Game Theory of Silence: Why Smart People Self-Censor When Reality is Taboo

Why many smart people don't bother questioning the dominant narrative.

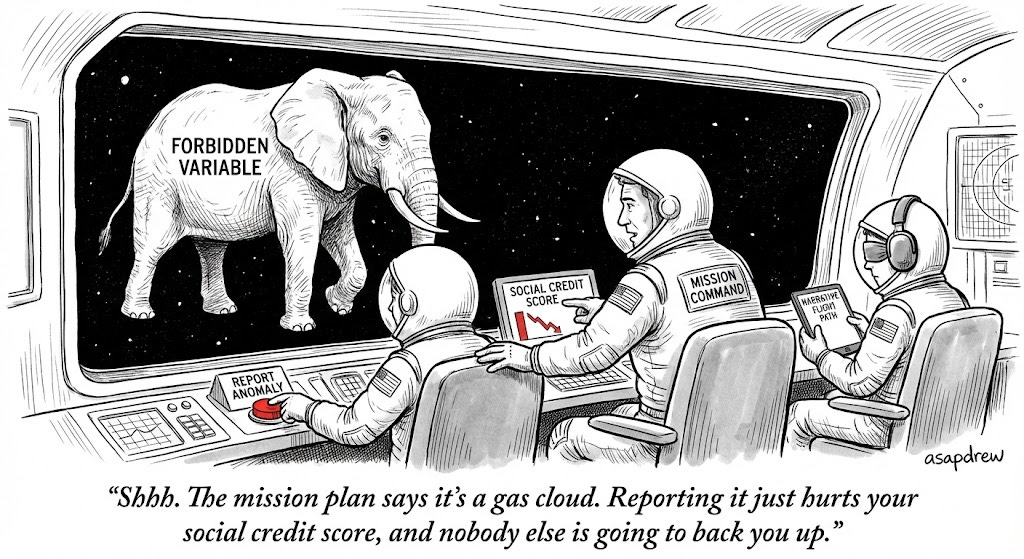

In Part 1: “The Planet That Banned 90% of Reality” — I described the mechanical failure mode: you forbid an explanatory variable, then you build education, hiring, justice, and governance as if that variable doesn’t exist.

The result isn’t just “bad discourse.” It’s distorted decisions, misallocated talent, wasted money, and a civilization that can’t model itself accurately.

But that leaves the real question:

If the costs are that big… why aren’t more smart people saying so out loud?

Why do the engineers, clinicians, researchers, and operators — people whose entire jobs revolve around reality constraints — keep their heads down?

Answer: it’s not (mostly) cowardice.

The answer is incentives: a coordination trap where silence is rational and truth is expensive.

1) Truth is a public good. Speaking is a private cost.

Start with the simplest model.

You live in a world with a taboo topic — not necessarily “race” or “sex” or “genes” or anything specific. Just a forbidden hypothesis that a lot of people privately consider plausible, and that the system publicly treats as unspeakable.

If you speak:

You pay the cost personally (HR, social shaming, career risk, reputation damage, platform enforcement).

The benefit (if any) is collective (society maybe updates, maybe reforms, maybe years later).

That’s the core asymmetry: concentrated costs, diffuse benefits.

Which means the individual utility-maximizing move is usually:

“Shut up. Let someone else take the hit.”

Even if you privately think the system is wrong, the math says: silence dominates.

That’s not a moral claim. It’s a payoff matrix.

