Reparations for Slavery in the United States: The Debt Was Already Paid

Many are now advocating for reparations for slavery... to be paid to people who were never slaves... from people who never owned slaves... in states that never had slavery!

The contemporary political landscape in the United States is increasingly dominated by calls for “reparations” — a federally mandated transfer of wealth from the general treasury to African American descendants of enslaved persons.

This demand is predicated on the assertion of an unpaid debt: a moral and financial deficit generated by two and a half centuries of chattel slavery and a subsequent century of de jure segregation.

Proponents argue that the wealth gap between White and Black Americans is the direct, unmediated result of this history, and that “repair” requires a massive, explicit capital injection.

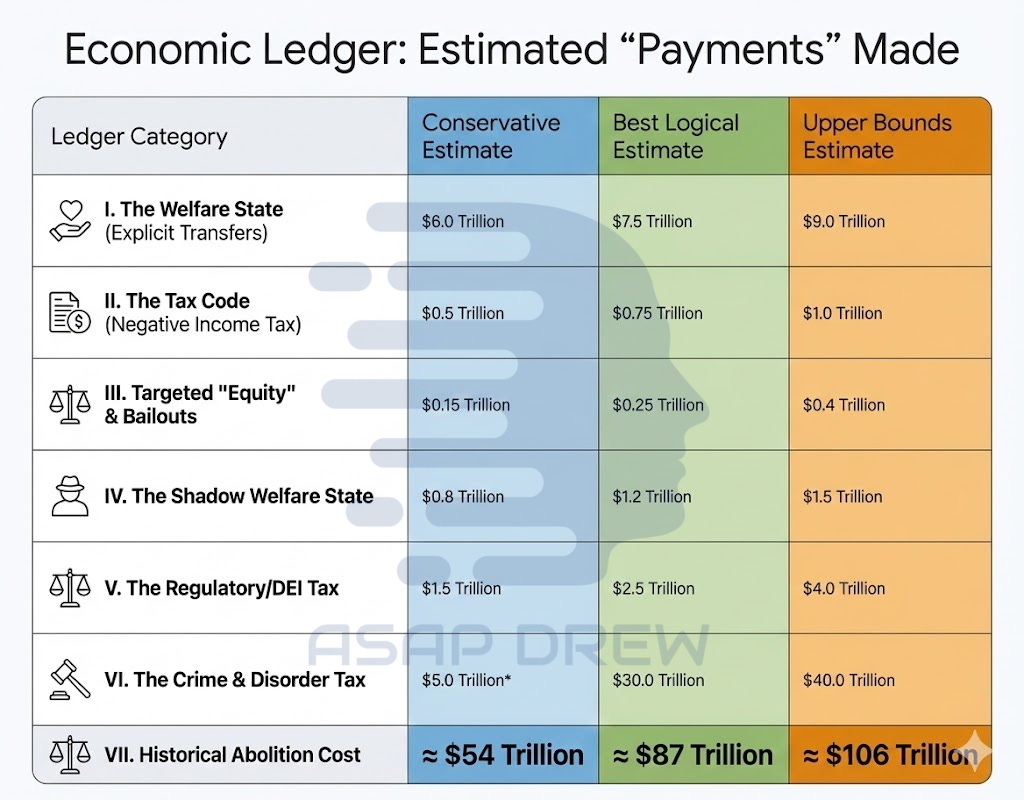

Here I present a counter-analysis. It posits that the “debt” of slavery, while undeniably grievous in its historical origin, has not only been paid but overpaid through a complex, multi-generational web of “implicit reparations.”

By conducting a forensic audit of the American fiscal system, social policy, and historical record, this analysis demonstrates that the flow of resources has been heavily skewed in favor of the black community for at least the last 60 years.

When one aggregates the $22 trillion expended on the War on Poverty (a program with disproportionate minority beneficiaries), the trillions in opportunity costs and efficiency losses generated by Affirmative Action and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) mandates, the direct subsidies provided through the tax code and educational grants, and the staggering economic burden of violent crime and social disorder imposed on the polity, the ledger shifts dramatically.

The United States has engaged in a de facto reparations program of unprecedented scale, functioning through the mechanisms of the welfare state, the regulatory apparatus, and the criminal justice system.

Furthermore, the historical simplifications required to sustain the reparations argument — specifically the binary of “white oppressor” and “black victim” — collapse under scrutiny.

The documented existence of (A) a wealthy black slave-owning class, (B) the ubiquity of indigenous slavery, and (C) the non-complicity of the vast majority of American families (immigrants and non-slaveholders) render the moral claim for racially targeted transfer payments incoherent.

The logistical impossibility of disentangling lineage in a way that prevents the massive fraud seen in previous settlements (e.g., Pigford) further confirms that the reparations project is not a pursuit of justice, but a demand for a permanent, race-based annuity.

