No, $140k Is Not the Real U.S. Poverty Line

Michael Green embellishes how bad Americans have it... which fits the mainstream populist narrative. $140k income is now allegedly "crisis mode."

Michael Green’s “Part 1: My Life Is A Lie” claims that the “real” crisis poverty line for a family of four in the U.S. is around $140,000, based on national-average spending, and then argues high-cost zip codes would need even more.

I’m not entirely sure why this piece went viral… but it did. Maybe some coordinated promotional effort for his blog? Who knows.

Many people strongly agree with Green because they:

Have a sense of entitlement to live in a specific location and want maintain a specific lifestyle without compromising on spending/behaviors (hedonic adaptation to current SES)

Are comparing themselves to Elon Musk, TikTok celebrities, and IG models

Are being told by the mainstream media how poor they are (if you hear it enough you start to believe it)

It’s EXTREMELY EASY to rant about “income inequality” and how terrible everything is for the poor and middle class… people lap this shit up… you are telling them exactly what they want to hear.

It’s also beyond easy to scapegoat the “wealthy” and “rich” because they are a small percentage of the population… who will defend them?

eViL gReEdY billionaires like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are always to blame… cue Bernie, AOC, et al: with pitchforks out: “They aren’t paying their fair share!”

The prevailing sentiment is something like: The poor can do no wrong! The rich are evil! The middle class is left behind!

Feelings don’t care about your facts (the correct world model)… people want you to confirm their preexisting feelings and they want to ignore facts.

Green’s essay:

Is emotionally effective and goes along with the mainstream media brainwashing telling people 24/7 they are trapped and poor no matter what they earn.

Synergizes with populist Gen-Z delusion that financial success in the U.S. equals an annual income of $588k and a net worth of $9.47 million. (Gen-Z vs. Boomers)

The reality is that you shouldn’t even need a complex breakdown to know that implying $80k is “deep poverty” is borderline comedic.

Maybe relative poverty in highly-specific desired jurisdictions if you have a family of four, but certainly not what most would consider true poverty.

If you showed Green’s “$140,000 is the real poverty line” to the Founding Fathers, the Silent Generation, the Amish, or a family scraping by in rural India or sub‑Saharan Africa, they wouldn’t nod solemnly… they’d think we’d lost our damn minds.

The Founders built lives and institutions out of literal wilderness. The Silent Gen remembers rationing, war, and living on meat‑and‑potatoes austerity. Amish communities still raise large families on low cash incomes with almost no consumer frills. Hundreds of millions of the global poor are trying to survive on a few dollars a day.

From their vantage point, redefining “poverty” upward until it means “can’t sustain a high‑cost, convenience‑maxed, coastal‑metro lifestyle without stress” wouldn’t look like compassion; it would look like peak civilizational decadence — a society so materially rich it can afford to treat discomfort as deprivation and preferences as rights.

So what is going on in Green’s blog? A few things:

Redefine poverty upward until a very specific, expensive, coastal‑metro lifestyle counts as “crisis.”

Downplay how much agency and incentives matter in individual choices (where to live, family structure, job moves) and lean heavily on “the system” as the main story.

Ignore the actual scale and structure of government transfers, and the way regulation and subsidies drive prices, while implicitly treating neoliberalism as the villain.

If you start from the fact that humans are naturally in poverty, not prosperity, and look at the data on how we actually measure poverty and transfers, a very different picture emerges.

Everyone acts like we live in a pure free‑market hellscape when in reality the core sectors (housing, healthcare, education, childcare) are some of the most regulated, subsidized, and distorted parts of the entire economy.

1. The natural baseline really is poverty, not “middle class”

Strip away modern capital and tech, and the default human condition is poverty. This is not an “opinion”… this is what the last few centuries of human existence were.

In 1990, about 2.3 billion people lived in extreme poverty by World Bank standards.

As of 2025, that number is around 830 million (1.5 billion fewer people in extreme poverty in a generation). (World Bank)

That transformation came from productivity, trade, and broadly market‑based capitalism.

So when someone tells me that a 2‑adult U.S. household making, say, $80k is in “deep poverty,” my first reaction is:

OK, so you changed the definition of “poverty.”

And that’s exactly what’s going on.

