Most Women Aren't Dehydrated: A Tiny "Mild Dehydration Affects Mood" Study Wildly Overextrapolated

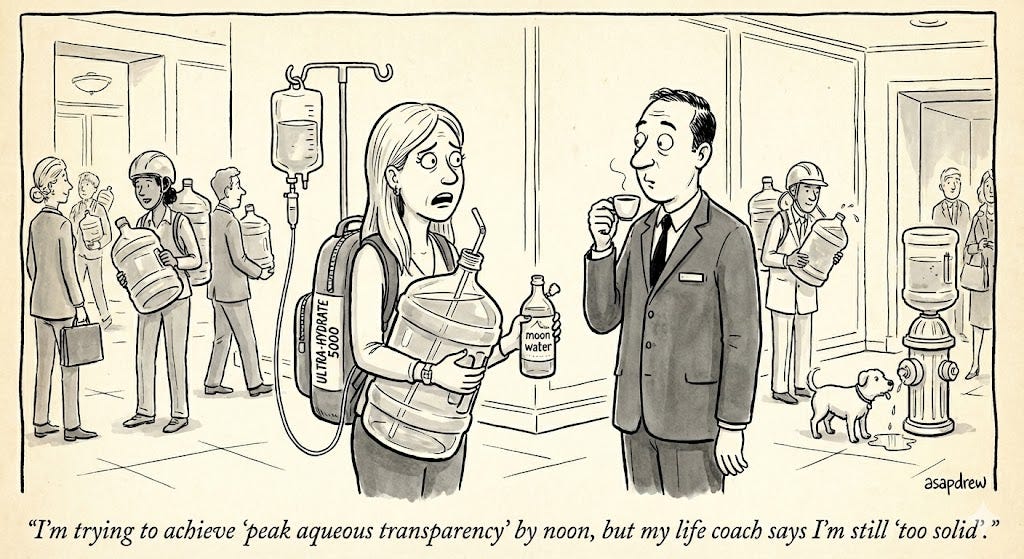

Populist grifters running amok with a pathetically weak study to make claims about hydration in women that have no basis in reality.

Was recently browsing “X” and saw an older study “Mild Dehydration Affects Mood in Healthy Young Women” (2012) trending… getting spammed across the timeline.

Populist grifters latched onto this relatively pathetic, throwback study to extrapolate findings (i.e. imply things) in ways that are downright idiotic.

The (il)logic of your average populist moron is something like:

Many people are dehydrated and women especially are dehydrated: This isn’t even true. Most people self-regulate (drink when they feel thirsty… stop drinking when they aren’t thirsty) and this works remarkably well to maintain healthy physiologic homeostasis.

Everyone needs to hydrate more! Dehydration is impairing cognition, mood, etc.: Many people think that hydrating “more” yields profound health benefits. The logic is something like: (A) overhydration is beneficial relative to status quo (normal hydration) and/or (B) many people/women are mildly-to-moderately dehydrated (such that they need to drink more water).

IYKYK: Only my in-group knows… scientists and normies are too stupid to understand the truth… we are smarter than everyone. Just wait for the latest research! Hah, owned scientists!

This same health populism (i.e. Facebook soccer mom “Did my own research” reading the best science from other Facebook soccer moms’ who did their own research reading the lone grifting scientist who confirms what they wanted to believe in the first place) (il)logic is routinely used to debate COVID vaccines, seed oils, autism, “artificial” ingredients, GMOs, fluoride, etc.

There is a massive scientific (il)literacy problem and sadly the morons don’t realize they are the morons… they think they have special insight that experts don’t want them to know about or that mainstream science is behind the times and will “catch up.”

And many smart people love blaming the scientists for “poor communication” and messaging re: why the average person doesn’t understand things. The blunt reality is that even with PERFECT COMMUNICATION… these things would not sink in.

You are dealing with a combination of: (1) low IQs and (2) strong emotion (polarization) in the general population… and there are certain things they just don’t accept.

Feelings don’t care about your facts!

So I’m going to break down why this study is basically “junk science” such that the findings are mostly worthless information.

1.) Mild Dehydration vs. Mood in 25 Healthy Young Women (2012)

Armstrong et al., “Mild dehydration affects mood in healthy young women,” Journal of Nutrition, 2012. (PubMed)

The abstract gets spammed everywhere, so here’s the key design and result in plain language.