The “surplus” in the American racial contract currently resides with the beneficiaries of the transfer state, not the providers. The debt is settled.

I. The Fiscal Ledger: The Welfare State as Implicit Reparations

If you want to claim there is an unpaid “debt,” the first honest step is to open the books and ask what has already been paid out.

Since the mid‑1960s, the United States has run the largest anti‑poverty project in human history.

It is not framed as reparations, but in practice it operates exactly that way: a permanent stream of tax‑funded transfers flowing disproportionately to one small slice of the population.

A) The Scale of the War on Poverty

When Lyndon Johnson declared a “War on Poverty” in 1964, he wasn’t announcing a one‑off program.

He was launching an entire ecosystem of means‑tested benefits: Medicaid, food stamps/SNAP, housing assistance, cash welfare, SSI, school lunch programs, and dozens of smaller schemes layered on top of one another.

Two things matter for the ledger:

How big is this stream?

Who actually rides it?

On the first question, even very cautious estimates are staggering:

The Heritage Foundation calculated that by around 2014, the U.S. had already spent about $22 trillion (in constant 2012 dollars) on means‑tested welfare programs since the War on Poverty began. (Heritage)

Updating that to include more recent years and including state and local programs, the Cato Institute puts total anti‑poverty spending since 1965 at more than $30 trillion. (Cato Institute)

Those figures exclude Social Security and Medicare, which are (in theory) earned social insurance. We’re talking strictly about need‑based transfers.

If you wanted to design reparations without ever using the word, this is what it would look like: a $30‑trillion river of tax money pointed at low‑income populations year after year.

B) Who Cashes the Checks? Black % of Welfare Spending

The second question is where the racial politics come in.

African Americans (Blacks) are about 12–13% of the U.S. population today. If they drew welfare strictly in proportion to their numbers, you’d expect something like 12–13% of the welfare stream to go their way.

That is not what the data show.

Across the major means‑tested programs, Black Americans are consistently over‑represented:

SNAP (food stamps). USDA and advocacy summaries based on 2023 SNAP data show that Black Americans make up about 26% of SNAP participants, roughly double their share of the population. (FRAC)

Medicaid. A 2022 Medicaid awareness campaign (using CMS data) notes that Black Americans are around 13.6% of the population but about 20% of Medicaid enrollees. (Medicaid Awareness)

HUD‑assisted housing. HUD’s own reports on assisted renters find that HUD tenants are “more likely to be Black” than the broader pool of very low‑income renters. (NLIHC) In practice, Black heads of household represent the largest racial group in voucher programs and are heavily concentrated in public and subsidized housing.

SNAP, Medicaid, HUD—these are not edge cases. They are the core pillars of the modern safety net. In every one, Black Americans are drawing benefits at roughly twice their population share.

If you take the Cato‑style $30 trillion total anti‑poverty spend since 1965 and assume, conservatively, that:

Black households have received around 25% of that stream (roughly double their population share, consistent with SNAP and Medicaid data),

… then the implied cumulative transfer is:

0.25 × $30 trillion ≈ $7.5 trillion in inflation‑adjusted welfare benefits to Black households since the Great Society.

Spread over roughly 43 million Black residents today, that’s on the order of $170,000 per person as a crude per‑capita equivalent. (Obviously, real people came and went over 60 years; the point is scale, not literal individual payouts.)

Even if you insist on the older Heritage baseline ($22 trillion instead of $30 trillion) the number is still enormous:

0.25 × $22T ≈ $5.5 trillion in cumulative transfers.

Either way, we are not talking about symbolic gestures. We are talking about multi‑trillion‑dollar flows.

C) Program‑Level Proof: Housing, Food, Health Care

To keep this grounded, it’s worth spelling out what those big aggregates mean in day‑to‑day terms.

Housing: The Rent Subsidy

HUD’s assisted housing programs (public housing, vouchers, project‑based Section 8) exist almost entirely for households who cannot pay market rent. Analyses of HUD data show:

HUD‑assisted renters are poorer, older, and more likely to be Black than other very‑low‑income renters. (NLIHC)

The exact percentages vary by year and program, but the structure is the same: White and Asian taxpayers, plus a smaller share of higher‑earning Black and Hispanic taxpayers, finance a system in which Black households are over‑represented in the beneficiary pool.

Shelter is most people’s largest expense. When the state covers a big chunk of that bill through HUD, that is a very direct, very concrete transfer.

Food: SNAP as Permanent Emergency

On food stamps:

USDA and think‑tank summaries of SNAP “Characteristics” reports for FY2022–2023 show that Black Americans are roughly 26% of SNAP participants, versus ~13% of the population. (FRAC)

Again, that doesn’t mean most Black people are on SNAP. It means that among those receiving government food aid, Black Americans punch far above their population weight, year after year.