2. How poverty is actually measured (and why Green’s story hides that)

A) The 1960s “food × 3” line is crude

The U.S. official poverty measure (OPM) really does come from Mollie Orshansky in the 1960s:

She took the cost of a bare‑bones “economy food plan” for a family,

Multiplied by 3, because low‑income families spent about one‑third of their budgets on food,

Then indexed it to inflation forever.

That is obviously dated. It was meant as a “are you clearly in trouble?” line, not “this is what a 2025 middle‑class lifestyle should look like.”

What Green doesn’t emphasize is: the OPM is not the only game in town anymore.

B) The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) already fixes a lot of this

Since 2011, the Census Bureau has published the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) alongside the old one. SPM:

Adds non‑cash benefits (SNAP, school meals, housing assistance, tax credits).

Subtracts taxes, work expenses, and out‑of‑pocket medical costs.

Adjusts thresholds for local housing costs.

In other words: serious people already use more sophisticated measures that reflect modern spending patterns and the safety net he largely minimizes or abstracts away from.

SPM isn’t perfect, but the whole “we’re using a 1963 food rule and lying to ourselves” framing is at least 15 years out of date.

C) Once you include taxes, transfers, and better price indices, U.S. poverty falls a lot

A ton of recent work goes beyond both OPM and SPM, using:

After‑tax income

Plus non‑cash transfers

Or consumption (which tends to be better reported for low‑income households and reflects actual living standards). (NBER)

Some highlights:

Han, Meyer, and Sullivan (2023) find that when you correct for inflation bias and use consumption, U.S. consumption poverty fell from ~33.8% in 1980 to 6.0% in 2022, while the official poverty rate barely moved. (Notre Dame)

Burkhauser et al. (2019) construct a “full‑income” measure (cash income + taxes + major in‑kind transfers) and find poverty (by Lyndon Johnson’s original standard) falls from 19.5% in 1963 to 2.3% in 2017. (SSRN)

You can argue with thresholds and methods, but the takeaway is clear:

If you measure resources realistically (including modern transfers and better price indexes) U.S. poverty plunges over time instead of hovering forever.

Green’s move is the opposite: instead of updating the measure in a coherent way, he blows up the threshold to $140k and declares almost everyone poor.

3. The 16× multiplier trick: nice rhetoric, bad economics

Green’s headline math is:

In the 1960s, low‑income households spent ~33% of income on food → poverty line = 3× food budget.

Today, “food at home” is ~5–7% of spending for most households.

Take 6% as a midpoint →

1 ÷ 0.06 ≈ 16→ poverty line = 16× food budget.Run that through today’s food costs and, voilà, a $130–150k “crisis line” for a family of four.

That’s where his “16× the food budget” comes from.

Now, here’s what changed under the hood.

Engel’s Law 101: As income rises, the share of income spent on food falls. Poor households still spend a lot of their budget on food; rich ones spend proportionally much less. (IPUMS)

Orshansky’s move in the 1960s:

Looked specifically at low‑income family budgets, where food was about one‑third of spending.

Priced a USDA “Economy Food Plan” (bare‑bones but nutritionally adequate diet).

Developed a simple rule of thumb:

“Minimum food plan × 3 ≈ total income needed not to be in obvious trouble.”

Mathematically: If poor families spend ~33% on food, total income ≈ food cost ÷ 0.33 ≈ 3×. That’s all “3×” ever was: 1 ÷ (food share for poor households back then). A 1960s hack in a world where food dominated poor families’ budgets.

Michael Green:

Takes today’s national average “food-at-home” share of ~5-7% (mixing poor, middle-class, and rich budgets)

Inverts that share to get ~16x

Suggests this is how Orshansky would do it now

Orshansky updated for 2025:

If you wanted to actually follow Orshansky’s logic for 2025, you’d focus on today’s low-income budget shares NOT a national average.

BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey data suggest the lowest‑income quintile still spends on the order of ~15–16% of their total budget on food, versus ~11% for the highest‑income quintile.

Take that low‑income share:

16% →

1 ÷ 0.16 ≈ 6.25→ call it a ~6× multiplier (not 16×)

So an “Orshansky‑style” update would give you a multiplier in the rough 5–7× range, not a dramatic 16×.

Green’s $140k “floor” depends on quietly swapping in a national‑average food share pulled down by richer households and then doing the same inverse trick.

And stepping back, the whole “food share × multiplier” approach is REALLY DUMB today anyway.