Who was studied?

25 women

Average age: ~23 years

Healthy, physically active

All on oral contraceptives (to control hormone variation)

This is an EXTREMELY TINY and ULTRA SPECIFIC SAMPLE of women… not your “average woman.”

Young women, all healthy/physically active, all on oral contraceptives… and there were only 25!

What did they actually do?

Each woman spent three separate 8‑hour days in the lab. The sample of only 3 days is also short but good enough to determine a simple/general effect.

On each day, the sample:

Walked on a treadmill 3 times (40 minutes each) at a moderate pace.

Was kept in a warm lab environment (no icy air‑con chill here).

Experienced one of three hydration conditions:

DN (dehydration, no diuretic):

Exercise‑induced sweat loss

No fluid replacement allowed (except tiny disguised sips)

DD (dehydration + diuretic):

Same exercise

40 mg furosemide (a loop diuretic) to make her pee more

Again no fluid replacement

EU (euhydration):

Same exercise

Placebo pill

All sweat/urine losses fully replaced with mineral water

Throughout the day they measured:

Body mass (to estimate fluid loss)

Serum osmolality (blood concentration, a hydration marker)

A battery of cognitive tests

Mood (Profile of Mood States, POMS)

Symptoms: task difficulty, trouble concentrating, headache, etc.

Then they pooled all the DN and DD time‑points where a woman had lost ≥1% of her body mass and compared those to the matching EU time‑points. Average “mild dehydration”:

–1.36 ± 0.16% of body mass (≈ 0.8–0.9 L for a 60–65 kg woman).

What changed?

Cognitive performance: “Most aspects of cognitive performance were NOT affected by dehydration.”

Mood (POMS)

Vigor–activity: lower when dehydrated

Fatigue–inertia: higher when dehydrated

Total mood disturbance (TMD): higher

Symptoms: Higher ratings of task difficulty, concentration problems, and headache on 0–10 scales.

So yes, when these women were deliberately under‑hydrated during a hot-ish, treadmill‑heavy lab day, they reported:

A bit less energy, a bit more fatigue, a bit more “this feels hard,” and a bit more headache.

That’s the core result. Common sense stuff.

2.) Why this study is basically junk…

The conditions in this study were nothing like normal life, there were many confounding variables, and the effect sizes (magnitude of effects) were tiny.

A) The conditions are nothing like ordinary life

In real life:

You move around at varied intensities.

You drink when you’re thirsty.

You eat food (also water).

You’re not usually in a controlled warm chamber with scheduled treadmill marches and banned from refilling your bottle.

In the study, “mild dehydration” was caused by an ENTIRE DAY of structured exercise plus fluid restriction (plus a diuretic in one arm).

This is forced dehydration, not “oops I forgot to drink a glass of water this afternoon.”

And you don’t even need any exotic “brain drying out” story to explain most of the results: just being uncomfortably thirsty is distracting and annoying.

If I lock you in a warm room, march you on a treadmill three times, and tell you you’re not allowed to drink, of course you’re going to rate tasks as harder, your concentration as worse, and your head as a bit more “off.”

That’s a perfectly normal response to discomfort and thirst, not special evidence that “mild chronic dehydration wrecks women’s brains.”

Also worth stressing: they don’t just “compare hydrated vs dehydrated days.”

They:

Force dehydration with three warm‑room treadmill bouts + fluid restriction + sometimes a diuretic, and then

Only analyze data points where a woman has already hit ≥1% body‑mass loss.

In practice that means their “dehydrated” data mostly come from the later, most fatiguing parts of the day.

Early‑day measurements that didn’t hit 1% are thrown away. So “dehydrated vs hydrated” is tangled up with time‑of‑day and accumulated fatigue by design.

B) Lots of confounds, very little clean signal

What changed between hydrated and dehydrated conditions?

Heat strain (warm lab + exercise)

Fatigue from repeated treadmill bouts

Possibly the diuretic’s side effects (GI feel, needing to pee earlier, etc.)

