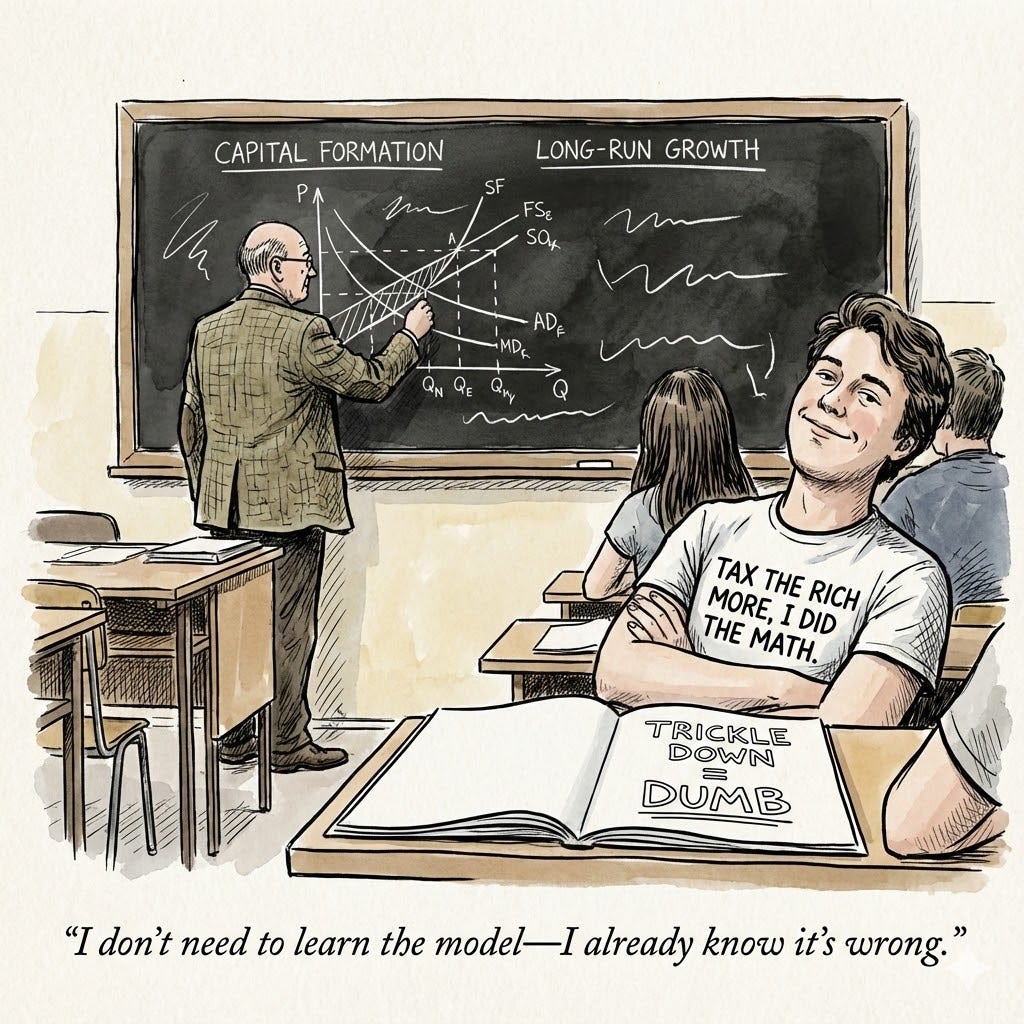

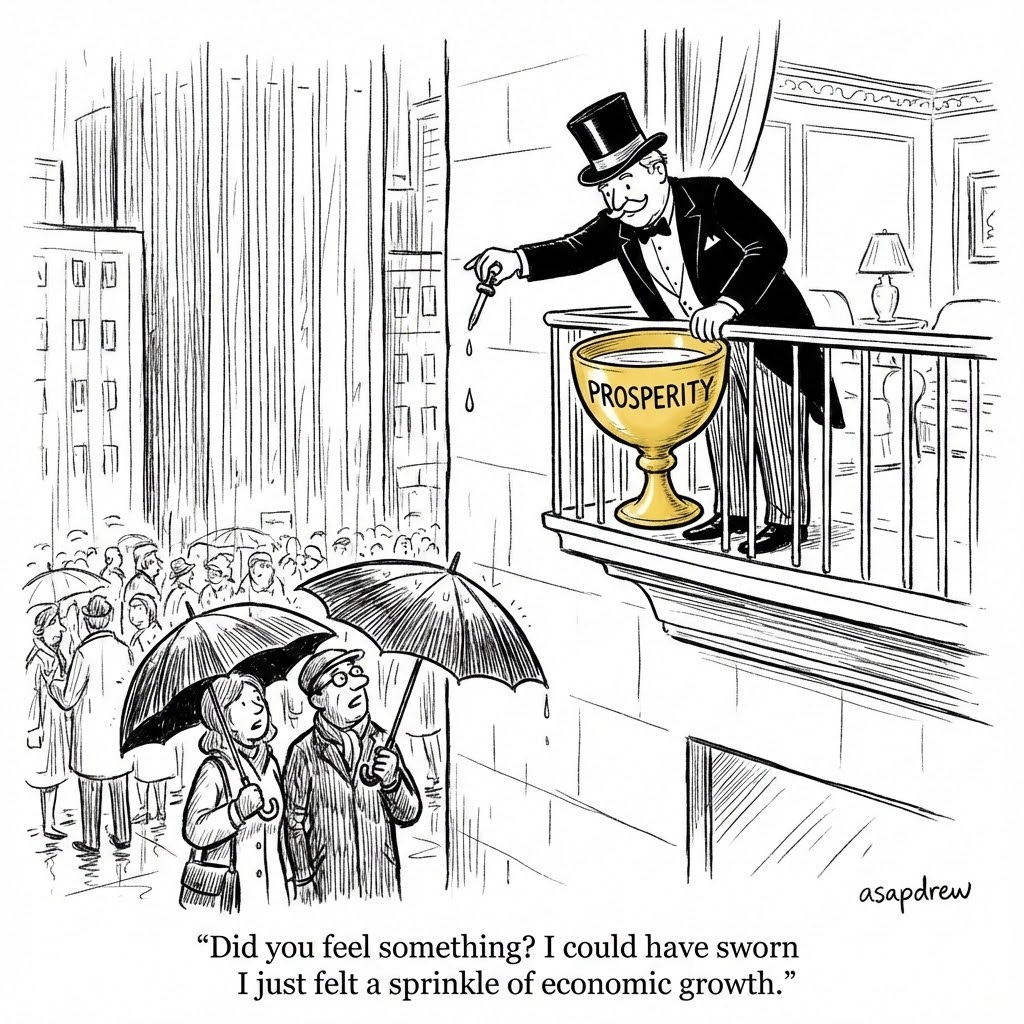

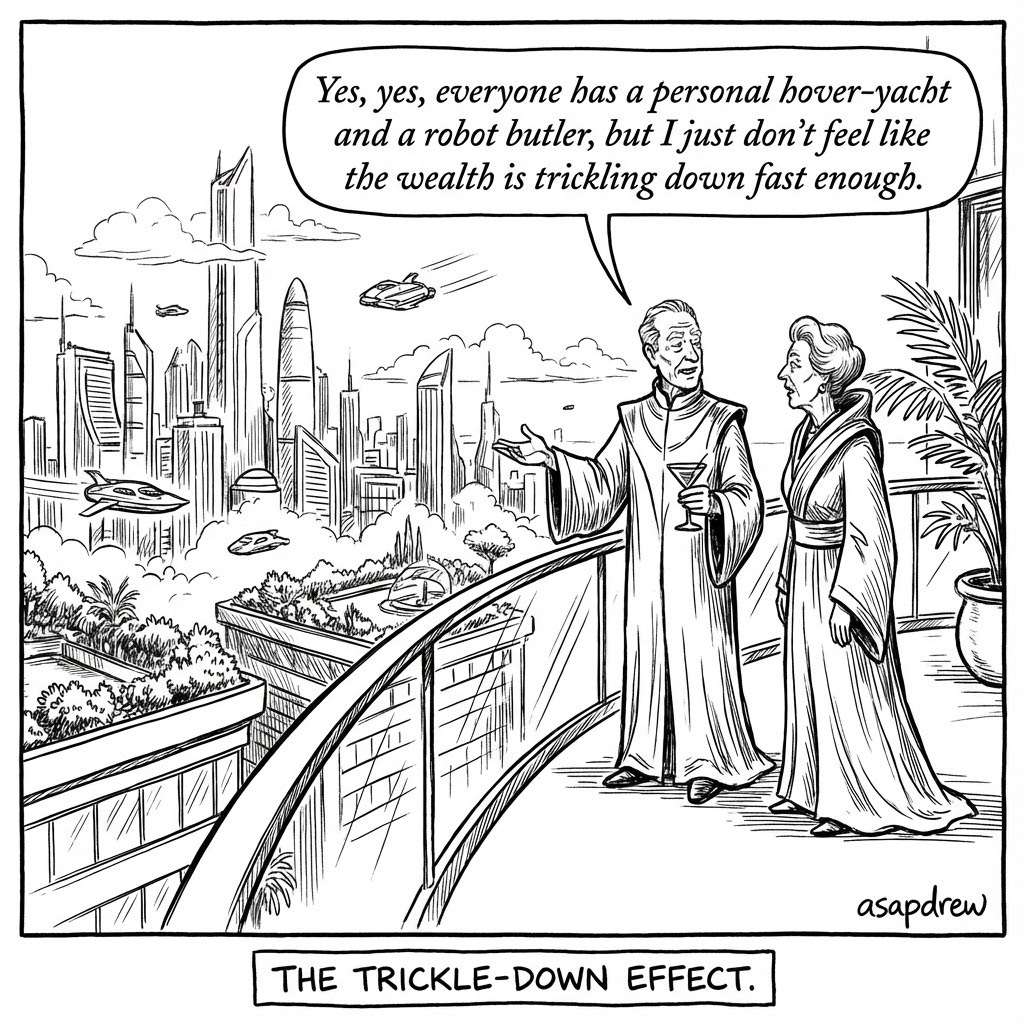