In 1963 it was a useful hack because:

Food was easy to price, and

Food dominated poor families’ budgets.

Today we can do much better:

Directly price a bare‑bones but nutritionally adequate diet for a family of four.

Use modern full‑income or consumption‑based poverty measures that already account for taxes, transfers, and actual spending patterns.

If you play Green’s bizarre game in a very rich country where food is, say, 4% of average spending, you’d conclude “true poverty” is 25× the food budget and suddenly most of the population is “in poverty.”

At that point you’re not measuring deprivation; you’re stretching a 1960s food rule until it spits out whatever number fits the vibe.

Green implies he’s updating Orshansky “honestly,” but Orshansky anchored her multiplier in low‑income budgets, not a national average dragged down by wealthier households. On her own terms, it’s hard to see her leaping from 3× to 16× in 2025 then calling $140k the “real poverty line.”

4. His $136k “basic needs” budget is really a high‑burn lifestyle template

Green builds a detailed “Basic Needs / Participation” budget for a 2‑adult, 2‑kid household and arrives at roughly $136,500 gross as the “floor” to function without being in crisis.

He explicitly says he’s using “conservative, national‑average data.”

The subsequent Caldwell, NJ comparison is presented as a check showing that “in the zip codes where the jobs are,” the threshold would be even higher (his claim is >$160k).

Look at what’s implicitly baked into that:

Location: A place like Caldwell, NJ — high‑cost Northeast suburb.

Work model: 2 full‑time careers.

Kids: 2 small children in full‑time commercial daycare.

Transport: 2 cars, commuting into expensive metros (plus insurance).

Housing: Own unit in a desirable school district, no roommates, no multi‑generational housing.

Care/support: Minimal extended family or community help; every service is bought retail.

None of these are crazy choices. But they are choices.

Millions of non‑poor families do at least some of the following:

Live in lower‑cost metros or states.

Have one full‑time and one part‑time/stay‑at‑home parent.

Use grandparents, relatives, or co‑ops for childcare.

House‑share or live smaller/denser.

Drive one car instead of two.

Delay children, or have fewer children.

Those trade‑offs might be annoying but they’re not poverty.

Green hard‑codes the most expensive configuration, in a high‑cost zip, and then brands anyone who can’t afford it as “working poor.”

This is mostly measuring entitlement for a very specific lifestyle.

Even on his own terms, he uses national‑average data when it suits him, then pivots to a high‑cost New Jersey suburb when he wants to show the model is “optimistic.”

If you’re going to argue that the “real” poverty line is $140k or $160k, you can’t just blend national averages with a cherry‑picked expensive zip code and call that a universal crisis threshold.

At minimum you’d want metro‑specific thresholds, not a single line that pretends Mississippi and suburban North Jersey are equivalent.

5. Location is not a “human right”; it’s part of the consumption bundle

In practice, his argument treats living where the “good jobs” are (often some of the most regulated, high‑cost metros in the country) as the baseline assumption.

But:

Regional price parity data from the BEA shows huge differences in price levels across states and metros; housing is the big driver. California’s rent is ~3× Mississippi’s; with DC’s even higher.

People are already voting with their feet: high‑cost, high‑tax states (New York, California, New Jersey) have had persistent net domestic out‑migration to lower‑cost states in the South and Mountain West. (Fraser Institute)

Moving is a choice (the single biggest lever most households control): If your math doesn’t work in a premium zip code, you can raise income or lower costs. Location is the largest cost driver. Millions vote with their feet every year toward cheaper metros and states with lower taxes, easier commutes, and saner housing markets.

Agency: Choosing to stay in a high‑cost coastal metro for schools, restaurants, status, or network is a legitimate preference, but it’s a preference. It doesn’t convert a self‑selected, expensive lifestyle into “poverty.”

If your definition of “poverty” requires the expensive option, you’ve just re‑labeled personal preferences as rights.

A house in rural Ohio is a different product from a house in suburban North Jersey. Location is part of the consumption bundle… and insisting on an expensive bundle isn’t evidence of deprivation.