The obvious subjective experience of “today they keep giving me water vs today I’m dry and thirsty”

There’s also a sneaky drug confound: one of the “dehydration” days included 40 mg furosemide (Lasix). The authors show DN (exercise‑only) and DD (exercise + diuretic) end up with similar average body‑mass loss and serum osmolality, then pool them together as one big “mildly dehydrated” condition.

That might be fine for water balance, but it completely blurs any specific effects of the drug (electrolyte shifts, blood‑pressure changes, how it feels to be pharmaceutically diuresed) into the “dehydration” bucket.

We simply don’t know whether Lasix itself nudged mood or symptoms, because they never separated it out.

They also claim they “avoided confounding heat stress,” but their own numbers say otherwise. In the dehydrated condition:

Core temperature was ~0.3°C higher (both after exercise and at rest right before the cognitive tests)

Heart rate was ~9 bpm higher after exercise

They brush this off as “minimal,” but anyone who’s ever been even slightly hotter and more tachycardic than usual knows it doesn’t feel great. That extra thermal and cardiovascular strain by itself can make you feel more tired, irritable, and headachy — even if hydration were magically identical.

All of these can worsen mood and headaches even if hydration status were identical. The study design does not cleanly separate “water deficit” from everything else going on.

On top of that:

Sample size is small (n=25) and highly selected.

They run dozens of statistical tests: six POMS subscales + total mood score + 3 symptom VAS at rest and during exercise, plus all the cognitive metrics.

They use the usual p ≤ 0.05 cutoff with no correction for multiple comparisons. Purely by chance, some p‑values will pop under 0.05. That’s exactly what you see: a handful of mood/symptom scores squeak through; most things don’t move.

When you strip this down, the most you can honestly say is:

“Under these exact lab conditions, at about 1.3% body mass loss, these 25 young, fit women reported feeling somewhat more tired, headachy and unfocused than when well‑hydrated.”

That’s not necessarily useless… just confirmed common sense (most would assume that dehydration after exercise would cause some issues). This is miles away from “mild dehydration wrecks your mental health in daily life.”

C) Effect sizes are modest, not dramatic

The full paper gives actual POMS scores; the differences are a few points on scales that are 0–28 or 0–60 wide. PainScience’s commentary captures this well:

“This research… supposedly shows that surprisingly mild dehydration can make you a bit pissy and headachy… if the effect on mood is significant, we are probably also thirsty … and if we’re not actually thirsty, the effect is probably pretty minor.” (PainScience)

This is where percentage‑talk gets downright clowny. Example: headache VAS goes from 1.1 to 2.3 on a 0–10 scale. In relative terms that’s a 109% increase — sounds terrifying!

In absolute terms you’ve gone from “barely noticeable” to “mild annoyance.” Same thing on POMS:

Fatigue goes from ~14.6 to 17.1 on a 0–28 scale: a 17% relative jump that’s actually +2.5 points, i.e. roughly ⅓ of a response step per item.

Total mood disturbance goes from 46.6 to 55.4 on a –30 to 200 scale: an 8.8‑point shift in a 230‑point range.

So yes, things shift in the statistically “worse” direction. But the magnitude is tiny. Huge % changes on tiny baselines are the oldest trick in the PR book.

But when this hits news releases and “Hydration for Health” marketing, it morphs into:

“Mild dehydration has important mood and cognitive effects.”

The jump from “slightly worse POMS score under forced dehydration” to “big practical everyday mood impact” is pure spin.

D) Industry fingerprints all over it

Armstrong’s study was funded and promoted by Danone Research (bottled‑water giant).

Armstrong and co‑authors are featured on Danone’s “Hydration for Health” site; one author sits on their scientific advisory board. (Hydration for Health)

The Hydration for Health summary even claims:

“Most adults reach this level of dehydration [~1.3–1.6% body mass loss] one or more times during the course of a week.”

That’s speculative marketing, not something the actual paper demonstrated.

Funding alone doesn’t invalidate results, but when:

The design exaggerates differences,

The effects are small and subjective,

And the conclusion is perfectly aligned with “everyone should drink more water (preferably bottled)”…

The “Discussion” section then wanders off into pure speculation: they suggest their data “support” a hypothesis that fluid shifts might contribute to PMS mood changes — even though they only tested women on the pill, always in the same placebo‑pill window, with zero menstrual‑phase comparison.