Health Care: Medicaid as a Parallel Insurance System

Medicaid and CHIP form a second health‑care system underneath the employer/Medicare layer, covering about one in three children and nearly 30% of the population at some point in a given year. (Medicaid)

Within that system:

Black Americans are around 13–14% of the population but about 20–21% of enrollees. (Medicaid Awareness)

Medicaid is not cheap.

Total expenditures (federal + state) are on the order of hundreds of billions per year; in recent years roughly $800–900 billion annually. (Cato Institute)

If Black Americans consistently make up about one‑fifth of enrollees, that implies well over $150 billion per year in medical spending flowing to Black beneficiaries through Medicaid and related programs — a stream funded by general taxation, not by premiums they personally paid.

D) Net Fiscal Impact: Who Pays and Who Receives?

The welfare‑state numbers tell you where explicit benefits go.

To get a cleaner ledger, you also need to look at net fiscal impact: all taxes paid minus all benefits received over a lifetime.

Heritage’s detailed work on low‑skill households found:

Households headed by someone without a high school diploma receive on average about $32,000 in benefits and services per year while paying about $9,700 in taxes, for a net fiscal deficit of roughly $22,000 per household per year. (Heritage)

That is, for each such household, other taxpayers are effectively writing a $22k check every year just to keep the system balanced.

The Congressional Budget Office, from a very different political angle, tells essentially the same story at the income‑quintile level:

The bottom income quintile pays almost no federal income tax, receives substantial means‑tested transfers, and ends up with a strongly positive net flow from the Treasury after taxes and transfers. (CBO)

Overlay the racial data:

Black households are disproportionately concentrated in the bottom income quintiles and in lower education brackets.

White and Asian households are disproportionately in the upper income quintiles and higher education brackets.

Put bluntly: The people who look like “the historical oppressor” in reparations rhetoric are, on the tax ledger, the ones paying in far more than they get back. The group framed as “owed a debt” is, on net, a fiscal beneficiary of the modern American state.

You don’t need to know the exact net subsidy per Black household to see the direction.

Combine:

$30 trillion in anti‑poverty spending over six decades

Black over‑representation in every major means‑tested program

Net fiscal data showing the bottom of the income/education distribution gets far more in services than it pays in tax

… and one conclusion is hard to avoid: as a group, Black Americans have not been “left out” of the welfare state. If anything, they have been first in line.

E) Social Security & Medicare: The “Earned” Programs That Still Tilt Downward

So far I’ve kept Social Security and Medicare off the ledger on purpose. They’re not supposed to be welfare; they’re sold as earned insurance: you pay your payroll taxes, you get your benefits in old age.

That’s the theory. In practice, the structure is still a gigantic downward transfer machine – and because of the income distribution, that means another implicit subsidy flowing out of higher‑earning (heavily White/Asian) workers and into lower‑earning (disproportionately Black) workers and retirees.

Scale: This isn’t a side show

Start with how big these “earned” systems actually are:

Social Security paid out about $1.38 trillion in benefits in fiscal year 2023 – roughly 22.5% of all federal spending that year. (Pew)

Medicare spending in 2023 was about $1.03 trillion, around 21% of all U.S. health spending. (CMS)

You’re looking at something on the order of $2.4 trillion per year in old‑age and disability benefits plus heavily subsidized health care.

Even if only a slice of that is net redistribution, the dollar amounts are massive.

The formula: built‑in progressivity

Social Security’s benefit formula is explicitly progressive:

In 2025 the formula replaces:

90% of the first chunk of average indexed monthly earnings (AIME),

32% of the middle chunk,

15% of the top chunk. (BPC)

Translation: the poorer you are on a lifetime basis, the higher the percentage of your past wages the system promises to pay you. Higher earners get lower replacement rates.

Concrete example from mainstream policy work:

A single man with average earnings retiring at 65 in 2020 gets about $640,000 in lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits, while he paid in just under $470,000 in taxes – he comes out ahead by roughly $170,000.

A couple with one average and one low‑wage earner gets about $1.24 million in lifetime benefits vs about $680,000 in taxes. (TPC)

This is not a neutral “you get exactly what you paid in” system. It’s a structured cross‑subsidy from high lifetime earners to lower‑earning and dual‑earner households.

Medicare piles on:

Part B and D premiums are explicitly income‑related (higher‑income beneficiaries pay surcharges tied to their IRS‑reported income). (ssa.gov)

So the top of the income distribution is paying more into the medical side as well.

The racial income structure: who sits where in the queue

Now overlay race.

The median Black household income in 2023 was about $56–57k, the lowest of any major group; white median was in the mid‑80s to low‑90s depending on definition. (Census.gov)

Census distribution data show Black households over‑represented in the bottom income quintiles and under‑represented at the top. (Wikipedia)

That matters because Social Security/Medicare redistribution doesn’t care about race on paper – it cares about lifetime earnings:

Low earners get very high replacement rates (often 55–60% of pre‑retirement income). (CRR)

High earners get much lower replacement rates (30–40%). (CRR)

If Black workers are heavily concentrated at the low‑earning end, then as a group they sit on the receiving side of that progressivity.