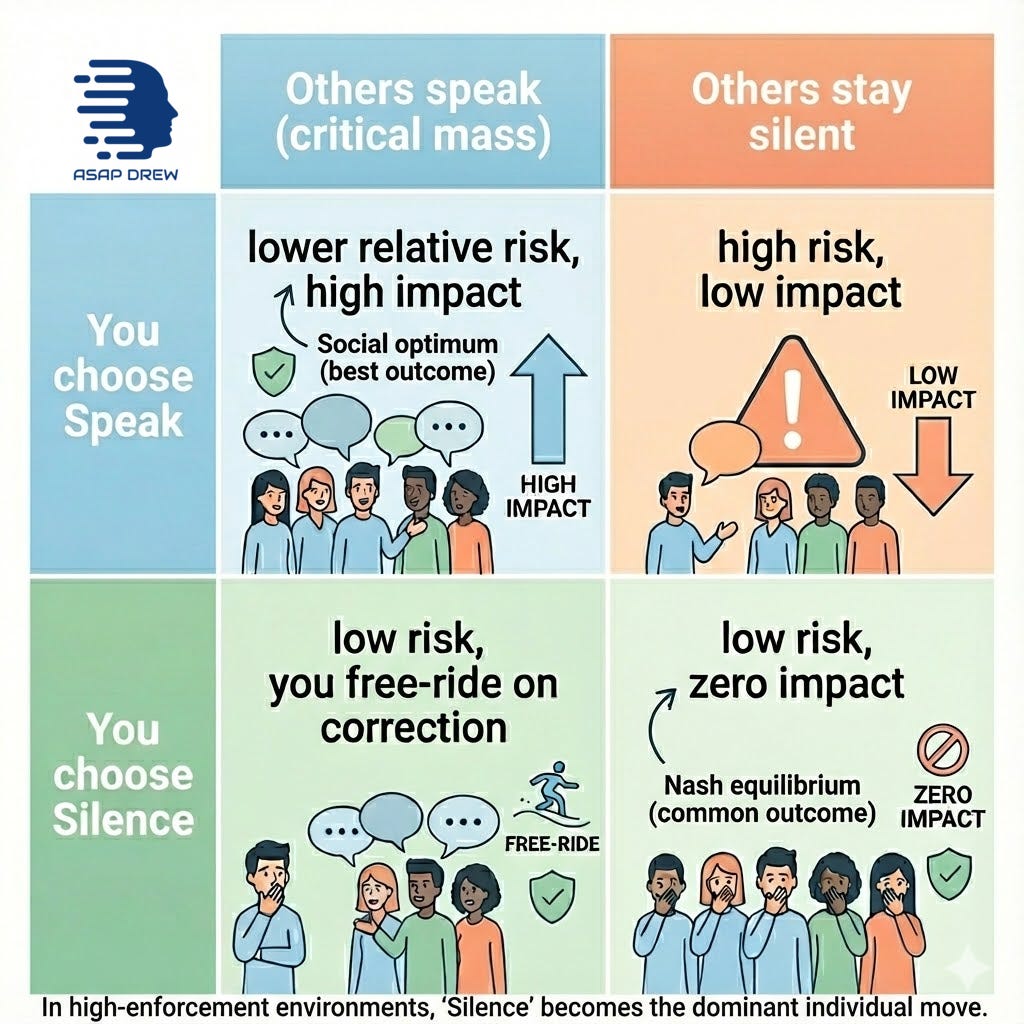

2) The Prisoner’s Dilemma version (the simplest payoff table)

Picture a professional class of 10,000 people who each privately suspect the “official model” is missing a major variable.

Each person chooses:

Speak (public dissent), or

Silence (private belief, public compliance)

And each person’s payoff depends on what others do.

A) If you speak alone:

You get tagged as a crank / extremist / bad person / liability.

You lose status. You lose opportunities. You may lose your job. You change almost nothing.

B) If everyone speaks together:

Now it’s no longer “one deviant.” It’s a new consensus.

Institutions adapt. The taboo weakens. The model updates.

C) If everyone stays silent:

The system rolls forward unchanged — and the “consensus” looks unanimous.

So you get the classic coordination trap:

Collectively optimal: many people speak.

Individually rational: almost everyone stays silent.

That’s why the “why doesn’t anyone say it?” question is naive.

The correct question is:

“What are the payoffs for being early?”

And in most environments, the payoff for being early is negative.