They also hand‑wave that “healthy females may lose only 1.36% of body mass during daily activities” if not “actively hydrating”… despite never following anyone in a real‑world setting. This is storytelling layered on top of a narrow lab protocol.

E) Nerd‑level limitations (bonus)

If you really want to see how fragile this paper is, here’s the short version:

Tiny, ultra‑specific sample: 25 women, all ~23 years old, healthy, physically active, all on oral contraceptives, all tested in the placebo week of their pill cycle. No men, no older adults, no natural cycles, no chronic illness. One university lab.

Weird timing: Each woman did the three conditions ~28 days apart. It’s a crossover, but life doesn’t freeze for 3 months: stress, sleep, training etc. can all drift.

Heavily trained on the tests: They came in for 3–5 practice sessions until their performance plateaued. That gives you polished task‑monkeys, not everyday cognition. If anything, it makes the lack of cognitive impairment at 1.36% body‑mass loss more telling.

Forced, artificial dehydration: Warm environmental chamber, three 40‑minute uphill treadmill bouts, strict fluid restriction in two conditions, and a loop diuretic in one of those. This is not “forgot my water bottle this afternoon.”

≥1% cut‑off games: For the dehydration days, they throw away any data before a woman hits 1% body‑mass loss and only analyse the sweatiest points. That systematically biases the “dehydrated” condition toward the later, most fatigued part of the day.

Pooling diuretic + non‑diuretic trials: Exercise‑only dehydration (DN) and diuretic + exercise (DD) get merged into one “dehydrated” bucket because average osmolality and body‑mass change happened to match. Any drug‑specific or electrolyte effects are now impossible to tease apart.

No electrolyte data: They measure serum osmolality but not sodium/potassium etc., so we can’t even say “this is pure water loss with normal electrolytes.”

Residual heat / HR differences: Dehydrated days have higher core temp (~0.3°C) both after exercise and at rest before testing — and a higher heart rate (~9 bpm) after exercise. Those alone can worsen mood and headache.

Mostly self‑report outcomes: The “hits” are POMS mood scores and 0–10 symptom ratings. Objective cognitive performance is essentially unchanged except for a tiny bump in one type of error.

Lots of hypothesis fishing, no multiple‑comparison correction: Dozens of outcomes tested, classic p ≤ 0.05 threshold, a sprinkle of “significant” mood differences that sit right on the 0.03–0.05 edge.

Acute, not chronic: It’s a single‑day acute protocol. They measure short‑term effects under lab stress, then people on X act like it proves anything about “chronic mild dehydration” in normal life.

Industry involvement and spin: Funded and promoted by a bottled‑water company’s “Hydration for Health” campaign, complete with claims like “most adults reach this level of dehydration weekly” that the study itself doesn’t demonstrate.

None of this makes the paper fraudulent; it just means it’s exactly what it looks like if you read it carefully: a tiny, highly artificial, one‑day physiology study showing that forced thirst + a bit of extra heat and fatigue makes people feel slightly crummier.

Turning that into “your depression is probably dehydration” is pure grift or stupidity.

Note: Just because a company (with potential conflicts of interest) sponsors a study does NOT inherently mean the results are automatically inaccurate or misleading, but you should be a bit more skeptical. The worst aspect here is that they claim “most adults reach this level of dehydration one or more times during the course of the week” but they don’t (A) back it up with data OR (B) state for how long this dehydration lasts (could be a blip e.g. ~2 minutes until the person drinks water).

3.) Are most people actually dehydrated?

Short answer: Nope, not according to the best evidence we have.

A) The “75% of Americans are chronically dehydrated” zombie statistic

You’ve probably seen this exact phrase. It’s everywhere—from blogs to clinic posters.

A recent clinical review on adult dehydration puts it bluntly:

“Although mainstream media frequently claims that 75% of Americans are chronically dehydrated, no scientific evidence in the medical literature supports this assertion.” (PubMed)

Yet wellness websites and even some health organizations repeat it as fact.

PainScience traces this claim back to old media segments and netlore, and notes that Snopes has dismissed it as baseless. (PainScience)

So that scary “3 out of 4 people are dried out” number is not from peer‑reviewed research.

