and fines, that can override national parliaments on who gets to live inside their borders.

Countries like Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Czechia joined the EU for trade, funds and security – not to be told by Brussels how to reshape their populations.

Yet that’s exactly what the current asylum and migration system is doing:

Court orders and €200 million fines plus €1 million per day for non‑compliant Hungary. (Curia)

A “solidarity pool” that forces every member state to take asylum seekers, pay cash, or ship border guards, starting in 2026. (Consilium)

Past relocation schemes where Poland, Hungary, and Czechia were literally found to have “failed to fulfill their obligations” because they refused to take the quotas. (Curia)

Meanwhile, many of the countries resisting this push – especially in Central and Eastern Europe – are:

more homogeneous,

safer by their own citizens’ reports, and

often growing faster than the migration-heavy Western states lecturing them.

And when countries like the Netherlands and Denmark actually crunch the numbers on lifetime fiscal impact, they quietly start tightening, experimenting with return policies, and running into EU law the moment they try to discriminate between “Western” and “non‑Western” migration. (IZA)

Let’s unpack how this is playing out.

I. How EU got power over borders/sovereignty: the treaty trap

When Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia and others joined in 2004, they did not see today’s concrete rules – no €20,000‑per‑migrant solidarity fees, no 2026 relocation pools.

But they did sign treaties that:

Tell the EU to build a “common policy on asylum” and a “common immigration policy” (Articles 78 and 79 TFEU), and

Allow those policies to be made by qualified majority voting (QMV) – so a majority of governments and MEPs can pass laws that bind everyone, even states that voted no.

In 2015, that machinery was used to impose emergency relocation quotas from Greece and Italy on all other states.

When Poland, Hungary and Czechia refused, the EU Court later ruled they had broken EU law and could not hide behind domestic security concerns. (Curia)

The same machinery has now produced the new Migration and Asylum Pact and its yearly solidarity pool.

From a sovereignty‑first perspective, that’s the core problem:

Nobody told them in 2004, “In ten years you’ll be forced to take asylum quotas or pay for them.” What they did sign away, though, was the power: they agreed the EU could make future migration rules by majority vote, and that those rules would override national objections.

II. Hungary example: Fined €200 Million + €1 Million every day by the EU

The most brutal collision so far is Hungary vs the EU Court. (ECRE)

What happened?

In 2020, the Court ruled that Hungary’s “transit zone” system on the Serbian border – where asylum seekers were effectively detained and pushed back – violated EU asylum and return law.

Hungary closed the camps but kept a system that, in practice, still made it almost impossible to lodge asylum claims at the border.

In June 2024, the Court said enough:

Hungary had failed to comply with the 2020 judgment and was “seriously undermining” solidarity among member states. (Curia)

It imposed an “unprecedented” penalty:

€200 million lump sum, plus

€1 million per day until Hungary fixes its asylum system.

Hungary missed the payment deadline in 2024. The Commission can now simply deduct the fines from EU funds that would otherwise go to Budapest. (JURIST)

This is not abstract.

Brussels and the Court using the EU’s financial plumbing to punish a government for how it polices its own border and who it lets apply for asylum.

You can support strict asylum enforcement or oppose it – but calling this a sovereignty clash is just describing what’s happening.

III. 2015 Quotas: Poland, Hungary, Czechia vs the relocation machine

The earlier trial run was the 2015–17 relocation scheme:

Council decisions required member states to relocate fixed numbers of asylum seekers from Greece and Italy after the 2015 crisis. (ASIL)

Poland, Hungary and Czechia basically refused.

On 2 April 2020, the Court held that all three had “failed to fulfill their obligations” under EU law by not relocating applicants as required. (Curia)

No financial penalties that time – the scheme had expired – but the precedent is crystal clear:

If a majority in Council votes for relocation decisions, individual states cannot legally say “no thanks.”

That is exactly the mechanism the new pact builds on.

IV. The new migration pact: “solidarity” by force

The Pact on Migration and Asylum, adopted in 2024 and due to apply from June 2026, has 3 big planks (Consilium)

Harder external border & returns: Fast‑track border procedures, expanded use of “safe third country” concepts, and return hubs for rejected applicants. (Reuters)

Common asylum rules: Standardized screening and accelerated procedures for people from “safe countries of origin”, making it easier to reject claims and deport.