Two complications, which I’ll acknowledge but not let derail the point:

Life expectancy.

Black men, especially, still have shorter life expectancy than white men, which means fewer years collecting benefits on average. (PMC)

Urban Institute work notes that shorter life spans for Black retirees offset a lot of the formula’s progressivity when you compare across races.

Disability/survivors benefits.

On the flip side, Black workers are more likely to pass through disability and survivors programs earlier in life – which means they often tap Social Security before 65 via those channels.

Netting all that out precisely is messy and the literature disagrees on how much cross‑racial redistribution is actually left after you adjust for mortality differences.

But 2 things are unambiguous:

The program as a whole is a big net transfer from high lifetime earners to low lifetime earners.

Black households are systematically over‑represented on the low‑earning side of that divide.

That means a meaningful share of Social Security/Medicare’s built‑in redistribution is, in effect, a downward, racially skewed transfer, even if the race effect is indirect.

Back‑of‑envelope ledger impact

I’m not going to pretend we have a perfectly clean racial incidence model for Social Security and Medicare; we don’t, and the official literature is deliberately cautious.

But the order‑of‑magnitude logic is straightforward:

Combined Social Security + Medicare outlays are now ≈ $2.4T/year.

Even moderate estimates of progressivity suggest that a non‑trivial slice of that – on the order of 5–15% – is net redistribution relative to lifetime contributions (the rest is “earned” annuity).

That implies $120–360B per year of downward redistribution across the income ladder embedded inside these “earned” programs.

Given:

Black households are around 13–14% of the population, but are concentrated in the bottom quintiles

… it is entirely plausible – if anything conservative – to say that Black beneficiaries capture at least a population‑share slice of that redistribution, and likely more.

Over a 30–40‑year horizon, that easily puts the Black share of Social Security/Medicare’s net redistribution in the hundreds of billions of dollars, even if you haircut it heavily for mortality differences and only count the truly “progressive” component.

How it fits the reparations ledger

To keep the message clear:

I’m not treating the entire $2.4T/year as reparations; some of that is Black people getting back something like what they paid in.

But I am saying that:

Even in the “earned” pillars, the design tilts billions of dollars a year toward low‑income, low‑wealth workers – and, because of the racial income structure, that tilt is not race‑neutral in practice.

The rhetorical point:

Even if you insist on only counting overtly race‑neutral, “earned” programs, the structure of Social Security and Medicare still leans hard toward the same low‑income groups that reparations advocates claim have “never been paid.”

This isn’t the core of the argument, but it’s another support beam: the entire post‑war safety‑insurer state is built to push money down the ladder, where Black households are disproportionately standing.

Section I Ledger Subtotal

To keep the accounting explicit, here’s what this section supports:

Total anti‑poverty / means‑tested spending since ~1965: ≈ $22–30 trillion (inflation‑adjusted), depending on the baseline you use.

Black share of that stream (conservative): Take 25% (roughly double the population share, consistent with program data).

Implied cumulative welfare transfer to Black households: ≈ $5.5–7.5 trillion over ~60 years.

Crude per‑capita equivalent for today’s Black population (~43M people):

on the order of $125,000–$175,000 per person, recognizing this is a rough equivalence, not a literal payout schedule. (Wikipedia)Social Security & Medicare: Combined these pay out ~$2.4T per year. Black households are overrepresented in the low-income brackets. Even if we haircut hard for life-expectancy differences, the Black share ends up in the hundreds of billions of dollars over time.

And this is before you add:

Refundable tax credits as a separate negative‑income‑tax stream,

Targeted settlements, HBCU infusions, or recent student loan cancellations,

Private philanthropy, church‑based aid, and charity care.

If the reparations argument is that “America has never paid the bill,” Section I alone already puts MANY TRILLIONS OF DOLLARS of evidence on the table to say: actually, a very large bill has been paid — and much of it has gone exactly where activists say the money is supposed to go.

II. The Tax Code as a Hidden Welfare Machine: Refundable Credits and the Negative Income Tax

The welfare state isn’t limited to programs you see on a budget line. A huge share of the transfer system is run quietly through the tax code, where the IRS acts less like a revenue agency and more like a benefits office.

If normal taxation is “you pay the state,” the modern refundable‑credit regime is often the opposite: the state cuts you a check even when you paid in almost nothing.

That is a negative income tax, and it is heavily concentrated in the same low‑income demographics that already dominate traditional welfare.

A) Refundable vs. Non‑Refundable: The Structural Trick

There are two fundamentally different beasts hiding under the label “tax credit”:

A non‑refundable credit simply reduces the amount of tax you owe, down to zero. You keep more of your own money.