Note: I’ve noticed that Democrats/Liberals continue pushing for everything as a “basic human right.” Free healthcare, free food, free cell phones, free, free free… if we’re around long enough AOC, Warren, Bernie, et al. will be claiming trips to Mars on a SpaceX rocket are a human right. These people either: (A) don’t understand incentives; (B) are grifting for power/clout/votes; (C) enjoy socialist parasitism (extracting from productive to fund inefficient “peer-reviewed high ROI” gov programs… a.k.a. money pits)… Demanding free stuff means someone else is coerced into performing a service for nothing.

6. Composition matters: immigrants, off‑the‑books work, and under‑reported income

When Green talks about “the poor,” he implicitly imagines native‑born families like his Caldwell archetype.

But the low‑income pool in U.S. data includes:

Native‑born low‑skill workers

Legal immigrants

Newly legalized immigrants

Undocumented immigrants

A sizable chunk of that population:

Works partly off the books in construction, agriculture, restaurants, childcare, etc.

Has cash income and informal support that doesn’t show up in official earnings.

Pays taxes (especially sales, payroll, and property taxes), but often has limited access to benefits. (ITEP)

At the same time, a large literature finds that low‑income households frequently under‑report income and transfers, meaning official income poverty exaggerates how poor they are relative to their consumption. (NBER)

So you end up with:

Households that look extremely poor on income but consume significantly more

Households with off‑the‑books work plus in‑kind benefits

Households cushioned by charities, food banks, and informal help

None of that fits neatly into his “middle class vs poor” dichotomy.

The measurement and the composition make it dishonest to simply call all low‑reported‑income households “in deep poverty” without acknowledging off‑the‑books labor and non‑government support.

A meaningful slice of this “poor” population consists of unauthorized or recently legalized immigrants working off the books at very low wages. Some of them can still access benefits (directly or indirectly, e.g., via a citizen household member or identity fraud), and because they’re willing to work for less, they undercut the wages that low‑skill native workers could demand.

We don’t have clean public data on exactly how big this group is, but pretending it doesn’t exist and treating “the poor” as one homogeneous block while showing a GDP chart is misleading.

7. The safety net is huge (and badly designed)

A) Scale: transfers and welfare are not some rounding error

Green focuses almost entirely on private costs and benefit cliffs; he spends almost no time on the overall scale of the welfare state.

In reality:

Total means‑tested welfare spending (federal + state + local) is on the order of $1.8 trillion per year across ~130–140 programs. (Cato Institute)

Government transfers (including Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment, tax credits, etc.) were about $3.8 trillion in 2022, roughly 17.6% of all personal income; the average American received about $11,500 in transfer income that year. (EIG)

CBO and Tax Foundation analyses show that after taxes and transfers, the lowest‑income quintile’s average resources rise dramatically relative to market income; one estimate finds they receive net transfers equal to about 127% of their market income. (CBO)

Recent estimates by Kearney & Sullivan suggest that taxes and in‑kind transfers cut a pre‑tax poverty rate of ~17.4% down to ~6.1% in 2023. (Economic Strategy)

So, no: the system is not “pretending the poor don’t exist.” It spends staggering sums on them.

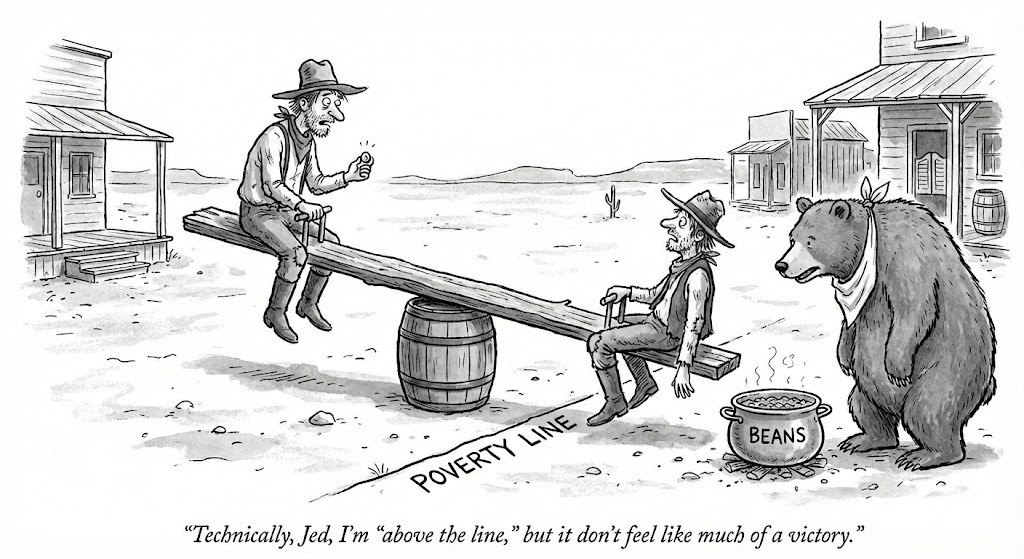

B) Design: benefit cliffs are real incentive killers

Where I agree with Green: the structure of benefits is a mess.