Annual “solidarity pool”: Every year, the EU sets a target for solidarity: relocations and/or money and/or other support.

For 2026, ministers just agreed:

21,000 relocations, or

€420 million in contributions, or

equivalent manpower/equipment.

Frontline states under “migratory pressure” – Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Italy – are eligible to receive relocations or cash. (Reuters)

Some countries (Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Poland, Bulgaria, Estonia) are recognized as already carrying a lot of the burden (especially due to Ukraine), so their obligations can be cut or waived in the first year.

But the principle is clear:

Every state must contribute something: take people, pay, or send resources.

You can’t say, “We’re in the EU but we want zero involvement in asylum flows entering through Italy or Spain.”

V. Can countries choose migrants or are they being forced to take whoever EU wants?

Under this solidarity system:

Relocation concerns asylum seekers already present in frontline states.

Many come from Middle Eastern, African, and South Asian countries, with some Latin American and others in the mix. (euronews)

States participating in relocation can:

Express preferences on profiles – families vs single adults, vulnerability, language, skills; and

Use security and health checks to reject individuals.

But they cannot say “only Europeans” or “absolutely no Africans or Middle Easterners,” because: EU law explicitly forbids direct ethnic or national‑origin discrimination by public authorities.

We’re seeing this clearly in Denmark (The Guardian):

Its “ghetto law” labels areas “parallel societies” if more than 50% of residents have a “non‑Western” background, triggering demolition, forced tenure changes and stricter rules.

In 2025, an Advocate General at the EU Court said this is direct discrimination based on ethnic origin and likely violates EU race‑equality law.

So when a state tries to explicitly separate “Western” and “non‑Western” residents, it runs straight into EU anti‑discrimination rules.

In practice, that leaves resistant states with three options:

Pay instead of relocating (roughly €20,000 per person not taken in the Commission’s original proposal).

Offer border personnel, infrastructure, or money as “alternative solidarity”.

Or refuse altogether and end up like Hungary – in court, with fines deducted from EU funds.

VI. Countries resisting migration vs. embracing migration (productivity & crime data)

The core “no thanks” bloc on EU‑managed migration is:

Poland

Hungary

Czechia

Slovakia

Austria (often aligned on the harsher “crisis” rules)

They have three things in common:

They joined in 2004 or later.

They are far more homogeneous than Western/Nordic states.

Their publics are deeply skeptical of large non‑European inflows.

Homogeneity & migration levels

On the foreign‑born share:

Poland – 2.5% foreign‑born

Bulgaria – 2.6%

Romania – 2.8%

These are the lowest foreign‑born shares in the entire EU. (Europa)

Now compare that to the big intake countries:

Germany: ~20–21% of the population foreign‑born (17.4 million people in 2024). (RFBerlin)

Sweden: ~20.3% foreign‑born in 2023, after a decade of very high asylum and family migration. (OECD)

The states pushing back hardest against Brussels’ relocation schemes are exactly the ones that have not already transformed their demographic profile.