And it doesn’t make sense… most Americans have access to water/drinks of all kinds… and they drink whenever they feel thirsty! (Most people aren’t trying to power through days of dehydration as a mental challenge.)

B) What population data actually show

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) set “adequate intake” (AI) values for total water (all foods and beverages) at (National Academies):

3.7 L/day for men

2.7 L/day for women

These aren’t strict minimums; they’re typical intakes of healthy people in surveys.

A CDC analysis of U.S. adults (NHANES 2009–2012) found (CDC):

Men averaged 3.46 L/day total water

Women averaged 2.75 L/day

So on average:

Men are just a bit under the AI.

Women are basically right at it.

Older adults and some subgroups drink less, which matters (more on that in a second). But the claim that most healthy young and middle‑aged adults are way under basic needs just doesn’t match this dataset.

C) Thirst and self‑regulation actually work

The IOM’s own summary is famous for this line:

“On a day-to-day basis fluid intake, driven by the combination of thirst and the consumption of beverages at meals, allows maintenance of hydration status and total body water at normal levels.”

The 2010 U.S. Dietary Guidelines echo it:

With regular access to beverages, healthy individuals generally have adequate total water intake; the combination of thirst and typical drinking behaviors is sufficient.

Heinz Valtin’s classic paper digging into the “8×8” rule reached the same conclusion:

There is no scientific evidence that everyone needs 8 glasses of plain water a day.

Surveys of thousands of adults show they drink less than that and remain healthy.

Caffeinated drinks and even mild alcohol count toward total fluid.

In other words: for healthy adults with free access to fluids, your body’s water balance systems are good at their job.

D) Who is at genuine risk of dehydration?

Where dehydration really is common and serious:

Older adults

Prevalence estimates: 17–28% in U.S. older populations. (PubMed)

Reasons: blunted thirst, mobility issues, chronic diseases, medications, sometimes poor access to fluids.

Hospitalized or institutionalized patients

Dehydration is a frequent cause of admission and can worsen a lot of conditions. (PubMed)

Specific situations

Heavy sweating in heat, vomiting/diarrhea, acute illness, very high‑intensity work or sport without fluid access.

These are the groups that need proactive hydration strategies… not the average office worker with a coffee and a water bottle at arm’s reach.