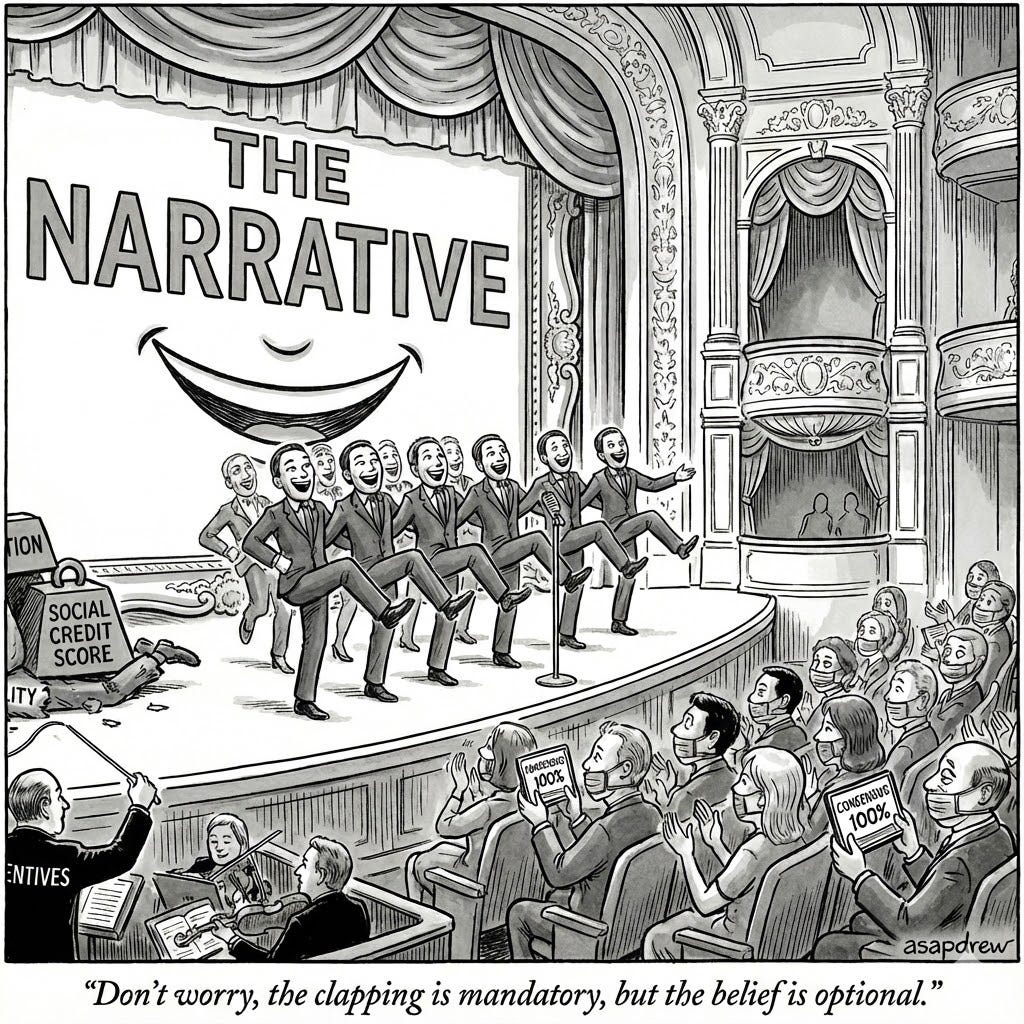

3) Preference falsification: “living a lie” as equilibrium behavior

Once silence becomes the dominant strategy, you don’t just get quiet.

You get something more corrosive: people actively perform belief they don’t hold.

Timur Kuran coined the term “preference falsification” for exactly this dynamic: when individuals publicly misrepresent their private beliefs because the social cost of honesty is too high.

The important point is not the vocabulary.

The important point is what it produces:

A public “consensus” that is not a consensus.

People watching everyone else comply and concluding: “Wow, everyone must really believe this.”

Institutions mistaking compliance for conviction.

Preference falsification is also why systems can look rock-solid — until they collapse suddenly.

Kuran’s whole thesis is that “public lies” can hide the true distribution of private beliefs until a tipping point triggers a cascade.