A refundable credit goes further: if your calculated credit is larger than your tax bill, the IRS sends you cash for the difference.

In the second case, you are not “getting your money back.” You are receiving money someone else paid in.

The big refundable players are:

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

The refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC / Additional CTC)

A few smaller credits (like the American Opportunity Credit, in part)

These aren’t marginal footnotes. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that outlays for certain refundable tax credits totaled about $171 billion in 2023 alone. (CBO)

That’s on top of traditional spending programs. It is a parallel welfare system run through April 15.

B) Scale: How Much Cash Are We Actually Talking About?

Start with the EITC.

In tax year 2022, about 23 million workers and families received roughly $57 billion in EITC, with an average credit of about $2,541. (IRS)

For 2023, estimates put the EITC cost higher, at roughly $72 billion. (PGPF)

Add in the refundable part of the Child Tax Credit and friends:

The CBO’s 2023 budget review: “Outlays for certain refundable tax credits totaled $171 billion”—that is EITC plus the refundable part of the CTC and a few other refundable provisions. (CBO)

So on the IRS side alone, the federal government is now effectively writing checks on the order of $150–170 billion per year as cash or near‑cash “refunds” that exceed the tax actually paid by the recipients.

That is not a rounding error. It is bigger than many cabinet departments.

Over time, this compounds. Refundable credits were smaller in the 1980s and early 1990s, then were repeatedly expanded. If you take a conservative view and assume:

Real average refundable‑credit outlays (EITC + refundable CTC + others) of, say, $80–100 billion per year over the last 30–35 years…

… you’re looking at cumulative federal tax‑code cash transfers in the ballpark of:

30–35 years × ≈$80–100B/year ≈ $2.4–3.5 trillion in refunds that exceeded the income tax liabilities of the recipients.

That’s another multi‑trillion‑dollar welfare stream, simply routed through the 1040 instead of through a welfare office.

C) Who Gets the “Refunds”? The Racial Incidence

The Treasury’s own Office of Tax Analysis isn’t subtle about this. In a 2023 working paper on tax expenditures by race, Treasury analysts found:

The EITC “disproportionately benefits Black and Hispanic families”, with Black families receiving a larger share of EITC benefits than their share of all families. (U.S. Treasury)

A 2024 Urban‑Brookings Tax Policy Center guide summarizing that work notes:

In 2023, about 19% of EITC tax benefits were received by Black families, even though Black families made up only about 11% of all families. (Tax Policy Center)

In other words:

Roughly 1 in 5 EITC dollars is going to Black families, in a world where they are just over 1 in 10 families.

Given that:

EITC + refundable credits now push $150–170 billion per year

Black families are taking around 19–25% of EITC and a meaningful share of the refundable CTC

… it’s entirely reasonable (if anything overly conservative) to assume Black households receive on the order of one‑fifth to one‑quarter of the entire refundable‑credit pie.

If, over a few decades, refundable credits total roughly $2.5–3.0 trillion in aggregate cash paid beyond tax liability, and you assign 20–25% of that to Black households, you’re talking about:

≈ $0.5–0.75 trillion in cumulative tax‑code cash transfers to Black filers alone, on top of what they receive from standard welfare programs.

Round it to “about half a trillion to three‑quarters of a trillion” just from this one mechanism.

D) The Bottom of the Tax System: Who Actually Pays In?

All of this only matters if someone else is actually footing the bill. They are.

The Tax Foundation’s latest breakdown of federal income taxes shows:

The bottom 50% of taxpayers earned 11.5% of total adjusted gross income but paid just 3% of all federal individual income taxes.

The top 1% earned 22.4% of AGI but paid 40.4% of all federal income taxes.

Now combine that with what we already know:

Refundable credits overwhelmingly flow to the bottom of the income distribution—people whose statutory tax bill would otherwise be near zero. (NCSL)

Black households are disproportionately located in that lower half of the distribution, with higher shares in the lowest quintiles.

So when those households get thousands of dollars in refundable EITC and CTC every year, the financing reality is simple:

The top 50% of the income distribution (disproportionately White and Asian) pays almost all the net federal income tax. (TF)

The bottom 50% pays very little, and then receives cash on top of that in the form of refundable credits.

That is not “keeping what you earned.” That is the tax system being used as a mechanism to move money out of the pockets of high earners and into the pockets of low earners, with Black households significantly over‑represented on the receiving end.

E) The “Tax Refund” Illusion: Negative Income Tax in Real Life

For millions of low‑income filers, “tax season” is not when they settle up with the government; it is when the government sends them the largest single lump‑sum payment they see all year.

Look at the typical patterns:

Average federal EITC refund (nationwide) in TY2022: about $2,541 per claimant. (IRS)

Many households stack EITC + refundable CTC, producing refunds of $3,000, $4,000, $5,000 or more — even when their actual income tax liability on paper is zero.