As you increase earnings:

You can lose Medicaid, SNAP, housing assistance, childcare subsidies, ACA premium support, etc.

While your payroll and income taxes go up.

The combined effect is a very high effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) in certain bands — sometimes close to or above 100%, where earning more leaves you no better off or even worse off.

Federal Reserve and Urban Institute work has documented very sharp cliffs around childcare, housing, and health subsidies in particular. (IRP)

This is exactly the “Valley of Death” he gestures at — but his conclusion is backwards. The cliffs don’t prove that $100k = poverty; they prove our means‑testing architecture is insane.

My view:

Keep some kind of floor: The floor should keep people from starving, not guarantee a specific lifestyle in a specific zip code. You get to choose where you live and how many kids you have, but you don’t get to send the bill for those choices to everyone else.

Radically simplify and smooth it: Negative income tax / EITC‑style credits.

So you don’t have 5–6 programs phasing out at once and nuking the payoff for working and advancing

His instinct is to layer even more clever programs on top of the ones that already produced this tangle.

8. Cost disease is real — but driven by regulation + subsidy, not laissez‑faire

We agree on which sectors are crushing people:

Housing

Healthcare

Childcare

Higher Ed

We do not agree on why.

A) Housing: strangled by zoning, not by “capitalism”

There’s now a huge empirical literature showing that restrictive zoning and land‑use rules in high‑demand metros:

Constrain supply

Drive up prices

Deepen segregation

This is textbook “supply choked by policy.”

Compare heavily zoned coastal U.S. cities with places like Tokyo, which allows much more building and has far more moderate housing costs despite being extremely rich and dense. The difference is not “more capitalism” vs “less” — it’s whether you let people build.

Green implicitly treats this as a failure of “neoliberalism” instead of saying:

We cartelized urban land use via local government, then acted shocked when prices exploded.

Note: I’ve already written what needs to be done about the U.S. Housing Crisis in 2025: deregulation (YIMBY), harsh law enforcement, no gov subsidized housing or forced DEI, stop illegal immigration.

B) Healthcare: a regulated, subsidized, third‑party maze that also funds global R&D

U.S. healthcare is a triple hybrid:

Heavy federal programs (Medicare, Medicaid, ACA subsidies),

Employer‑based, tax‑advantaged insurance,

Extremely regulated provider and insurer markets (licensing, certificate‑of‑need, network rules).

Plus:

The U.S. funds 70–75% of global pharma profits with less than 5% of world population. (White House)

When people point at high U.S. health spending, they often ignore:

We’re older age and sicker (more obesity, chronic disease) and drive more

We use far more healthcare with far better technology

We’re effectively subsidizing drug and biotech innovation for the rest of the world

There’s tons of waste (administrative overhead, opaque pricing, hospital consolidation) but this is not “pure free market gone wild.”

It’s a bizarro world of admin bloat + price‑insensitive demand + global R&D cross‑subsidies.

Green uses those high costs as another brick his argument that families under his $140k threshold are effectively poor, without separating:

Value (longer, healthier lives with 2025 tech)

Innovation subsidies

True deadweight loss from policies and cartel behavior

C) Childcare and college: licensing, credential inflation, easy money

Childcare costs rose because:

Households moved from one parent at home to both parents in the labor force, so we monetized a previously informal service.

Licensing and ratio rules raise operating costs, and zoning often blocks small/local centers. (ASPE)

Higher ed costs exploded because:

Federal loans and grants pumped demand

Colleges responded by raising tuition and building administrative empires and amenities (Cato Institute)

Again, none of this is clean free‑market capitalism. It’s subsidized, over‑regulated quasi‑cartels with little downside for providers.