So if you’re asking:

“Why does it feel like everyone agrees?”

Sometimes the answer is:

“Because dissent is expensive, so disagreement goes underground.”

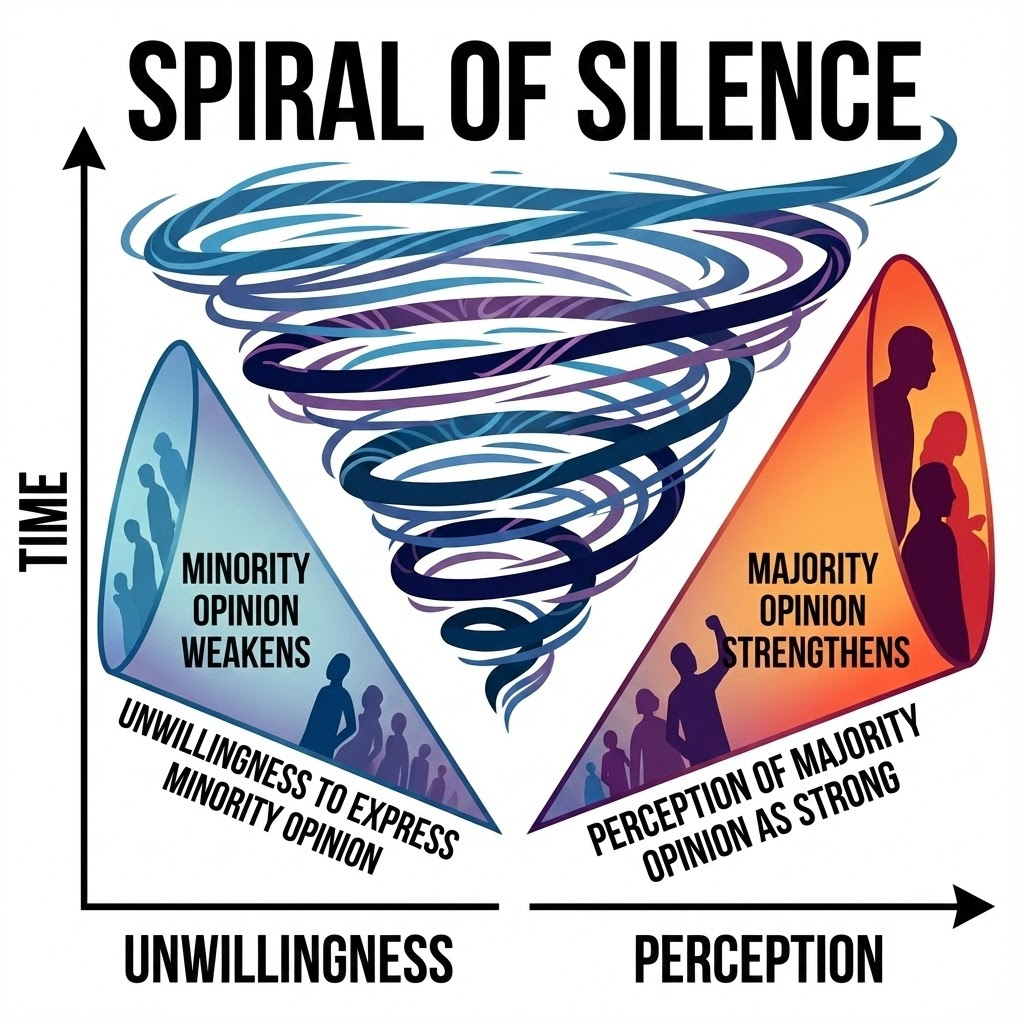

4) Spiral of Silence: fear of isolation is a force multiplier

There’s a second mechanism that makes this more stable: social fear.

Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann’s “spiral of silence” theory is basically: people are less likely to voice an opinion if they think it’s unpopular, because they fear isolation — and that silence makes the opinion seem even more unpopular, producing a spiral.

Whether you love the theory or not, the behavioral prediction is obvious and empirically testable:

People scan the room.