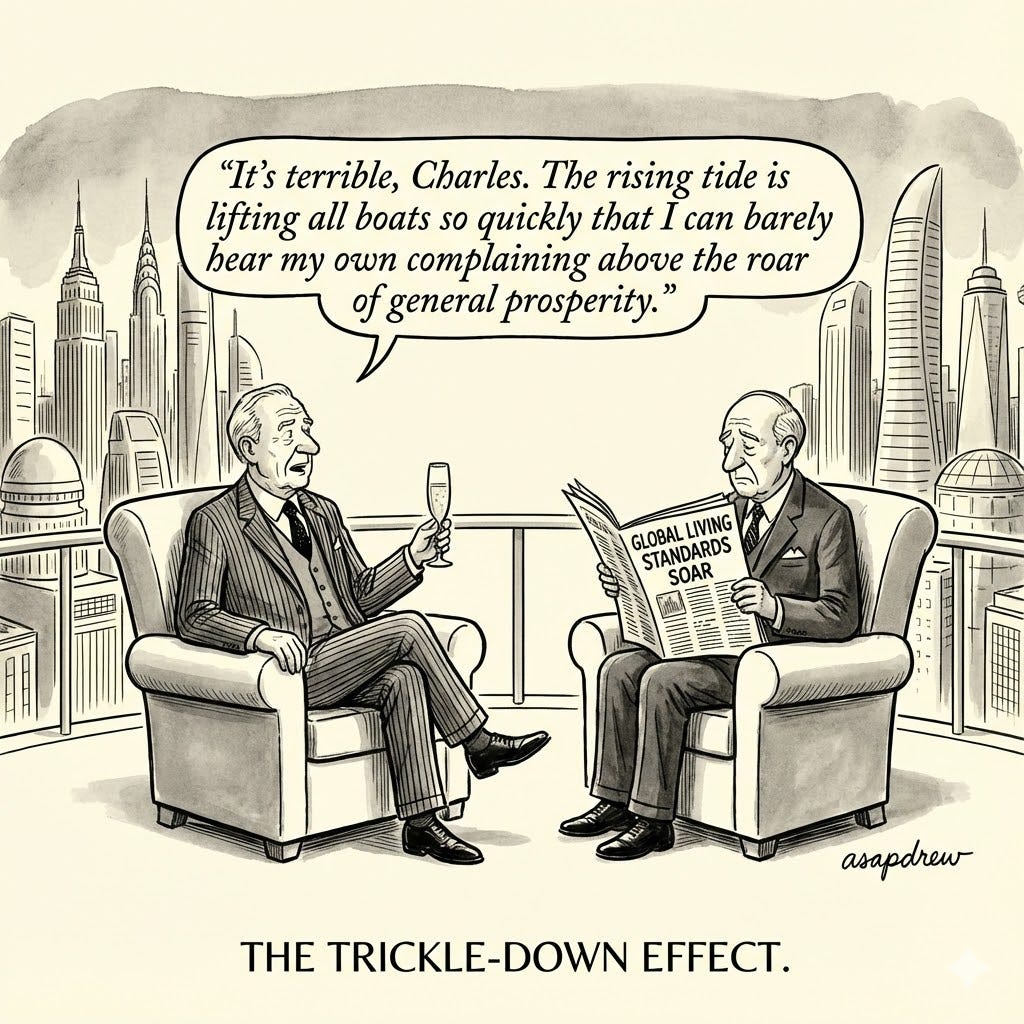

There are often social media jousts re: whether “trickle-down economics” works.