Crime & safety

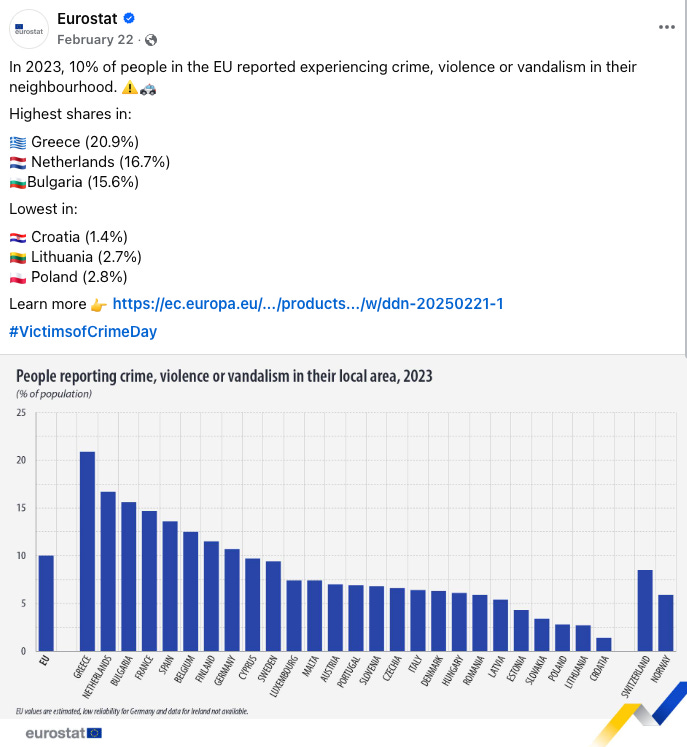

Start with how safe people say they feel in their own area.

In 2023, 10% of people in the EU said crime, violence or vandalism in their neighborhood is a problem. (Europa)

But by country:

Highest local‑crime worry (high‑intake West/South):

Greece: 20.9%

Netherlands: 16.7%

Bulgaria: 15.6%

France: 14.7%

Spain: 13.6%

Belgium: 12.5%

Lowest local‑crime worry (mostly low‑intake CEE):

Croatia: 1.4%

Lithuania: 2.7%

Poland: 2.8%

(Slovakia, Estonia, etc. also well below the EU average)

So the “we feel unsafe” map is dominated by Western/Southern states that took in large numbers of non‑EU migrants, whereas the “we feel fine” cluster is heavily Central/Eastern and low‑intake.

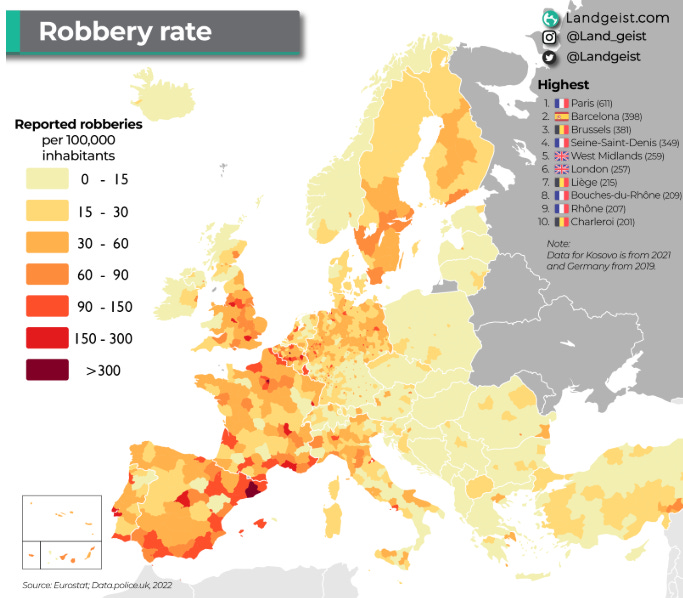

On harder crime indicators, you see the same split.

Robbery rates (2022–23):

Among the highest in the EU: Spain, Belgium, France (over 100 robberies per 100,000 inhabitants).

Lowest robbery rates: Hungary, Estonia, Slovakia, all in the low single‑digits per 100,000. (Waterford News)

Prison populations (2023):

Poland, Hungary, Czechia have the highest incarceration rates in the EU (around 180–200 prisoners per 100,000). (World Bank)

So they aren’t afraid to actually lock violent criminals up and keep them there to prevent further societal damage.

The dissenter bloc essentially runs a common sense model of:

Zero woke: Low migration + tough justice = very little visible disorder.

The compliant bloc runs a non-data-backed model of:

Woke: High migration + softer justice (often two-tier justice) = higher recorded robbery, more people saying their neighborhood feels unsafe.

And when you look inside the high‑intake states, the over‑representation of foreign‑background suspects is not a myth – it’s in their own official data.

Sweden (poster child for high intake → gang trouble):

Swedish government summary of Brå’s findings:

People born abroad are 2.5× more likely to be registered as crime suspects than Swedes with two Swedish‑born parents.

People born in Sweden to two foreign‑born parents are 3.2× more likely to be suspects.