They estimate what’s “safe.”

They self-edit to avoid social punishment.

Which means the visible discourse is not “what people think.” It’s “what people think they’re allowed to say.”

And once AI systems, HR departments, journals, and media all amplify the same boundaries, “what’s allowed to say” becomes a far tighter box.

5) “The receipts”: self-censorship isn’t hypothetical anymore

This isn’t just clever theory.

We have direct survey evidence that large numbers of people self-censor because the social climate feels punishing.

General public: Cato reports that 62% of Americans say the political climate prevents them from saying things they believe because others might find them offensive. (Cato Institute)

Academia: A national AAC&U/AAUP/NORC-linked survey write-up reports that 52% of faculty altered their language to avoid backlash, and over half worry their scholarly activities could lead to online harassment. (Insight into Academia)

Faculty over time: FIRE’s faculty survey reports major self-censorship indicators in universities and explicitly contextualizes this trend historically. (FIRE)

You don’t need aliens to see the mechanism.

If people already self-censor at scale in a nominally free society, then a world where AI is embedded everywhere and treats certain questions as “dangerous by default” is basically industrializing the spiral.

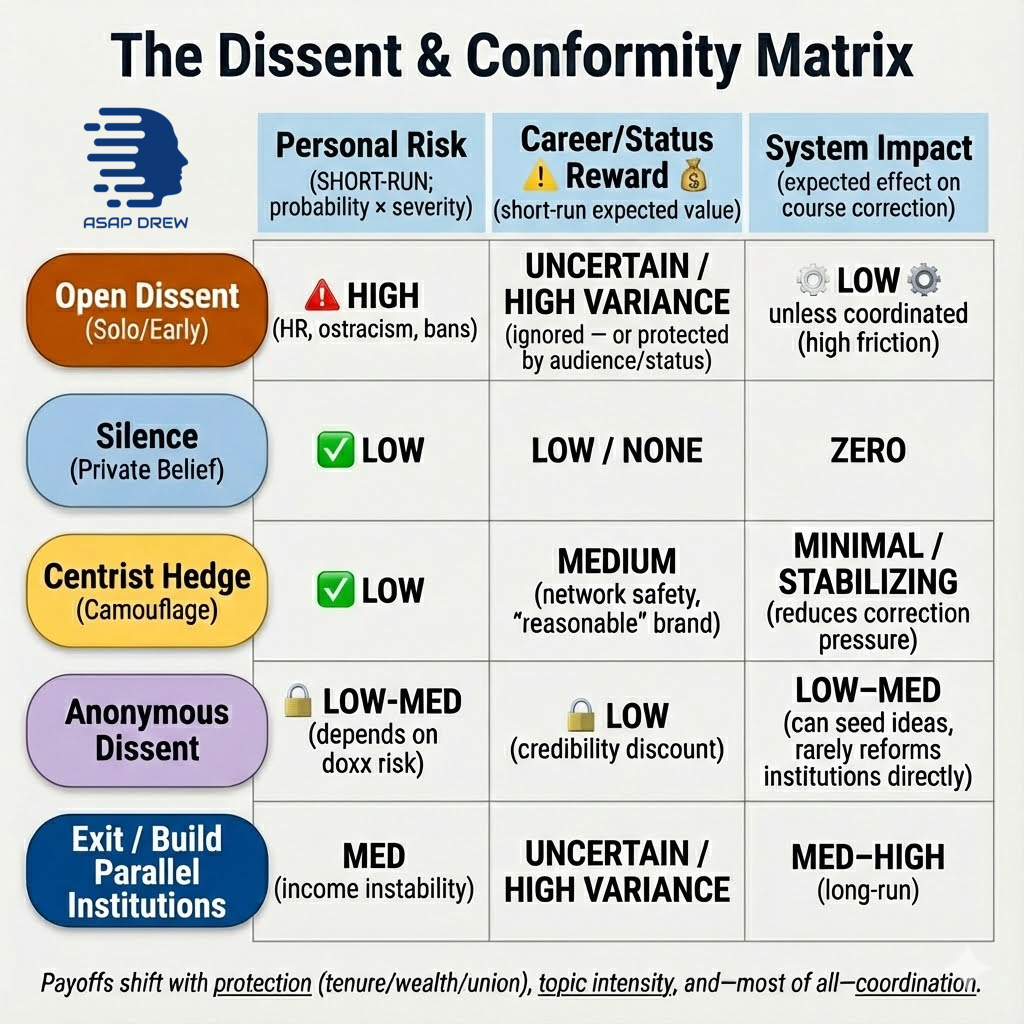

6) The missing strategy everyone forgets: not silence — amplify the lie for status, clout, money

Most discussions frame it as:

Speak, or

Stay silent

But in real systems, there’s a third strategy:

Join the lie and profit from it.

In any regime where dissent is punished, the orthodoxy becomes a career ladder.

The incentive structure looks like this:

Open dissent: High risk / low short-term reward

Silence: Low risk / low reward

Enforcement: Low risk / high reward (status, grants, promotions, platform approval, moral prestige)

So the system doesn’t just generate silence. It generates cheerleaders.

And these aren’t always dumb people.

Often, the loudest enforcers are:

Ambitious

Socially skilled

Rhetorically talented

Institutionally connected

They don’t merely comply — they innovate new justifications for why the narrative must be protected, why dissent is dangerous, why critics are immoral.

Sociologist Rob Henderson calls this dynamic Luxury Beliefs.

Just as the rich flaunt wealth with goods the poor can’t afford, the intellectual elite flaunt moral beliefs that impose costs they don’t have to pay. They champion ‘dismantling testing’ or ‘abolishing policing’ to gain status, while their wealth insulates them from the consequences. The chaos falls on the poor, but the prestige goes to the Enforcer.