So yes: cost of some “tickets” (housing, childcare, college, healthcare) is brutally high. But if you blame “markets” in the abstract instead of the policy‑created environment those markets operate in, you’re going to demand the wrong fixes.

9. Education, ability, and why “free college” is the wrong tool

In a different essay “Pandora’s Ledger: Mispriced Hope”, Green lays out a concrete “solution set,” including making public higher education tuition‑free for the bottom 50% of earners, plus more generous stipends and healthcare guarantees.

That sounds compassionate. It still ignores a couple of hard constraints:

Ability and preparation differ. Not everyone thrives in 4‑year academic tracks. A lot of marginal students are under‑prepared, and many will pick majors that don’t actually raise their earning power.

ROI varies wildly by field and program. Free education can teach people things, but it doesn’t automatically produce a positive lifetime payoff. Some degrees are effectively a consumption good, not an investment.

The FREOPP ROI study crunches data on ~53,000 programs:

31% of students are in programs with negative ROI — they lose money over a lifetime relative vs. not going.

About 23% of bachelor’s programs and 43% of associate programs have negative ROI.

STEM and some professional degrees (engineering, CS, nursing, some econ/business) have high ROI. A lot of arts, some social sciences, and generic “liberal studies” tracks do not.

Most people also don’t have the intellectual chops to cut it in many of these “STEM” majors… pretending everyone should waltz through engineering degrees is absurd… will just waste time and tax dollars.

If you make all of that “free”… you:

Insulate students and schools from cost signals

Encourage marginal students into programs they won’t finish or won’t benefit from

Give colleges even less reason to cut costs or kill low‑ROI majors

And remember: “tuition‑free public college for the bottom 50% + stipends + richer healthcare guarantees” is not some tiny technocratic tweak — it’s a big new entitlement. You’d be shifting a huge chunk of tuition and living costs onto taxpayers and likely pulling more marginal students into the system. That’s a recipe for much higher government spending funneled into exactly the same universities that already drove costs up faster than inflation.

In theory, you could design a very narrow, merit‑screened, ROI‑screened system that only funds capable students into high‑return programs or trades. In practice, once “free college for the bottom 50%” becomes a political slogan, it won’t stay that narrow. You end up socializing the downside of a lot of bad educational bets while letting the institutions keep the upside.

This would be an incentives shift that respects ability constraints and feedback loops instead of pretending everyone should be subsidized into a BA, regardless of fit.

10. Mid‑century America was a one‑off, not a natural baseline

A lot of Green’s vibe is “the middle class once thrived, now they’re drowning.”

There’s some truth here:

Chetty et al. show absolute mobility (earning more than your parents, inflation‑adjusted) fell from ~90% for the 1940 birth cohort to ~50% for those born in the 1980s. (Science)

But the 1950s–60s were way different:

The U.S. had almost no industrialized competitors (Europe and Japan were rebuilding).

Demographics were ideal (baby boom, high labor‑force growth).

We had huge low‑hanging productivity gains.

You don’t recreate that by redefining poverty until 50% of the country qualifies and then piling more complex programs on top of the existing state.

Zoom out globally and look at economic freedom vs living standards:

Countries in the freest quartile of the Fraser Economic Freedom index have incomes ~6–7× higher, and the poorest 10% earn ~8× as much as their counterparts in the least free quartile; life expectancy is ~17 years longer.

The pattern is clear: relatively freer markets (with the rule of law) produce much higher absolute living standards for the bottom, even if inequality is higher.

The problem isn’t that we “neoliberalized” too hard, rather it’s that we liberalized global capital and trade while leaving domestic housing + healthcare + education as overregulated, subsidy‑bloated messes.

If anything, we didn’t neoliberalize hard enough where it would actually lower prices for normal people.

So yes, mobility slowing is problematic. But you don’t fix that by pretending we live in laissez‑faire and overlaying even more state control. You fix it by:

Unclogging the sectors where policy choked supply and choice

Designing transfers that don’t punish work and risk‑taking

And then letting people’s agency actually matter again

11. What I do agree with Green about

Green is not hallucinating the stress. Where he’s on to something:

The cost of certain “tickets” (housing in productive metros, childcare, good degrees, healthcare) has gotten high.

Benefit cliffs and high EMTRs often make it feel pointless to move from low‑income to lower‑middle ranges.

One bad break (e.g. health shock, job loss, eviction) can trigger a “phase change” where access to credit, good neighborhoods, and opportunities collapses.