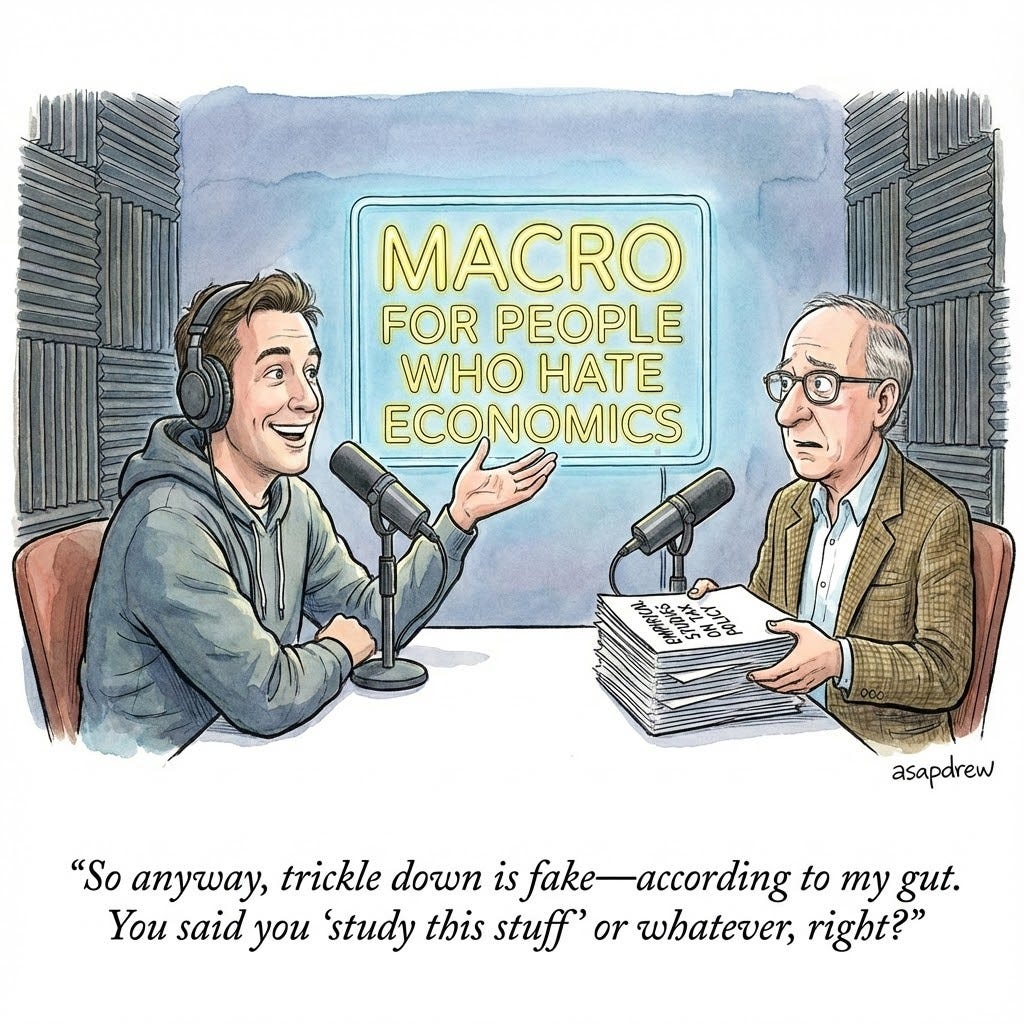

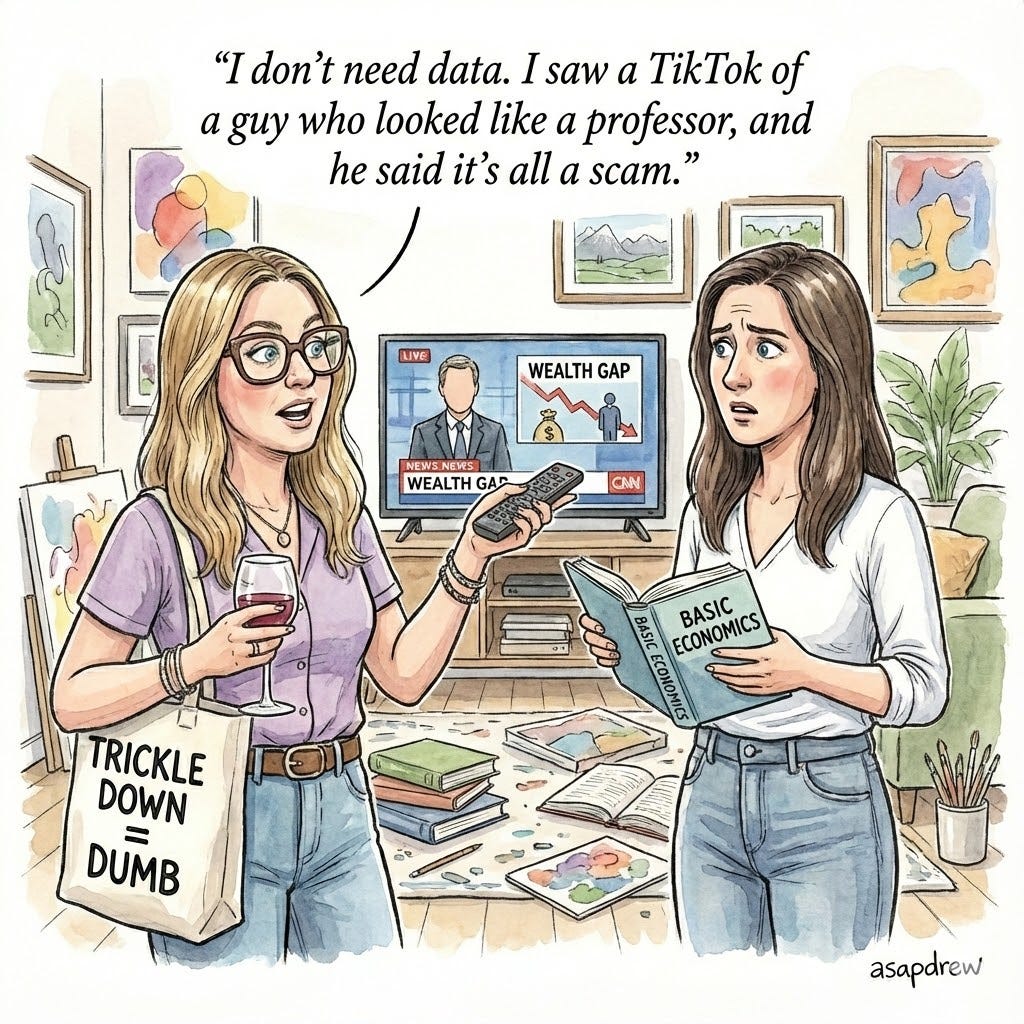

Most people are mentally checked out if you don’t immediately take a polarizing stance (without clarification of what “works” means)…

Yes it works (a random rich guy perceived as Scrooge McDuck swimming laps in a liquid-gold LVMH swimming pool)

No it has been extensively debunked (*peer reviewed* by Reddit Wikipedia Bluesky mods)

The reality is that perception of whether trickle-down economics works, mostly depends on your criteria for “works.”

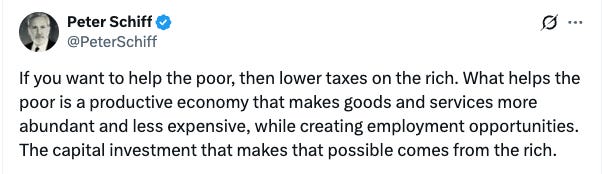

Recently Peter Schiff posted his support for a trickle-down system (without explicitly stating trickle-down economics).

Schiff’s post got ~5.5M views and ~5K likes with 6.3K comments. A lot of views… not many people actually liked what he had to say.

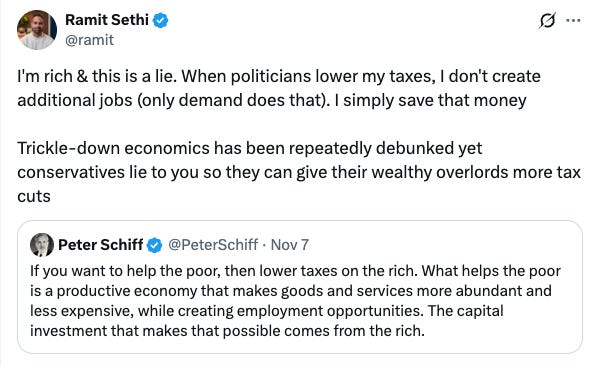

Ramit Sethi, a fairly sensible finance influencer, took the opportunity to dunk on Schiff. This involved a combination of:

A personal anecdote (claiming he doesn’t create additional jobs and is rich… even though he likely does invest some of this money which does help create jobs even if he isn’t personally involved)

A claim that trickle-down economics has been debunked (which isn’t really true but it remains the left-wing populist and “academically correct” perspective)

Sethi’s post got ~3.4M views and ~49K likes with 4.2K comments. Over ~40K more likes than Schiff’s post… which makes sense… it’s an easy position to take.