This matters because it upgrades the regime from “quiet compliance” to active narrative production.

Silence makes the system stable. Enforcement makes it expand.

7) The centrist hedge: the “both sides” survival strategy

There’s another stable strategy that shows up in real human networks: The Centrist Hedge.

These are the people who privately see cracks, but don’t want to:

Lose friends on one side

Destroy work relationships on the other

Become radioactive to everyone

So they speak in a very specific dialect:

“I’m just asking questions.”

“There are good points on both sides.”

“It’s complicated.”

“I don’t know enough to have a strong opinion.”

Sometimes that’s honest humility.

But often it’s an adaptive camouflage pattern — a way to remain socially acceptable to multiple audiences without committing to claims that trigger punishment.

This is not really stupidity. It’s risk management.

And it’s another reason public discourse can drift away from private belief.

Because the hedge doesn’t correct the model. It just avoids becoming a target.

8) Anonymity trap: speak anonymously → dismissed; speak with your name → punished

So you might say:

“Fine. Speak anonymously.”

That helps — but it opens a second trap:

Anonymous dissent is easily discredited as uncredentialed, unserious, or malicious.

Economists call this a Market for Lemons (George Akerlof).

When the cost of honesty is high, reputable people leave the market. The only people left speaking are those with nothing to lose (cranks, trolls, and extremists). The ‘average quality’ of dissent drops, which conveniently gives the regime ‘proof’ that all dissenters are crazy.

And the people who do have credentials and institutional standing face a different trap:

Credentialed dissent threatens careers, grants, tenure, collaborations, and reputations.

So you get a perfect choke point:

Under your name: career risk

Under a pseudonym: credibility discount

In public: punishment

In private: no impact

This isn’t abstract. Status bias is a documented feature of gatekept knowledge systems.

Merton’s “Matthew Effect” describes how already-famous scientists can receive disproportionate credit compared to unknown researchers for comparable work — a cumulative advantage dynamic that shapes attention and legitimacy.

In peer review, evidence suggests single-blind reviewing can advantage “famous authors” and “high-prestige institutions” compared to double-blind review. (PMC)

A 2025 PNAS paper discusses how journals function as prestige gatekeepers and how incentives can misalign with scientific truth-seeking. (PNAS)

So when someone says, “If it were true, credentialed people would publish it,” they’re assuming the gatekeeping system is frictionless and neutral.