Even after adjusting for age, sex and living conditions, the excess risk remains 1.8× and 1.7× respectively. (Regeringskansliet)

For the most serious violent offenses, the relative risks are even higher before adjustment (over 4× for some homicide/robbery categories). (Brå)

So from Warsaw, Budapest, Bratislava or Prague, the logic is very straightforward:

Common sense model: Tiny foreign‑born share, extremely low local‑crime worry, low robbery rates, very firm policing.

Woke model (Netherlands, France, Sweden, etc.): Much higher foreign‑born share, more people saying “my area feels unsafe”, much higher robbery rates in many cases, and an official acknowledgment that foreign‑background suspects are heavily over‑represented in certain crimes.

And yet it’s the second model trying to force itself on the first through EU relocation and fines.

GDP Growth

On top of that, the “rebels” are not economic basket cases – quite the opposite. (This is all very predictable if you think critically about evolution.)

Poland is the clearest example:

According to recent FT and Commission‑backed analyses, real GDP growth in Poland has averaged about 3.7% per year between 2005 and 2024, well above the EU average. (FT)

France and Germany, the traditional “core”, are now stuck in near‑stagnation – Germany in its third year of flat or negative growth, France projected at around 0.7% in 2025 – while Spain and Poland are explicitly described as the “new growth engines” of Europe. (Le Monde.fr)

Zooming out to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE):

A 2025 academic study on economic convergence finds that all CEE countries that joined after 2004 grew faster than the old EU‑14 average over the last two decades. (Taylor & Francis)

The Vienna Institute and other forecasters now expect Eastern EU economies to outgrow the euro area again, with CEE members projected around 2.6–3.0% growth vs roughly 0.6–1.6% for the eurozone in the mid‑2020s. (Erste)

Scoreboard

So the scoreboard, very crudely, looks like this:

Low‑migration CEE bloc (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, etc.)

Foreign‑born around 2–6% in many cases.

Among the lowest local‑crime worry in the EU (Poland 2.8%, Croatia 1.4%, Lithuania 2.7, Slovakia/Estonia also very low).

Very low robbery rates (Hungary, Estonia, Slovakia).

Faster growth than the EU average over the last 15–20 years; Poland in particular clearly outpacing Germany/France.

High‑migration West/North (Germany, France, Sweden, Netherlands, Belgium, Spain)

Foreign‑born shares in the mid‑teens to 20+% (Germany ~20–21%, Sweden 20.3%, etc.).

Much higher proportions of people saying local crime/violence/vandalism is a problem (up to 16–21% in some cases).

In several cases, robbery rates and gang activity are heavily concentrated in migrant‑dense urban pockets, with foreign‑background suspects clearly over‑represented.

Sluggish growth and rising political instability in core economies like Germany and France.

If you’re sitting in Warsaw or Budapest, looking at: (1) your own combination of low migration, low perceived crime, relatively strong growth vs. (2) a Western model of high migration, high perceived local disorder, and stagnation…

It’s not remotely crazy to say:

“We’re not sacrificing our safety and cohesion to copy a model that clearly isn’t working for the people who already tried it.”

Related: How the EU Extorts the U.S. via Big Tech Fines

VII. How the Rebel Bloc Actually Fights Brussels (Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, Austria)

The sovereignty bloc has been experimenting with different ways to resist and route around the EU migration regime.

1) Poland: wall + Ukraine + legal carve-outs

Poland’s strategy is basically: we decide which flows we own.

On the Belarus border, Poland treated Lukashenko’s “migrant push” as hybrid warfare: state of emergency, a 187 km steel wall, pushbacks, and a militarised frontier. Brussels and NGOs screamed; Warsaw shrugged and doubled down.

On Ukraine, Poland did the opposite: effectively open borders to millions of culturally closer refugees, instant access to work, and a huge, GDP-boosting shock that actually fits Poland’s labour market.

On the Migration Pact, Warsaw has now forced reality into the law: Poland is formally exempted from relocations in the 2026 solidarity pool, on the grounds that it already carries a massive Ukraine/Belarus burden. Net message: “We’ll do solidarity on our terms – not yours.”