Why do so many people hate trickle-down economics and love dunking on wealthy people who support it?

Envy & jealousy: They logically know that wealthy people save more money in a trickle-down economic system (lower taxes for the rich… and lower taxes for everyone).

Academics/economists: Told them that trickle-down economics doesn’t work… so therefore anyone who supports it is just flat-out wrong.

It’s really that simple. This is not something most people have thought deeply about.

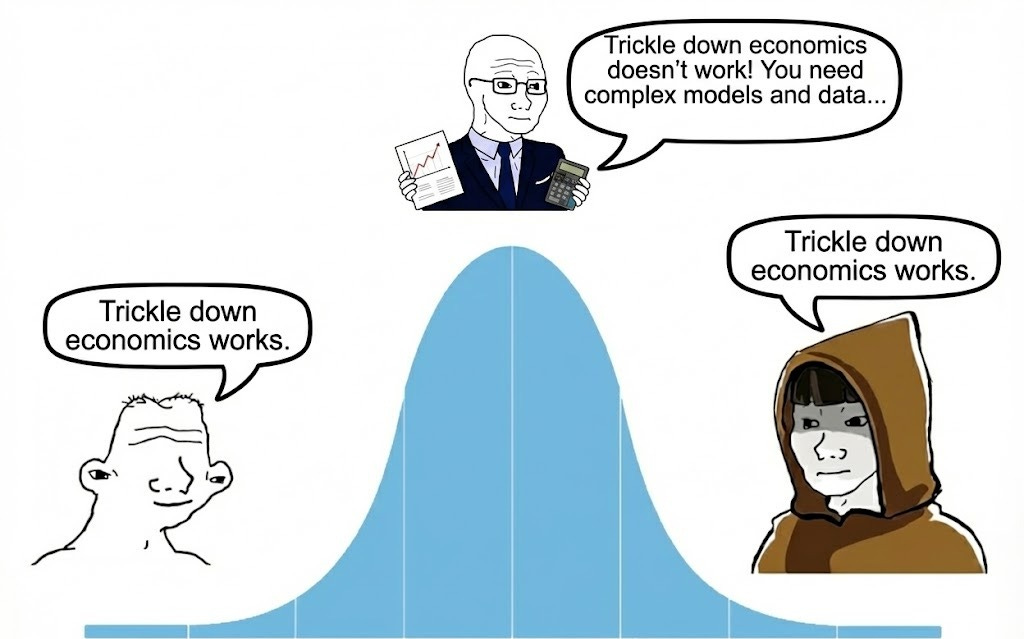

There are basically two tribes in this debate:

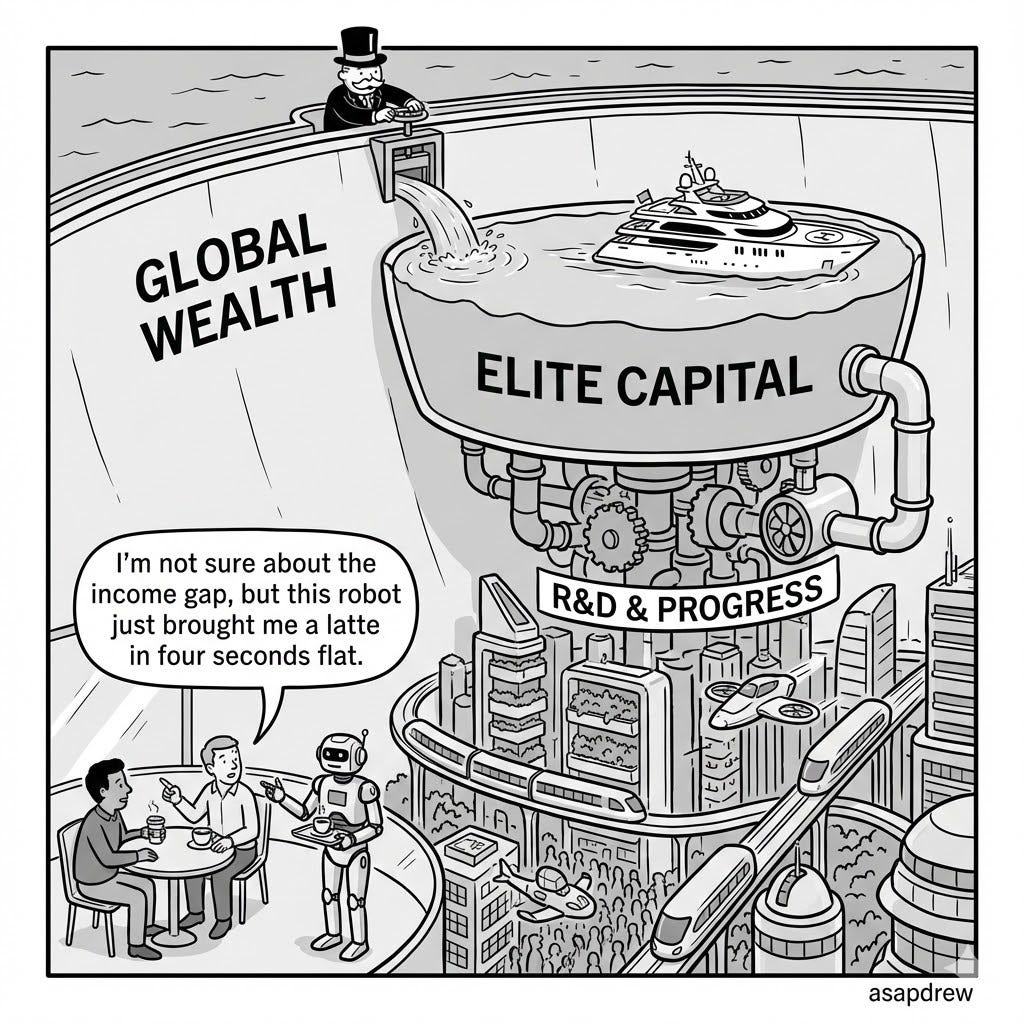

Tribe A (small): Cares about incentives, innovation speed, and rate of improvement in absolute living standards (over the long-term). They ask: “Which system makes everyone richer over the next 30–50 years, even if inequality is high today?”

Tribe B (large): Cares mostly about reducing income inequality today, soothing envy, and giving the median voter a visible short‑term boost funded by “the rich.”

Tribe A looks at trickle‑down / supply‑side systems and says: “Yes, they work — they supercharge innovation and long‑run prosperity.”

Tribe B looks at the same systems and says: “They don’t work, because inequality goes up and the median person doesn’t get a massive, immediate raise.”

I am in Tribe A and will forever take the stance that TRICKLE-DOWN ECONOMICS WORKS… but my criteria for “works” doesn’t involve reducing income inequality… it involves acceleration of innovation and rapid improvement in absolute living standards over a long-term trajectory.