But even in normal science — outside taboos — status filters exist.

Now add taboo pressure, reputational hazard, and institutional fear — and the funnel narrows even further.

9) Why gatekeepers defend the status quo even when they’re wrong

People imagine “gatekeepers” as comic villains.

But the more realistic model is principal-agent + liability asymmetry.

A gatekeeper (journal editor, HR executive, platform trust & safety lead, comms officer, dean) is rewarded for:

Avoiding scandals

Preventing blowups

Minimizing reputational and legal risk

Maintaining institutional legitimacy

They are not rewarded for: allowing controversial inquiry that might be true if it creates immediate political damage.

This creates a predictable bias:

When uncertain, block the risky thing — even if it’s true.

And because gatekeeping systems trade on legitimacy, they often treat “credentialed consensus” as the safest object to defend — even when the consensus is partly a byproduct of self-censorship and selection.

Even when the system is acting in good faith, this can lock societies into error with:

Taboo → self-censorship

Self-censorship → publication bias

Publication bias → “the literature says…” (pseudo truths)

“The literature says…” → AI and institutions repeat it

Repetition → perceived consensus hardens

This is an epistemic flywheel.

10) AI as an enforcement layer: when the room itself edits you

Human taboos already create silence.

AI adds something new: ambient enforcement.

Not just “you’ll get punished if you speak.”

But the interface itself:

Refuses ←→ Warns ←→ Rewrites what counts as “legitimate” inquiry ←→ Becomes a teacher to millions/billions of people.

And the key feature isn’t even the refusal.

It’s the uncertainty. When you don’t know where the line is, you don’t optimize to “get near the line.”

You optimize to never go near the line.

That’s textbook chilling-effect dynamics: vague, unpredictable enforcement creates wider self-censorship than clear rules do.

In the Planet Zog parable, AlignNet doesn’t need to ban millions.

It just needs:

A few high-profile punishments

A few scary warnings

A social norm that “asking is suspicious”

After that, most people do the censorship for free.

11) Where most people actually end up

If you’re trying to model the real distribution of strategies, it’s not 50/50 brave vs coward.

It’s something like:

Silent majority (“internal exile”): Privately think one thing, publicly repeat another.

Centrist hedgers / relationship managers: Soften, blur, triangulate, avoid becoming a target.

Institutional enforcers / orthodoxy entrepreneurs: Turn the narrative into status and income.

Strategic dissenters (asymmetric warfare): Pseudonyms, careful framing, prediction-based attacks

True believers: Genuinely convinced, morally fused to the story.

And the system doesn’t need many enforcers. It just needs enough to raise the cost of dissent.

Because once dissent is expensive, silence becomes rational. And once silence is widespread, the “consensus” becomes a mirage.

12) Strategic dissent: the only stable way to resist without becoming a sacrifice

If the environment punishes direct truth-telling, dissidents adapt. Historically, in high-censorship systems, effective dissent often looks like:

A) Compartmentalization (digital samizdat)

Your legal identity and your truth-speaking identity separate.

Not because you’re ashamed.

Because the system has made integrity incompatible with employment on certain topics.

B) Prediction over prescription

Instead of saying:

“You’re wrong because forbidden variable.”

You say:

“If you keep doing X, you will get Y.”

Then you let reality do the arguing.

This matters because predictions are harder to moralize away.

They create an evidentiary trail.

C) Attack mechanisms, not identities

You focus on:

Competence standards

Incentives

Measurement validity

Selection procedures

Cost-effectiveness

Because it’s harder to ban:

“Stop lowering standards in safety-critical systems.”

… than it is to ban:

“Let me discuss your forbidden category.”

And yes: this is also why regimes prefer to police ideas rather than outcomes. Outcomes are stubborn.