So Poland’s “fight” isn’t just no-no-no. It’s: yes to the flows that make sense for us, hard no to Brussels pick-and-mix quotas from Italy or Greece.

2) Hungary: full confrontation and legal guerrilla warfare

Hungary is the pure, open confrontation model:

Built the Serbia fence early, made itself the lightning rod of EU outrage.

Created transit zones and a near-zero-access asylum system, got punched by the Court, then half-complied on paper and kept pushing in practice.

Now sits under a €200m + €1m/day fine and basically dares the Commission to claw the money back from cohesion funds while Orbán sells himself domestically as “the man stopping Brussels and illegal migration.”

Hungary is the warning shot: if you go all the way to open legal defiance, Brussels will use the full infringement + fines toolkit against you.

3) Czechia & Slovakia: strategic hitchhikers

Czechia and Slovakia are more cautious, but they’re riding the same current:

Both have resisted relocation from the start, sided with Poland and Hungary on quotas, and now lean heavily on “we already host huge numbers of Ukrainians” to argue for relief.

Czechia in particular has quietly secured solidarity exemptions, framing itself as another over-burdened frontline state (Ukraine inflow, not boats).

Slovakia’s current government is openly hostile to imposed migration and has signalled, via constitutional tinkering and rhetoric, that it does not accept EU law dictating who lives in Slovakia long-term.

They’re not taking as many headline fights at the Court as Hungary, but they’re constantly angling for carve-outs and minimum compliance.

4) Austria: half inside, half Visegrád

Austria is useful because it shows this isn’t just “crazy Easterners”:

Vienna has a very high foreign-born share already, absorbed big refugee waves, and still votes against the harshest parts of the migration pact and keeps temporary border checks with neighbours.

Politically, Austria often lines up with Hungary and the CEE bloc on “no further relocations”, even while being more integrated with Western elites.

Austria’s game is: we already paid our migration price; we’re not letting Brussels pile on indefinitely.

VIII. When countries actually track the costs: Netherlands & Denmark

It’s not just CEE governments on instinct. Some of the most data‑driven countries – Netherlands and Denmark – are quietly moving towards a more restrictive model.

Netherlands (Gold Standard Tracking)

In 2024, Jan van de Beek and co‑authors published “The Long‑Term Fiscal Impact of Immigrants in the Netherlands Differentiated by Motive, Source Region and Generation.” (IZA)

Using microdata for the entire population, they compute discounted lifetime net fiscal contributions (taxes paid minus benefits/services consumed) by:

Immigration motive

Source region

Generation

Headline findings (in plain language):

Labor migrants: On average net positive lifetime contributors (mostly other White ethnic Europeans).

Study migrants, family migrants, and asylum migrants: Massively net negative over their lifetimes and subsequent second-and-third generations.

They also show that only a minority of immigrants are net lifetime fiscal contributors; the rest are net receivers in the Dutch welfare state.

This is exactly the “lifetime, granular” picture we need to consider.

What has the Netherlands been doing politically?

Tightening family reunification and asylum, including stricter conditions and more temporary statuses.

Restricting low‑wage labour and some student inflows, focusing more on high‑skilled migration.

Closing access for new applicants to its old “remigration benefit” scheme for older non‑Western migrants as of 1 January 2025, although existing beneficiaries keep it. (The Guardian)

So the country with the most detailed, uncomfortable fiscal data doesn’t respond with “open borders”: it responds with tighter filters and more temporary protection.

Denmark: integration by force – until EU law steps in

Denmark, one of the most hardline countries inside the EU system, has:

Reduced refuge into temporary protection, with the explicit goal of sending people back when their home country is deemed safe.

Implemented the famous “ghetto package,” targeting areas where more than 50% of residents are of “non‑Western” origin, with tools like reducing social housing, demolition, and stricter penalties. (The Guardian)

And what happens? In 2025: An Advocate General at the EU Court says Denmark’s scheme is directly discriminatory on ethnic grounds and likely violates the EU Race Equality Directive.

In other words:

When a national government actually acts on the logic of “non‑Western concentration is a problem,” it collides head‑on with EU anti‑discrimination law.

So the politics are heading one way (tougher integration, less permanent settlement), while the legal super‑structure still makes it hard to target the specific dynamics driving welfare and cohesion costs.