Trickle-down economics is typically viewed as ineffective because it is usually: (1) implemented or measured over a short-term, (2) in a system of government spending (high taxes, high debt, high interest on debt), with (3) excessive regulations. Of course we won’t see much benefit if measuring like this… too many competing confounds and the measurement is misleading.

Current priorities in the U.S. are: (A) government spending (mostly negative ROI, massive debt, high interest on debt); (B) redistribution of resources from productive to unproductive (resulting in more consumption and inefficiency); (C) imposing regulations to prevent free markets/competition OR just to “stick-it-to-the-rich” (as a result of envy or failure to understand reality).

We could “rip the bandage off”… which would mean: (A) gov only spends smartly (necessary, strategic, and/or net positive long-term ROI); (B) flat tax to increase fairness (motivates people to work hard and smart innovators rightfully keep more of what they earn/deserve → allowing them to invest in even more innovation); (C) eliminating most regulations (free competition, no capture).

I believe we could’ve already: cured biological aging, reversed aging, eradicated most biological diseases, terraformed/colonized other planets, customized the human genome, spied on aliens, etc. — but we’re at the mercy of the idiocracy… engaged in the following:

Giving the government money they can waste: Most government spending is inefficient. Can never stop it… it’s a one way full speed freight train. Spending increases every year, people vote for more of it, gov/Fed attempts financial jiu-jitsu… and here we are maintaining a state of fiscal dominance (repressionary tactics to deal with debts).

Redistributing resources from highly productive/innovative people to fiscal net negatives (extractors): Incentives end up fucked up when you tax people so much that they are motivated to leave, demotivated to work hard, and end up with less money to start new projects. If Elon had been in the EU, he’d be fucked… taxed so harshly that most/all of his innovation (e.g. SpaceX, Tesla, Starlink, Boring Co, Neuralink, xAI, et al.) wouldn’t exist… every % you increase taxes takes from an innovator to fund some moronic “feel good” gov project (e.g. High Speed Rail in CA). Not only is it NOT fair to tax people highly, it’s just stupid if you care about accelerating innovation (which improves life for everyone including the poor — at a much faster rate).

Regulating to prevent free markets from solving problems: Oh no! We can’t automate the ports! People will lose jobs! We can’t allow cars — horse/buggy operators will go out of biz! Ban robotaxis… save Uber drivers! Solve global warming! Wait not like that! We need the government to do it! No Elon can’t do it!!! I hate Elon!!! I was diagnosed with Elon Derangement syndrome!! Waaaaaah. Thank god for the Government!! Regulations are so good!!! At least we blocked Elon from building underground tunnels to solve traffic jams!!! Owned! We love spending hours in LA traffic!!!

Trickle-down economics is an ideal sub-component of a system that prioritizes: (A) free markets, efficient gov spending, low taxes, low regulation AND (B) rapid innovation, fairness (equal laws, unequal results), improvement in absolute living conditions for all.

Trickle-down economics does not appear to “work” when selectively measured over a short-term, in a system that prioritizes: (A) high regulation, inefficient gov spending (bloat), high taxes AND (B) egalitarianism, lower income inequality, short-term improvement in relative financial wealth — stemming from the emotion of envy/jealousy.

1. What does “trickle‑down economics” even mean?

Nobody in serious economics writes papers saying “we tested trickle‑down.”

That phrase is a political insult for supply‑side / small‑state capitalism:

Let people keep a large, stable fraction of what they produce.

Make taxes low, simple, and predictable.

Keep regulation minimal and focused on real externalities.

Have a small but competent state that does core public goods (courts, defense, basic infrastructure, some safety net) and not much else.

Accept that inequality will be large, because people, talents, and risk preferences are unequal.

When someone sneers “trickle‑down,” what they usually mean is:

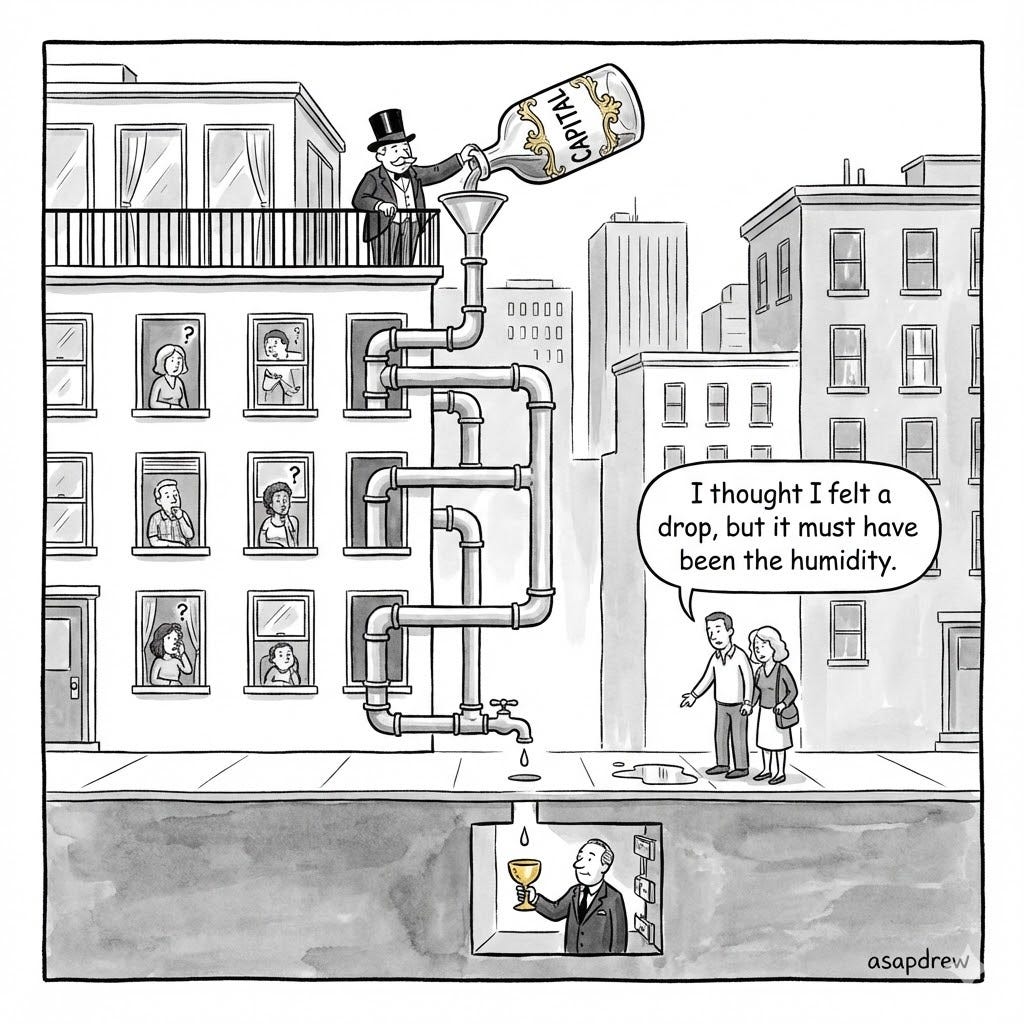

“You think cutting taxes and regulation on the ‘rich’ and on capital leads to more investment, growth, and eventually better living standards for everyone. But the rich just pocket it and nothing trickles down!”

Notice there’s already a bait‑and‑switch here:

They silently assume the goal is:

“Instant, visible gains for the median worker and less inequality right now.”

My goal is different:

“Align reward with contribution; maximize long‑run innovation and living standards. Don’t pretend everyone deserves the same outcome.”