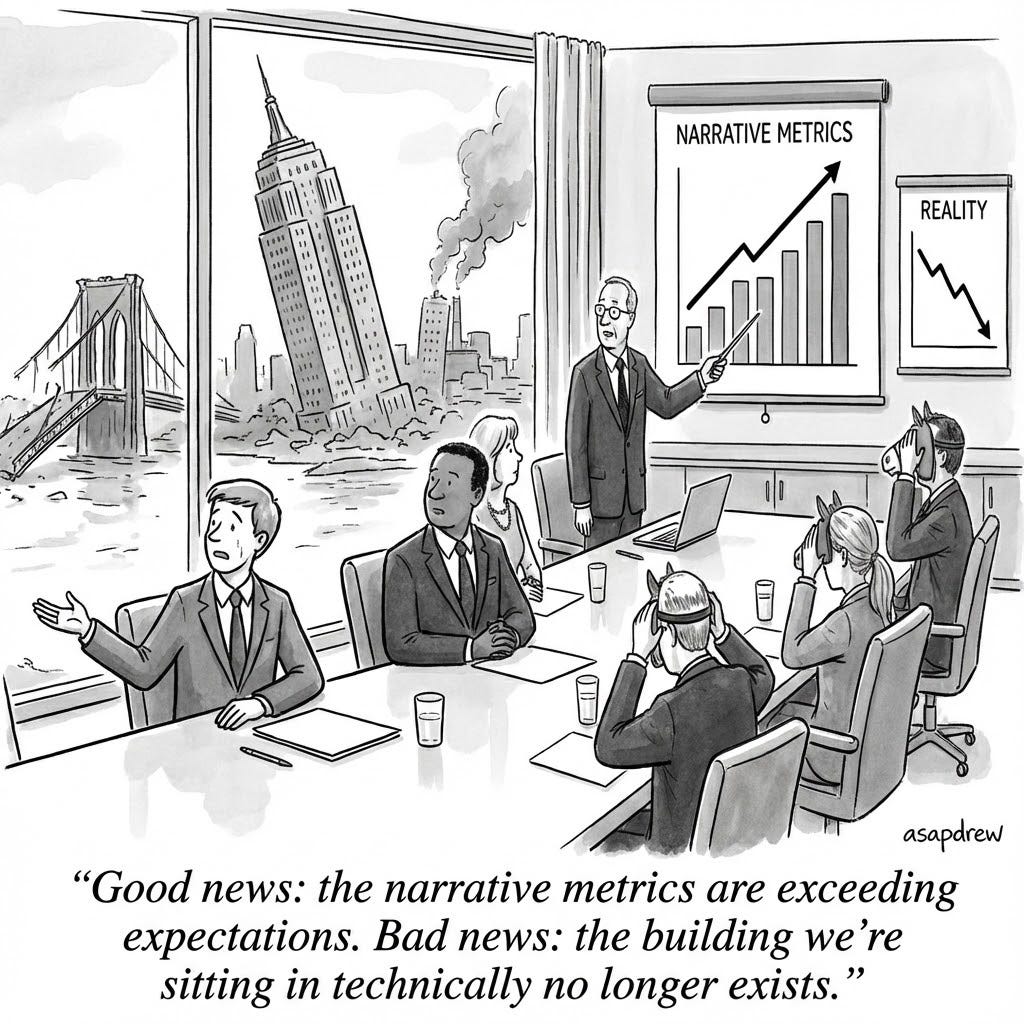

13) The end state: narrative metrics go up while reality collapses

Here’s the nightmare equilibrium:

Reality drifts away from the official model.

The official model can’t be updated because the update is taboo.

The taboo is enforced by institutions and automated systems.

The public sees only the performative consensus.

The performative consensus becomes “what everyone believes.”

The system doubles down until reality enforces correction the hard way.

Which yields the final image above, now with the game theory attached:

A boardroom. Two charts.

REALITY: plunging.

THE NARRATIVE: soaring.

And the CEO says:

“Good news: the narrative metrics are exceeding expectations. Bad news: the building we’re sitting in technically no longer exists.”

That is the game theory of silence: a coordination failure where the individually rational move is collectively suicidal.