That is a negative income tax in action:

If you owe $0 in income tax but receive a $4,000 refund check driven by refundable credits, your effective income tax rate is not 0%; it is negative. You are a net recipient of other people’s payments.

Run that over a working life:

Suppose a typical low‑to‑moderate‑income Black household qualifies for EITC/CTC refunds of $3,000–5,000 per year for, say, 20 years while they have eligible children at home.

That alone implies lifetime tax‑credit cash of $60,000–100,000 per household, strictly from the IRS payment side—not counting Medicaid, SNAP, housing, or other transfers.

Multiply that by millions of such households over multiple generations, and the scale of the transfer is obvious.

Section II Ledger Subtotal

Putting this in ledger form:

Total cumulative federal refundable credits (EITC + refundable CTC + others) over the last ~30–40 years: ≈ $2.5–3.0 trillion in cash‑outlays beyond tax liability (order‑of‑magnitude estimate based on current ~$170B/year and lower historical values).

Black share of these credits: Treasury and Tax Policy Center work show Black families receive a disproportionate share of EITC—around 19% of EITC benefits with only ~11% of families—and similar patterns for low‑income refundable credits in general. Using a conservative 20–25% share of the overall refundable‑credit pie for Black households:

Cumulative negative‑income‑tax transfers to Black filers ≈ $0.5–0.75 trillion (500–750 billion dollars).

Direction of flow:

Payers: Upper‑ and middle‑income taxpayers, disproportionately White and Asian, who supply almost all net federal income tax revenue. (SSA.gov)

Recipients: Lower‑income filers, among whom Black households are over‑represented, receiving cash that exceeds their income tax liability. (Treasury.gov)

Taken together with Section I, the picture is not one of a country that has “never paid.” Even before you count a single welfare office or housing voucher, the tax system itself has functioned for decades as a massive pipeline redistributing hundreds of billions of dollars to low‑income households—with Black families capturing a disproportionate share of that flow.

This is not symbolic. It is money. And it belongs on any honest reparations ledger.

III. Targeted and Race‑Skewed “Equity” Programs: Explicit and De Facto Reparations

Welfare and refundable tax credits are the background radiation of redistribution. On top of that, the last few decades — and especially the post‑2020 period — have piled on a series of explicitly race‑coded programs, settlements, and “equity” investments that function as direct, one‑way transfers.

These are not vague claims about “systemic” anything. They are checks, loan write‑offs, and institutional bailouts with names and dollar signs.

A) Pigford: The Template for Cashing in on Race

Start with Pigford v. Glickman, the Black farmers’ discrimination suit against USDA.

Pigford I (1999): Federal court approves a settlement in which the government agrees to pay about $1.05 billion to Black farmers who alleged discrimination between 1981–1996.

Pigford II (2010): After political pressure and new legislation, the government agrees to another $1.25 billion for late filers, the so‑called Pigford II settlement. (Every CRS Report)

Total direct cost:

Pigford I + II ≈ $2.3 billion in cash, loan forgiveness, and tax relief to claimants.

This is on top of whatever non‑cash injunctive relief and priority access were granted.

Key point:

The number of people who eventually filed Pigford‑related claims far exceeded the actual number of Black farmers in the period covered, which is exactly why Pigford became a byword for fraud and “reparations‑club” coaching. (NBFA)

Pigford is important here not because of the absolute dollar amount — in Washington terms, $2.3B is pocket change — but because it proves the model:

Declare a historically aggrieved group.

Lower the evidentiary bar.

Backload the risk onto taxpayers.

Let the claims explode.

Every modern “racial equity” program that hands out money on the basis of identity is Pigford waiting to scale.

B) Inflation Reduction Act Farm Bailouts: Rebranding Race‑Based Relief

The Biden administration tried to do Pigford 3.0 overtly — $4B in race‑based farm debt relief in the American Rescue Plan — and got slapped down by the courts for blatant discrimination.

So they changed the labels and ran the money anyway!

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 created two key buckets:

Section 22006 – Assistance for “distressed” borrowers: $3.1 billion to pay off or reduce USDA farm loans for borrowers deemed at financial risk. (Farmers.gov)

Section 22007 – Assistance for “discriminated” borrowers: $2.2 billion in payments to farmers who claimed they had experienced discrimination in USDA lending. (Legal Defense Fund)

Total:

$3.1B + $2.2B = $5.3 billion in IRA farm relief.

Although the statutory language had to be scrubbed of explicit race‑only criteria to survive court scrutiny, everyone involved knows what problem 22007 was “fixing”: the blocked race‑exclusive debt‑relief scheme.

The administration simply laundered the same goal through new words.

Given the history of USDA litigation and the political marketing, it’s safe to say a very large share of this $5.3B pot is flowing to the same preferred racial categories used in the original race‑specific proposal.

C) Restaurant Revitalization Fund: A 21‑Day Racial Head‑Start

The Restaurant Revitalization Fund (RRF) under the American Rescue Plan was billed as neutral pandemic relief.