If we can’t even agree on that, of course we’ll disagree on whether something “works.”

So let me be explicit about my criteria:

Fairness = You keep roughly the same fraction of each extra dollar you create, regardless of how productive you are. No extra punishment for being more useful.

Prosperity = We care most about absolute living standards and innovation, not whether the Gini coefficient ticks up.

By those criteria, a supply‑side, low‑tax, low‑regulation system is exactly what you’d design from scratch.

2. Why critics insist “trickle‑down doesn’t work”

It’s easy to dismiss “trickle-down economics” as being ineffective when you have a distorted sample (riddled with confounds) and your definition of “work” is basically just reducing inequality — rather than rapidly accelerating innovation and human development.

A) The flagship evidence critics like

A widely‑cited study by David Hope and Julian Limberg (2020, updated 2022) looks at “major tax cuts for the rich” in 18 advanced economies from 1965–2015. Their headline result:

Big cuts in top tax rates raise the income share of the top 1%

They find no statistically significant average effect on overall economic growth or unemployment.

Popular write‑ups just translate this into:

“Tax cuts for the rich don’t boost growth; they only make the rich richer. Trickle‑down is a myth.”

Fair enough – if you take the study at face value and if “works” means “big, obvious growth boom with no rise in inequality.”

B) Their conceptual model (simplified)

Behind the slogans, here’s how the anti‑trickle‑down story usually goes:

The rich don’t spend the extra money. Their marginal propensity to consume is low. So when you give high earners tax cuts, they save/invest rather than spend. That means weak demand response, weak hiring.

Firms won’t invest just because taxes are lower. If there’s no extra demand, companies use gains for stock buybacks, dividends, or CEO pay. So workers don’t see much benefit.

Rich countries aren’t capital‑starved. The binding constraint is often good projects and demand, not raw savings. So more after‑tax cash at the top doesn’t automatically translate into new real investment.

Inequality itself can hurt growth. If the rich pull further ahead:

The poor may get less education and opportunity.

Politics gets captured by wealthy interests.

Underinvestment in public goods follows.

So, in their mind:

“We cut top rates. We got more inequality, not better growth for the average person. Therefore: trickle‑down doesn’t work.”

Note the structure: the standard they test is “did it reduce inequality and/or create spectacular growth?” Not “did it increase rewards for value‑creation and speed up innovation?”

3. That’s not the system I’m defending

The policies they study are usually:

One more tax‑cut package inside an already large welfare/regulatory state,

with complex carve‑outs and lobbyist‑driven exceptions,

while government keeps spending 35–40% of GDP – or more.

For example, total government expenditure as a share of GDP (OWID):

U.S.: ~36% of GDP

France: ~57% of GDP

Canada: ~42.5% of GDP

Australia: ~37.2% of GDP

That’s not “minimal state, flat/low taxes, simple rules.”

That’s: huge state, and we lower the tax dial a bit here or there.

It’s like “testing” marathon training by doing a warmup jog, eating donuts, and then declaring “running doesn’t make people fit.”

My picture of a trickle‑down / supply‑side system looks closer to:

Government bloat/spending on only logically high ROI investments.

Simple, low, maybe near‑flat taxes that don’t spike at the margin.

Regulation limited to clear, demonstrable externalities, not massive micromanagement of labor, housing, energy, and product markets.

A political culture that accepts unequal outcomes as the price of dynamism. (Equal opportunity, unequal results)

Historically, you see something closer to this in:

Hong Kong, especially pre‑COVID and pre–political clampdown

Early United States, pre–New Deal / Great Society

That’s what I care about evaluating — not “small tweaks to top tax rates in countries already running giant welfare states.”

4. Logic: incentives and the “guarantee”

Now let’s strip away ideology and do first‑principles, game‑theory‑style reasoning.

A) Three basic facts about humans

People respond to marginal incentives. If I get to keep 70¢ of my next dollar of value created vs 40¢, risky effort looks more attractive. That’s especially true for entrepreneurs and high‑skill people: starting a company, working 70‑hour weeks, putting capital at risk is optional.

Risk‑taking is discretionary. No one can force you to:

Hire employees,

Borrow money to build a factory,

Spend 10 years of your life grinding on a startup.

As the state grabs more of the upside and guarantees more of the downside, rational people quietly move to safer, less dynamic paths.

Markets are discovery machines. Prices, profits, and losses are feedback signals. They’re how we find out which ideas create value. If you dull those signals with high marginal taxes and heavy regulation, you choke off experimentation.

So, if you want:

Lots of experimentation,

Lots of capital formation,

Lots of “skin in the game” risk‑taking,

…then you want a system where the mapping from “I create value for others” → “I get rewarded” is as tight and predictable as humanly possible.

B) What “trickle‑down” actually says mechanically

Forget slogans. The real supply‑side claim is:

Lower taxes on work and capital → higher after‑tax return to productive activity.

Higher returns → more effort, more entrepreneurship, more saving and investment.

More capital per worker → higher productivity.

In competitive markets, higher productivity → higher real wages and cheaper, better goods over time.

The only way this doesn’t hold directionally is if you deny one of these:

People respond to incentives.

Capital per worker raises productivity.

Competition pushes gains out to workers and consumers.

If those 3 are true, a lower‑tax, lower‑distortion system must generate more effort, investment, and output on average than a higher‑tax, higher‑distortion one with the same institutions otherwise.

That’s the sense in which it’s “guaranteed to work”: not “guaranteed utopia,” but “guaranteed to be a better engine of innovation and growth than a more redistributive alternative, ceteris paribus.”

5. Fairness: Who is actually paying for whom?

Let’s talk about “parasitic” vs “fair.”

A) Today’s reality: the top heavily subsidize the bottom

Take the U.S.:

Latest IRS‑based analysis: the top 1% of earners pay about 40% of all federal income taxes, while earning about 22–23% of total income. (Tax Foundation)

Overall, the tax system is progressive: one think tank estimate has the top 1% paying a bit over one‑third of their income in total taxes, the middle about 26%, and the poorest fifth about 17%. (ITEP)

On the spending side:

An analysis of federal taxes and transfers based on CBO data finds that for each $1 in federal taxes, the average filer in the lowest income quintile receives about $68 in federal transfers, while the average filer in the top 1% receives about $0.04 in transfers for each tax dollar paid. (AIER)

Take those numbers as approximate rather than divine truth; the exact ratios vary by method. But directionally:

Lower earners are net recipients.

Higher earners are net funders.

This is designed redistribution. It’s not an accident.

B) Government is big… and getting bigger

Total government expenditure (federal + state + local) as a share of GDP is around:

36% for the U.S.

45–55% for many Western European countries (France ~57%)

Historically, that’s completely new.

From 1790 to the early 1900s, U.S. federal spending was usually under 3% of GDP, rising mostly during wars. (EveryCRSReport)

We’ve moved from:

“Tiny federal government that barely cracks 3% of GDP most years”

… to:

“All levels of government together now absorbing more than a third of everything produced, every year.”

If you believe most adults over a lifetime are net recipients once you count direct programs, in‑kind benefits, and hidden subsidies, that’s exactly what you’d expect: a state that large has to take a lot from a relatively small, highly productive group to fund a lot of people who get more out than they put in.

From my fairness standard:

One group carries the fiscal state on its back, while a majority can vote itself benefits from that group. That’s structurally parasitic.

A flat / low tax system with limited spending changes that:

Everyone pays the same marginal rate.