IX. Why Brussels pretends granular data doesn’t exist

How can the EU ignore the actual data? They don’t exactly ignore it – they zoom out to a different level.

Demographers and EU institutions point to the historic low in births – only 3.665 million babies in the EU in 2023, the lowest since records began – and argue that immigration is needed to maintain the workforce. (FT)

Economic bodies like the IMF and OECD highlight that, at the aggregate, the fiscal effects of migration are often within ±1% of GDP: small enough to be “manageable” with policy tweaks.

They can point to cases like Spain, where immigration has fueled a population rebound and a big share of job growth (roughly 88% of new jobs in 2024 going to foreign‑born or immigrants), while GDP growth beats the EU average. (Le Monde.fr)

From that distance, the story is:

“We’re aging, we need workers, and the overall impact looks small and often positive.”

What disappears at that altitude is:

Composition of flows (labor migrants vs asylum vs family reunification)

Lifetime fiscal profile of different groups (they aren’t tracking this… head is buried deep in the sand)

Localized strain (housing, schools, hospitals, policing, translation, NGOs)

So the moronic argument that migrants are “boosting GDP” and contributing in “taxes” is so absurdly misleading it should evoke a sense of rage!

A GDP boost means absolutely nothing if the lifetime effect is net negative and the net negative contributions compound after multiple generations (as shown in van de Beek’s research).

And as van de Beek notes: this kind of work has not exactly been embraced in policymaking circles. (Likely because they fear perceptions of xenophobia… they are infected with the woke mind virus!)

This is where the “aging and GDP/workforce” story quietly flips from perceived solution to accelerant of the problem:

The standard Brussels narrative blindly assumes (with zero data) that each additional worker is, on balance, a contributor to the tax base that supports pensions, healthcare and other age‑related spending.

But if a given stream has a negative lifetime net fiscal contribution, then expanding that stream to “fix” aging doesn’t stabilize the system – it adds more future claimants than future net contributors.

In other words, you’re not just importing workers; you’re importing future pensioners and their dependants, plus the upfront costs of integrating them now. If their taxes over their life never catch up with the services they consume, the dependency ratio has been made worse than before you started.

Put crudely: If your pay‑as‑you‑go system already doesn’t balance, and you respond by scaling up a group whose expected lifetime balance is negative, you have deepened the hole while temporarily flattering the headline GDP and employment numbers.

At EU level, that nuance is easy to skate past. Eurostat charts and IMF tables operate on the macro, system‑level story, where everything is averaged together and small pluses and minuses are washed into a “broadly neutral” fiscal impact.

The composition question – which flows you are scaling when you invoke “we need migrants to save the pension system” – is politely left to national governments.

Those same national governments then get punished when they try to close the tap on the fiscally weakest flows: infringement procedures, moral condemnation, threats to funding.

Brussels keeps the comforting demographic narrative, the institutions keep the macro models that look fine in aggregate, and the messy multi‑generation arithmetic is pushed downwards – to the towns, schools, hospitals and police forces that actually have to make the numbers work.

X. How long does this drag on?

Hungary’s case

Hungary’s €200m + €1m/day fine will keep running until it complies with the Court’s 2020 asylum ruling to the Court’s satisfaction – or until some political deal is struck. (Curia)

Given that the Commission can offset unpaid fines against EU money Hungary is supposed to receive, this can effectively drag on for years, quietly eating into Budapest’s funds while the legal standoff continues. (JURIST)

The 2026 solidarity pool and beyond

The first solidarity pool (21,000 relocations / €420m) is for 2026, because the pact only starts mid‑year. (Consilium)

If Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, etc. choose to pay or send staff, there’s no dramatic confrontation – just ongoing resentment.

If any government flat‑out refuses both relocation and payment, the Commission will start infringement proceedings, leading in a few years to more Court rulings and, ultimately, more fines.

Realistically, you’re looking at:

Late 2020s: First real test cases and compliance fights.

2030s: Either the system becomes “normalized” (with states grudgingly paying/relocating), or dissenting countries push for treaty changes, opt‑outs, or, in the extreme, some form of withdrawal.