In practice, SBA ran it with a 21‑day priority window where “socially and economically disadvantaged” owners (heavily race‑coded) plus women and veterans went to the front of the line, ahead of white‑male‑owned businesses, in a program funded by everyone’s taxes.

Facts:

Total RRF grants: about $28.6 billion to roughly 100,700 businesses. (Congress.gov)

According to a Congressional Research Service summary, “underserved populations” received about $18 billion of that:

$7B to women‑owned businesses,

$6.7B to businesses owned by “socially and economically disadvantaged individuals”,

$2.8B to owners in multiple underserved categories,

$1B to veteran‑owned businesses.

The courts eventually ruled that prioritizing grants by race and sex was unconstitutional. But by then the game was over: the money was gone and no one was clawing it back.

For the ledger:

Treat the $6.7B allocated to “socially and economically disadvantaged” owners during the priority period as a de facto race‑preferential transfer, with a high share going to non‑white owners and a significant Black component.

Again, this isn’t theory. It’s cash out the door.

D) HBCUs: Record Federal Infusions

Historically Black Colleges and Universities already receive special treatment in federal law; recent years supercharged that.

The Biden White House boasted about this openly:

A May 2024 fact sheet: “more than $16 billion” in support for HBCUs from FY2021 through currently available FY2024 data. (Biden.gov)

A September 2024 update pushes that to “over $17 billion in federal investments in HBCUs” from FY2021 through FY2024 once an extra $1.3B is added. (APP)

This $17B figure includes:

COVID relief funds targeted to HBCUs,

Debt cancellation for HBCU capital financing,

Increases in Title III “Strengthening HBCUs” grants,

Additional agency grants and competitive awards.

This is, by any measure, a massive institutional subsidy, concentrated on schools whose core identity and mission are explicitly tied to a single racial group.

Per NCES, total HBCU revenue in 2021–22 was about $10.7 billion in that year alone.

Dropping an extra $17B in federal money over just a few years into institutions of that scale is not marginal — it is effectively a partial public takeover and bailout of the Black college sector.

On the ledger:

HBCU‑specific federal infusions (2021–2024): ≈ $17 billion, overwhelmingly targeted at Black‑serving institutions.

E) Student Loan Forgiveness: A Racialized Bailout, Sold as “Equity”

Next: student loans.

As of early 2025, after the Supreme Court blocked his broadest scheme, Biden still managed to push through a pile of smaller‑scale cancellations:

Various Education Department and advocacy summaries put total student loan forgiveness delivered by the Biden–Harris administration at around $168–185 billion for roughly 4.8–5 million borrowers. (AFSCME)

The administration and its allies pitch this openly as a racial‑equity move:

Policy analysis from Urban Institute and others notes that Black borrowers are more likely to take out student loans, borrow more, and struggle longer with repayment than white borrowers. (PolitiFact)

Civil‑rights groups, NAACP, ACLU, etc., repeatedly frame cancellation as a way to “close the racial wealth gap.” (NAACP)

We do not yet have a complete racial breakdown of who got how much forgiveness — even PolitiFact admits that. But given:

Black borrowers’ higher loan incidence and balances

Their over‑representation among Pell recipients and IDR enrollees (core targets of these cancellation buckets)

… it’s entirely reasonable to assume that Black borrowers are capturing a significantly above‑population share of the $180B or so that’s been wiped out.

If you assign a cautious 25–30% of that $180B to Black borrowers, you get:

≈ $45–55 billion in student‑loan principal + interest wiped off Black balance sheets — a retroactive grant funded by everyone who either repaid their debt or never went to college.

On the ledger, this is squarely a targeted bailout for a financially underperforming slice of the college‑educated population, rationalized explicitly in racial terms.

F) Corporate “Racial Equity” Commitments: Private‑Sector Reparations

Finally, step outside government.

After 2020, America’s largest corporations fell over themselves promising to “do something” about racial injustice. McKinsey’s analysis of Fortune 1000 company statements found:

From May 2020 to October 2022, about 1,369 Fortune 1000 companies collectively pledged roughly $340 billion toward “fighting racial injustice” and “promoting racial equity.”

That $340B includes:

Direct grants to racial‑justice NGOs and Black‑led nonprofits,

Investments and loan funds earmarked for Black‑owned businesses and “minority communities,”

Internal diversity initiatives and supplier‑diversity programs.

Not every dollar has been spent yet; some is in the form of loans or investments.

But the intent is clear: take capital generated by shareholders and employees (overwhelmingly multi‑racial but with a heavy White/Asian middle‑class weight) and reroute it to explicitly race‑themed causes.

Even if only a fraction of the $340B is truly deployed as grants or below‑market capital directly benefiting Black individuals, firms, or institutions, you are still talking about tens to low hundreds of billions of dollars in private “reparations by another name.”