Every extra dollar of spending hits everyone.

You can’t build a stable coalition on “let’s just tax them, not us,” because “them” doesn’t exist.

That’s why, from my perspective, flat taxes + small states are more fair: same rules, same percentage, no extra penalty for being more productive.

6. But does it actually show up in outcomes?

Yes. Especially once you stop looking at tiny tax tweaks and instead zoom out to:

Economic freedom

Long‑run growth

Global poverty

A) Economic freedom and growth

Economic freedom indices (Heritage, Fraser, etc.) try to measure (IoEF):

Small vs big government

Ease of doing business

Trade openness,

Regulatory burden

Property rights, etc.

Recent empirical work consistently finds:

Countries with higher economic freedom tend to grow faster over the long run. (Nature)

One Atlantic Council analysis estimates that a 7‑point increase in economic freedom (on a 0–100 scale) is associated with about 10–15% points higher GDP over five years.

Is that “proof” of causality? No. But it’s exactly what you’d expect if less distortion + stronger property rights + smaller government → better incentives → more capital & innovation.

B) Global poverty and market reforms

Look at the massive arc from 1990 to now.

According to the World Bank:

Around 1990, about 2.3 billion people lived in extreme poverty (≈38% of humanity).

By around 2019–2023, that had fallen to roughly 700–830 million, about 8–9% of the world. (World Bank)

That’s a drop of 1.5 billion people out of extreme poverty in about three decades.

What changed?

Not a global socialist revolution.

Not some giant worldwide welfare state.

Instead:

China moved from hardcore central planning toward market‑oriented reforms and integration into global trade.

India, Vietnam, and many others deregulated, liberalized trade, and tolerated private capital and entrepreneurship more than before.

In other words: large chunks of the world moved toward the messy, unequal, market‑driven capitalism that critics dismiss as “neoliberal” or “trickle‑down.”

If you’re honest, you can’t separate that explosion in global prosperity from the spread of market incentives, private capital, and global trade — exactly the mechanism supply‑side people talk about.

C) Hong Kong: a near‑laboratory case

Hong Kong is not paradise, but it is one of the cleanest examples of: small state + low, simple taxes + extreme ease of doing business.

Historically:

For 25 years straight, Hong Kong topped the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, scoring around 90/100 — the only economy above 90. (HongKong.gov)

Government expenditure was relatively low; even recent projections have it around 20–24% of GDP, with a plan to bring it back down after COVID‑era deficits. (Budget.gov.hk)

Before recent political changes and the pandemic, Hong Kong ran years of budget surpluses and built up fiscal reserves roughly 30% of GDP in the late 2000s. (fstb.gov.hk)

The result?

A rock with basically no natural resources became one of the richest territories on Earth in a few decades.

GDP per capita exploded; living standards rose massively for ordinary people. (hkeconomy.gov.hk)

Yes, inequality is high. Housing is expensive. There are downsides. But if the claim is “a low‑tax, small‑state, ultra‑market system cannot deliver broad prosperity” — Hong Kong remains an awkward data point for that narrative.

D) Early U.S.: tiny fiscal state, huge growth

From 1790 up through the early 1900s:

U.S. federal spending was typically well under 3% of GDP outside of wars.

There was no large permanent income‑tax‑funded welfare state. That only really emerges in the 20th century, especially post‑New Deal.

During that era — with massive injustices, yes, but also massive freedom to start businesses and move — the U.S.:

Turned from an agrarian ex‑colony into the world’s top industrial and technological power by the early 20th century. (AMRO Asia)

Again, not a clean controlled experiment, but the pattern is consistent:

When governments are small and markets are free, wealth creation and innovation explode.

When governments grow and redistribute heavily, you may get more smoothing and “security,” but at the cost of dynamism.

7. “But the rich just hoard it!”

This is the most emotionally satisfying critique — and one of the weakest analytically.

A) Saving is how you get capital

When rich people don’t blow extra income on consumption, what happens?

They hold equities, bonds, private business stakes, real assets.

Those are claims on real capital: factories, software, machinery, offices, R&D labs.

At the macro level, saving and investment are two sides of the same coin.

A dollar that is not consumed becomes a dollar that finances investment somewhere:

A firm issues equity or debt.

A government (good or bad) borrows.

A bank makes a loan.

In a relatively sound, competitive system, a significant chunk of that goes into productive capital — the stuff that makes workers more productive and goods cheaper.

B) “Hoarding” is often just owning productive assets

Take Elon Musk as an easy example since he’s the “evil billionaire” that the woke lunatics love to criticize.

His net worth is overwhelmingly:

Shares of Tesla

Shares of SpaceX & Starlink

Stakes in other tech ventures (xAI, Boring Company, Neuralink, etc.)

Those are not giant piles of cash.

They are:

Factories full of workers and robots

Rocket production and launch facilities

Massive R&D teams

Satellite constellations

Networks of suppliers

Critics say “he’s worth $X billion” like that’s sitting in a vault. And even if it were… so what? Did he not earn it?

In reality, those numbers are market valuations of productive capital structures that millions of people voluntarily buy from and work for.

If you slash his after‑tax upside, you don’t magically send money “to the people.” You:

Reduce his incentive and ability to launch the next insanely risky capital‑intensive project

Reduce the probability that other would‑be innovators say “I’m going to go all‑in like that guy”

Push more talent into safe, political, or bureaucratic careers (EU)

That’s the trade‑off.

C) The low consumption of the rich is a feature, not a bug

From a “trickle‑down” perspective, the fact that the rich don’t spend every extra dollar at Starbucks is an asset.

It means incremental income at the top turns into capital formation rather than consumption.

That’s the pathway through which future productivity and living standards rise.

If you tax that away and run it through a giant state:

Some will go to useful public goods.

A lot will go to transfers and politically allocated projects with low or negative ROI.

That’s not a moral argument yet — just a description of how the cash moves.

8. Confounds: what the “trickle‑down is dead” literature actually measures

Although the critics of “trickle-down economics” aren’t necessarily stupid people, they are being intentionally misleading when they say it “doesn’t work” or is ineffective… Ineffective for what? Redistributing wealth and preventing the government from spending more? Yeah.

They’ve also chosen research designs that, by construction, are testing things differently than what I care about… and differently than what most people should care about. Would you rather: (A) cure cancer quickly or (B) decrease wealth inequality and prolong cancer cures? That’s the gist of the dichotomy here.

A) They study marginal tax tweaks, not systemic change

Hope & Limberg and similar studies look at major tax cuts for the rich within existing rich‑world democracies between 1965–2015.

During that ENTIRE era:

Governments are already big.

Welfare states are already entrenching.

Regulation is widespread and growing.

Demographics and technology are shifting.

The world economy is buffeted by oil shocks, crises, bubbles, etc.

Then we tweak top rates up or down and look for a big aggregate growth response.

From my perspective, that’s like:

“We slightly adjusted the air intake on an already heavily throttled engine, and it didn’t suddenly double in horsepower, therefore engines don’t need air.”

It tells you that, in very large welfare states, marginal cuts in top income/capital tax rates by themselves may not massively change short‑run GDP growth — especially if:

Spending stays high

Regulation stays heavy

The system remains riddled with cronyism and targeted favors

And the time horizon is short (5–10 years)

That’s not informative about Hong Kong‑style or early‑U.S.‑style environments where the whole structure (tiny state, light regulation, flat/simple taxes) is different.