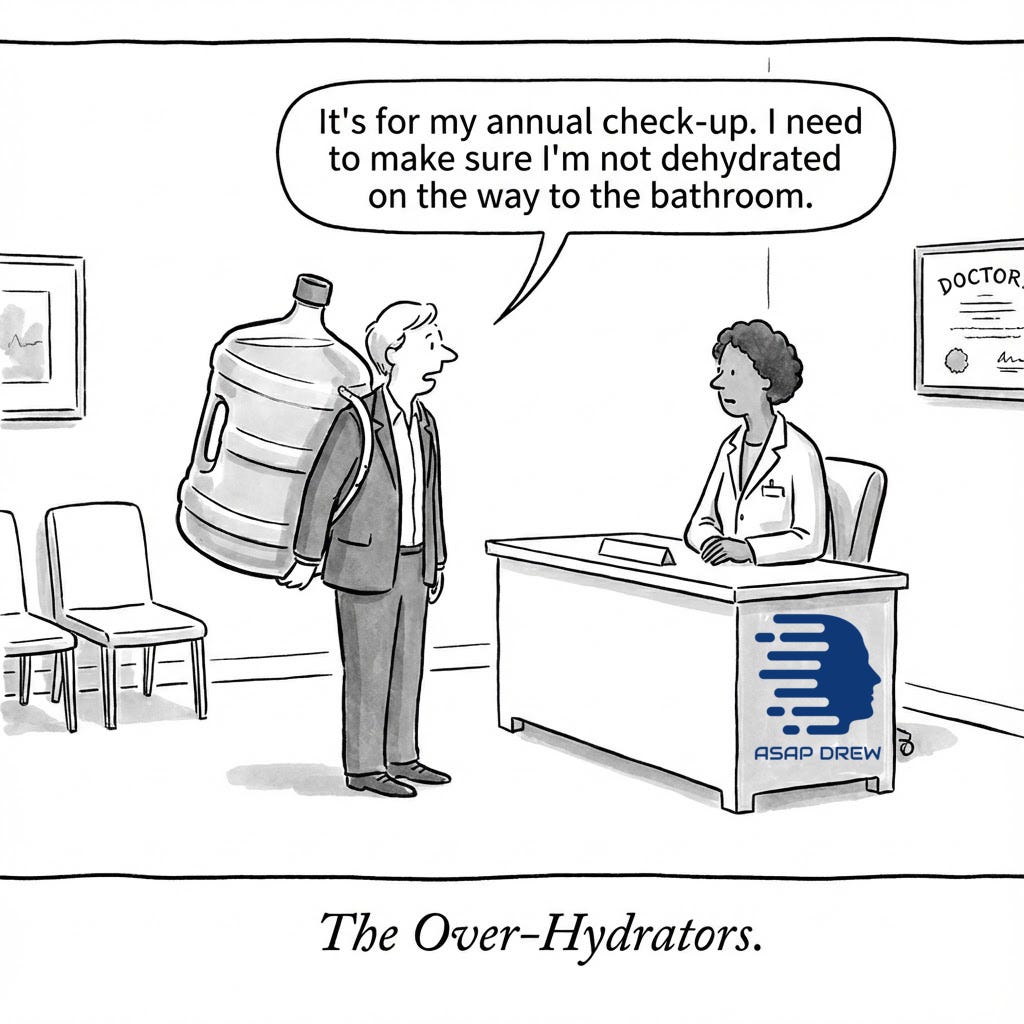

4.) The other side of the coin: overhydration and hyponatremia

Drinking too much water is NOT harmless. There is a sweet spot. If you are constantly peeing (clear pee all day), you are overhydrating.

If the overhydration is significant, you may develop hyponatremia — an electrolyte imbalance resulting from low sodium… and in serious cases this can be fatal.

It’s also difficult to stay focused/productive if you have to run to pee every 10 minutes because you’re guzzling down water like a parched camel.

A) What is hyponatremia?

Hyponatremia = low blood sodium (below about 135 mmol/L). In severe cases, brain cells swell → headache, confusion, seizures, coma, death.

One major cause is overdrinking hypotonic fluids (plain water or low‑sodium sports drinks) faster than the kidneys can excrete, especially when stress hormones are suppressing urination. (Harvard Gazette)

B) How does this show up in the real world?

Endurance sports are the classic example:

The landmark NEJM study on Boston Marathon runners reported that exercise‑associated hyponatremia (EAH) occurred in a “substantial fraction” of non‑elite runners, and was strongly associated with weight gain during the race—i.e., overdrinking. (PubMed)

A recent review puts EAH incidence from large races in the 7–15% range, depending on how you define “case” and on race conditions. (MDPI)

Harvard’s summary of Arthur Siegel’s work spells it out: for slower marathoners, “overhydration is more dangerous than dehydration”; they explicitly warn against constant aggressive drinking. (Harvard Gazette)

And then there are the horror stories we occasionally hear:

Water‑drinking contests gone wrong.

People with compulsive drinking behaviors.

Well‑intentioned folks chugging massive volumes for “detox.”

They’re rare in the general population, but they are almost always fueled by the idea that “you can’t have too much water”—which is false.

C) Everyday downsides of over‑hydration

Even without hyponatremia, overdoing it can still suck:

Constant peeing, including at night (nocturia) → disrupted sleep.

Always needing a bathroom, which is a real problem in certain jobs or for people with bladder issues.

For some people, electrolyte dilution and low sodium symptoms (mild headache, nausea) long before anything shows up in labs.

Again: not saying “never drink water.” Just that more is not always better.

5. So what can we reasonably say about mild dehydration and mood?

If we zoom out from just Armstrong 2012 and look at the broader literature:

Severe dehydration (e.g., 3–4% body mass loss, high heat, hard exercise) definitely impairs performance and feels awful.

Mild dehydration (≈1–2%) under stressful conditions (heat, long exercise, sleep deprivation) can modestly worsen mood and perceived effort, and sometimes certain cognitive tasks.

Effects are small, variable, and context‑dependent. They’re not the difference between “fully functioning human” and “emotional wreck.”

It’s perfectly sensible to say:

“If you’re training hard, working in the heat, or prone to headaches, paying attention to fluid intake (and sometimes electrolytes) is useful.”