Where we diverge is what we call this, and what we do about it.

He sets ~$140k as a crisis “floor” (his updated Orshansky “too little” threshold).

He labels an $80k family “in deep poverty” and even ~$100k “the new poor,” and then points toward a larger, smarter welfare‑state scaffolding to manage it.

My thoughts:

We don’t live in “wild west capitalism.” We live in a bloated, over‑regulated, subsidy‑soaked system where housing, healthcare, education, and childcare are basically government‑protected cartels, plus some half‑baked “neoliberal” finance on top. This is nowhere near a free market.

Some fixes that would likely improve things…

Flatten and shrink the tax monster. Move toward a flat (or near‑flat) tax with far lower rates, kill most carve‑outs and credits, and force government to live on a diet instead of inventing endless new programs to justify higher revenue.

Cut government spending and bureaucracy hard. Federal, state, and local government have turned into a jobs program plus compliance theater. Start closing agencies, consolidating programs, and zero‑basing budgets instead of assuming “more is always better.” (Read: The ASAP Protocol)

Deregulate the core cost drivers (housing, healthcare, education, childcare). Nuke insane zoning and land‑use rules, roll back licensing and certificate‑of‑need nonsense, and stop pretending cartelized, subsidy‑soaked sectors are “markets.”

Build more housing without DEI social engineering. Allow a ton of building (YIMBY) but stop tying upzoning to forced “mixed‑income” / DEI experiments that make existing residents slam the brakes. Let SES sorting happen organically via prices instead of top‑down “inclusion” mandates that backfire.

Stop writing blank checks to broken models. No “free college” and no unlimited federal loans. Eliminate all federal student loans and guarantees and push financing into the private market. Lenders will tie credit to ability, major, and school quality. Colleges that can’t justify their costs will be forced to cut bloat or shrink and die.

Replace the welfare maze with a simple floor. One or two clean, cash‑like supports (negative income tax / EITC‑style) with smooth phase‑outs instead of 10 overlapping programs with cliffs that punish work between $30k and $100k.

Fix immigration toward skills and enforceability. Prioritize high‑skill immigrants, actually enforce border and work laws, and stop importing net‑negative fiscal cases while pretending it’s all upside and anyone who objects is a bigot.

12. A different way to respond to the same facts

If I had to sum up my response to Green’s essay:

Stop playing definition games. Poverty should mean something like “can’t reliably meet basic needs,” not “can’t replicate a high‑cost, dual‑career, day‑care‑heavy suburban script without discomfort.”

Use better poverty metrics. SPM, full‑income, and consumption‑based measures all show large long‑run declines in U.S. poverty, once you include transfers and correct price indexes.

Attack the cost structure directly.

Deregulate land use to let housing supply respond in high‑demand areas.

Reduce barriers and cartel protections in healthcare and childcare.

Stop subsidizing low‑ROI education paths; funnel support toward programs that actually move the needle for students who can benefit.

Design transfers that don’t punish drive. Replace jagged benefit cliffs with smoother, predictable phase‑outs (negative income tax / EITC‑like credits).

Respect agency and ability. Not everyone can or should pursue the same life script. Policy needs to stop assuming equal ability and equal preferences, and instead create a system where different choices and skills can still lead to acceptable, stable lives. You aren’t entitled to go to college or live in a cushy area within a high cost metro.

Focus on absolute living standards, not envy. Measured with any halfway reasonable metric, global and U.S. poverty have fallen dramatically over time.

This doesn’t mean we ignore people who are still struggling; it means we don’t pretend that the only acceptable outcome is everyone living an upper‑middle‑class coastal lifestyle subsidized by the state.

Closing

I am NOT convinced that the real poverty line is $140,000.

The fact that people seriously think this and blindly agree with Michael Green just tells me how far detached your average person is from absolute poverty.

We can acknowledge:

Middle‑class squeeze in high‑cost metros

Brutal design of benefit cliffs

Distorted pricing of housing, healthcare, and education (from gov involvement)

… without concluding that half the country is “poor now” and only a larger, more complex government can fix it.

The things to do are straightforward: (1) fix regulations and subsidies that distorted markets; (2) simplify transfers so work/risk still pay off (fix incentives); and (3) stop moving the poverty goalposts to fit modernity.