There’s no built‑in expiration date. This is open‑ended.

XI. The real choice: pooled demography vs. reclaimed borders

Stripped of the legalese and technocratic talk, the core question is simple.

Should a majority of EU governments, plus the Commission and Court, be able to bind your country into a migration and asylum regime that:

Reshapes who lives in your towns

Imposes large, long‑run fiscal and cohesion costs

Even if your own voters and parliament say “no”?

From a sovereignty‑first perspective, the answer is obviously: NO.

Countries like Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and Czechia are essentially trying to keep the benefits of EU membership (trade, funds, mobility) while maintaining control over demography and asylum.

Brussels is trying to hold the line that:

Asylum is a common policy

Solidarity is mandatory

Ethnicity‑based distinctions are forbidden, even when the underlying fiscal and social realities are stark.

Unless the treaties are rewritten to pull migration and asylum back to the national level, or to allow hard opt‑outs, this fight doesn’t go away.

It just escalates, via:

more fines

more budget claw‑backs

more home‑front anger that “we never voted for this”

The only honest resolutions are:

Treaty change

Formal opt‑outs for migration/asylum

Leaving parts of the EU system (Schengen, or the Union itself)

Until one of those happens, expect exactly what you’re already seeing:

CEE countries staying safer and more cohesive, with small foreign‑born populations and strong growth.

High‑migration Western and Nordic states wrestling with integration, local disorder, and long‑run fiscal strains.

And Brussels insisting the answer is more of the same, just better managed.

From a sovereignty‑first stance, that looks less like “solidarity” and more like a slow‑motion demographic trojan horse and political takeover of decisions that should never have left the nation‑state in the first place.

Read: Europe’s Trojan Horse: Suicidal Empathy Destroying Countries via Genetic Replacement

So what should the European Union (EU) do?

Common sense: Stop forcing sovereign EU countries to accept: refugees, asylum seekers, immigrants/migrants, etc.

Let countries make their own decisions about who they want living in their country… and let them enforce borders however they want.

If you fine them and/or force them to accept migrants, you are a threat to their sovereignty!

It is true that Europe has low birth rates. No there’s no stopping this train unless you run some sort of mass government breeding operation for healthy productive people.

Migrants will not save any economy unless countries are ultra-selective for intelligence and assimilation (i.e. doing IQ/culture-fit tests).

If you allow them to vote, they’ll vote for policies akin to more socialism and open borders; this has been observed over-and-over again.

A Dubai-like system would’ve been lightyears smarter for the EU.

You can either have: (1) infinite migrants + minimal/zero safety net + zero voting rights + harsh law enforcement OR (2) ultra-selective immigration + generous safety net + basic crime enforcement.

If you add more “lifetime net negatives” on top of an aging EU population, you just get more of a disaster than you already had. Selective immigration if you can attract elite immigrants would be a reasonable response.

Rolling out AI/robotics as rapidly as possible is another legitimate response. I’ve already written about what countries can do about “low birth rates.”

Thankfully Poland and Hungary still have some common sense… the rest continue ignoring the best fiscal impact microdata (from The Netherlands) and aren’t bothering to collect any granular data themselves in fear of being called xenophobic or racist.

Oh the horror: you might be called xenophobic or racist (even though you aren’t) and you fear being called names more than the potential destruction of your countries!

And FYI: Multi-gen microdata from van de Beek is actually skewed favorably for the migrants given that it doesn’t even account for non-gov charity (e.g. NGOs, food banks, shelters); private victim losses from crime; and other downstream effects (e.g. social/cultural cohesion drops, lower trust, exacerbation of low birth rates in natives, living in fear, etc.).

Absolute insanity. By the time the EU bothers collecting the granular data they will have been so thoroughly trojan-horsed that trying to change policy won’t matter anymore… the countries will have devolved into a shell of their former selves.

If you are Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, and Austria? You need to band together and resist the illogical virtue signaling whims of the EU bureaucracy. Take the fines and fight them as hard as possible in courts. The Netherlands, Denmark, et al. should join in on the fight. This is no longer evidence-based policy but a woke egalitarian EU fantasy. Sovereignty and identity are at serious risk.