It is not sensible to say:

“Healthy people living normal lives are chronically dehydrated, and that’s why they’re depressed, anxious, or unfocused.”

That leap goes way beyond the data.

6. A sane, non‑hype way to think about hydration

Here’s a framework that respects physiology and reality.

A) Trust your built‑in regulation (most of the time)

If you’re:

A generally healthy adult

In a temperate environment

With normal kidney function and access to food and drink

…then the combination of thirst + everyday drinking habits usually keeps you in a safe range. That’s explicitly what the IOM and Dietary Guidelines say.

What this looks like in practice:

Drink when you’re thirsty.

Drink more on hot days, with heavy exercise, or when sick.

Include water‑rich foods and beverages: fruits, vegetables, soups, coffee/tea, etc. (All those count toward total water.)

B) Easy self‑checks that don’t require obsession

You do not need an app or a glowing smart bottle.

Some basic cues to follow:

Urine color:

Very dark & strong‑smelling all day → probably under‑doing fluids.

Crystal clear all day → probably over‑doing it.

Pale yellow most of the time = perfectly fine.

How you feel:

Thirst, dry mouth, headache, lightheadedness, fatigue—especially with heat/exercise—are normal cues to drink.

C) If you’re in a higher‑risk group

Consider being more deliberate if:

You’re 65+

You have heart, kidney or endocrine disease

You’re on diuretics or meds that affect water/salt balance

You can’t easily access or remember fluids

You’re doing long endurance events in heat

In those cases, it’s worth talking to a clinician about personalized fluid and electrolyte targets.

The same goes for elite or very serious endurance athletes: they usually benefit from planned strategies rather than just eyeballing thirst.

D) Avoid these common traps

Treating thirst as pathology: Thirst is a normal, useful signal, not a failure state.

Assuming clear pee is the goal: Chronically clear urine usually means you’re pushing fluids harder than you need (will disrupt your focus at work and sleep quality… and could cause hyponatremia).

Believing “8×8” is a medical rule: It’s absolute lunacy to generalize a rule to all people and there is ZERO EVIDENCE to support this blanket prescription in healthy adults.

Ignoring overhydration risks during long events: In marathons and similar events, weight gain during the race is a red flag for overdrinking, not “great hydration.”

7. Bringing it back to that viral study

So when someone drops the Armstrong paper as proof that “everyone’s dehydrated and it’s killing our mood,” here’s the quick pushback:

Tiny, highly specific sample: 25 young, fit women on the pill. Not “all women.”

Artificial protocol: warm lab, repeated treadmill sessions, forced fluid restriction, sometimes a diuretic. Not representative of normal daily life.

Subjective, modest changes: Some mood scales and symptom ratings ticked up a bit; cognition barely changed. The %s are basically meaningless. A 50% increase doesn’t necessarily mean high if the baseline was already minimal.

Lots of confounds & multiple comparisons: Tons of outcomes tested; no correction for that. Some “significant” differences are expected by chance.

Industry context: funded and heavily promoted by a bottled‑water company’s hydration campaign.

Meanwhile:

Actual population data show most healthy adults are near recommended total water intake.

A major clinical review says the “75% chronically dehydrated” claim has no scientific backing. (PubMed)

The IOM literally titled its press release on water intake “Let Thirst Be Your Guide.”

Final thought: Hydration Status in Women & In General

Obviously I am not suggesting hydration status is irrelevant… I’m just saying that if you follow your body’s physiologic “thirst” signal and:

Drink when thirsty

Stop drinking when no longer thirsty

You should be fine. If you exercise hard or have special medical conditions you may need extra water/hydration.

You can use pee color as a “rough guide” (if extremely dark hydrate more, if clear cut back… if normal yellow — you’re probably in a sweet spot).

The “everyone is dehydrated and doomed” narrative is mostly just bullshit with pathetically cherry-picked supporting “science.”

For most healthy people:

You don’t need to fear mild thirst.

You don’t need to micromanage every sip.

You can overdo water, and you don’t get bonus points for living on the toilet.

Drink when you’re thirsty, drink more when conditions demand it, and ignore anyone trying to sell you the idea that your perfectly functional thirst mechanism is broken.