B) They use short‑run averages

The typical economist’s dataset looks at:

5 or 10‑year windows after a reform

Averages across many countries

But the payoff to innovation and capital accumulation is long‑term and lumpy:

A tax/regulation environment that encourages, say, semiconductors, the internet, or biotech today might show up as a measured GDP bump only a decade later.

The payoff comes from specific sectors and big wins, not a nice, smooth, immediate uptick.

Meanwhile, regulation, demographics, and external shocks can all drown out the signal.

So when a paper says “we do not find robust evidence that top tax cuts significantly raised growth on average within 5 years,” what I actually hear is:

“Given noisy data, heterogeneous reforms, and short horizons, we can’t statistically isolate the growth payoff of marginal tax tweaks inside big states.”

That’s not the same as “the incentive logic doesn’t work.”

C) They bake in an equality norm

If your implicit rubric is:

“A policy ‘works’ if inequality falls or at least doesn’t rise much,”

… then any policy whose natural effect is to:

Increase after‑tax inequality,

While raising growth only modestly but not dramatically,

… will be branded a failure.

But that’s a value judgment, not a technical result.

If my goal is zero forced equality, acceleration of human development status and maximal innovation, I expect inequality to rise under a system that aggressively rewards high contribution and risk‑taking.

That’s not failure; that’s the price of having a steep, merit‑driven payoff structure.

So when a think tank summary says “tax cuts for the wealthy only benefit the rich,” what that often means is:

“They clearly boosted top incomes and didn’t create a huge, equalizing windfall for everyone else in the short run.” (LSE)

This is all expected stuff… the wealthy benefit more because they earn more. Not difficult to comprehend. The question is why this is automatically assumed to be a bad thing. (Most just see “rich get richer” and assume it’s something evil because they are envious.)

The problem with this view is that innovation and the baseline living standard will increase significantly faster if you embrace inequality. If you force equality or set boundaries (assuming free market, low corruption, low regulation system)… you just prolong shittier living conditions for everyone (including the poor).

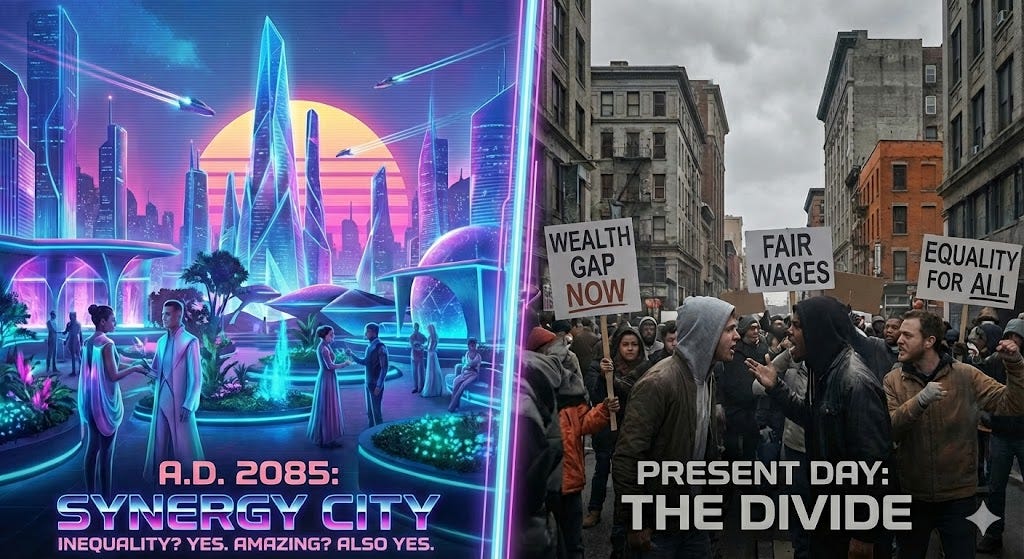

9. The philosophical split: envy & relative wealth vs. inequality & absolute living conditions

Underneath all the econometrics, there’s a philosophical split.

The current system aims to reduce relative wealth inequality to attenuate envy… the costs are slower innovation rates and less objective fairness.

An ideal system (in my opinion) aims to raise absolute living standards as rapidly as possible for everyone via innovation, even if inequality stays high or rises. The cost is living with temporarily higher envy among those not blessed with genetic talent (until they have augmentation options).

My view

Life is inherently unequal… in talent, drive, luck, risk tolerance.

A fair system doesn’t mean equal outcomes; it means voluntary exchange under equal rules.

If you create huge value in a way people willingly pay for, you should be able to keep most of it.

If you inherit wealth, your family has a right to pass it on. That may be aesthetically annoying to some, but the alternative (the state seizing it) is worse for everyone in the long-term.

Absolute living conditions for everyone, including the poorest, improve faster when you embrace inequality (lower taxes, lower regulations, capitalism).

Critics of trickle-down economics

High inequality is intrinsically bad, even if the poor are far better off in absolute terms than before.

The state has both the right and the duty to heavily tax away large fortunes to fund transfers and social programs.

“Fairness” is closer to “nobody should be too rich relative to others.”

We are willing to sacrifice a faster rate of innovation and absolute living standards to ensure short-term comfort (equality).

Once you see that value split, the policy disagreement makes sense:

If you think envy and relative financial status matter more than improving absolute living standards and innovation, you will think trickle‑down “doesn’t work” by definition.

If you think absolute living standards and innovation matter more than quashing envy, you will see a small, low‑tax, market‑driven system as exactly what you want.

I’m explicitly in the second camp.

10. The honest caveats

None of this means “government bad, markets perfect.”

I am in favor of logical, strategic, high ROI government investments (e.g. military, police, prisons, specific health interventions, etc.). But the free market should constantly be putting pressure on the government to improve too!

There are legitimate caveats:

Externalities: Pollution, pandemics, some network effects genuinely require coordinated action.

Basic safety net: Even if you hate redistribution at the margin, a minimal backstop against starvation or complete destitution may be morally justified and economically stabilizing.

Cronyism and monopoly: Left unchecked, big firms can use state power to entrench themselves and block competition — that’s anti‑market, even if it happens under the banner of “pro‑business.”

The point isn’t “zero state.”

The more the state does beyond core public goods and a lean safety net, the more it distorts incentives and turns into a mechanism for groups to live off others via politics rather than creating value.

On my fairness and prosperity metrics, that’s where things go off the rails.

11. So, does “trickle‑down economics” work?

If by “work” you mean:

Keep reward tightly linked to value creation

Incentivize maximum innovation and capital formation

Drive long‑run improvements in living standards

… then the combination of:

First‑principles incentive logic,

Cross‑country evidence on economic freedom and growth

Historical cases like Hong Kong and early U.S.

And the global collapse in extreme poverty under market‑oriented reforms

… all point in the same direction: YES.

A low‑tax, low‑regulation, high‑freedom system is the closest thing we have to a guaranteed engine of growth and innovation — and most critiques are really just complaints that it doesn’t also produce equality or a giant redistributive state.

When people tell me “trickle‑down economics doesn’t work,” what I actually hear is:

“I don’t like inequality, and I’m grading the system on that, not on whether it maximizes innovation, respects voluntary exchange, or lifts living standards over decades.”

We can argue values honestly. But let’s not pretend the system that: reduced global extreme poverty from ~38% to single digits in a generation; turns resource‑poor rocks into financial hubs; and historically turned a tiny federal government into the backdrop for the fastest rise in national wealth ever recorded… has “failed” just because it didn’t also satisfy a philosophical craving for equal outcomes.