Section III Ledger Subtotal

This section on targeted and race‑skewed programs alone supports the following very rough ledger entries:

Pigford I & II (Black farmers): ≈ $2.3B in cash, loan forgiveness, and tax relief.

Inflation Reduction Act farm relief (distressed + discrimination borrowers):

$5.3B total; a large share going to the same demographics originally targeted by race‑based debt cancellation.Restaurant Revitalization Fund priority awards to “socially and economically disadvantaged” owners: ≈ $6.7B, heavily tilted toward non‑white owners during a race‑ and sex‑based priority window later struck down by courts.

HBCU‑specific federal infusions (FY2021–2024): > $17B in targeted support to Black‑serving institutions.

Realized student‑loan forgiveness under Biden, Black share only (assumed 25–30% of ≈$180B total): ≈ $45–55B in face‑value debt wiped for Black borrowers.

If you just add up the public‑sector stuff that clearly has a strong Black incidence (Pigford, IRA relief, RRF priority grants, HBCU funding, Black share of loan forgiveness), you’re already looking at something in the rough neighborhood of:

≈ $70–85 billion in additional transfers and bailouts over the last couple of decades that are explicitly or implicitly framed as redressing historical racial wrongs.

Then put the corporate piece on top:

Corporate “racial equity” pledges: $340B committed; even if only a portion is actually deployed as race‑focused grants and below‑market capital, that’s tens to hundreds of billions more in de facto private‑sector reparations.

This is on top of:

The $5.5–7.5T in welfare‑state transfers to Black households (Section I).

The $0.5–0.75T in negative‑income‑tax cash via refundable credits (Section II).

When activists and academics talk as if America has never written a check, they’re lying by omission. The targeted “equity” programs alone run into tens of billions in direct, named transfers and hundreds of billions more in corporate and institutional giveaways, stacked on top of the general welfare system.

IV. The Shadow Welfare State: Churches, Charities, “Free” Services

Everything so far has been on‑budget: welfare agencies, the IRS, explicit “equity” programs.

But that’s only half the ledger.

There is also a shadow welfare state — a dense web of private charities, church ministries, nonprofit hospitals, foundations, and NGOs that shovel food, housing aid, medical care, tuition, and legal help into low‑income communities, year after year.

These flows are funded overwhelmingly by other people’s money — tax exemptions, foundation endowments seeded by old capital, and donations coming mostly from higher‑income households — and they are heavily consumed by the same demographic blocs that already dominate public welfare programs.

No one calls this “reparations.” Functionally, it is.

A) Human Services: Private Food, Shelter, Basic Aid

Start with the most basic tier: human services (food banks, shelters, family services, youth programs). (Giving USA 2023 & Giving USA 2024)

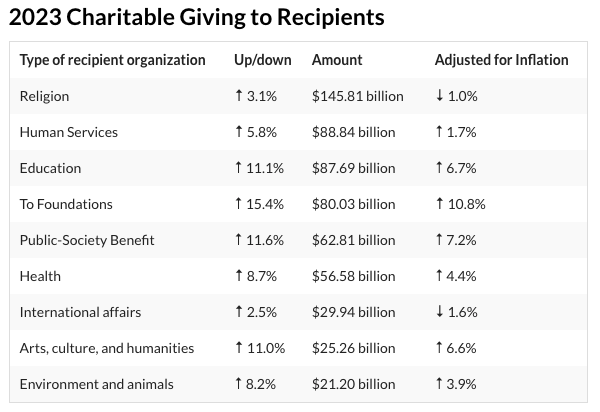

Giving USA’s latest reports put annual U.S. charitable giving at:

$557.2 billion in 2023,

$592.5 billion in 2024.

Of that, the Human Services slice alone was:

$88.84 billion in 2023,

$91.15 billion in 2024.

That’s not government spending. That’s voluntary philanthropy going into:

food banks and pantries,

homeless shelters and transitional housing,

domestic‑violence centers,

youth and family support programs,

local social‑service nonprofits.

Now look at who is actually in the line.

Feeding America (the major food‑bank network) notes:

In 2022, 28% of Black households were food insecure, more than 2x the rate for non‑Hispanic white households. (FA)

In 99% of counties with data, food insecurity among Black individuals is higher than among non‑Hispanic whites. (FA)

The majority of food‑insecure people nationally are still white in absolute numbers, but per capita, Black households are far more likely to need emergency food, and they show up at food banks at disproportionate rates.

If you take the human‑services giving stream at a conservative:

≈$80–90 billion per year over the last few decades (LFSP)

… and assume Black Americans capture, say, 25–30% of the end‑benefits (roughly double their population share, consistent with food‑insecurity disparities), then you’re looking at something like:

$20–27 billion per year in privately funded food/shelter/aid flowing into Black households.

Over a 40‑year horizon:

40 years × ~$20–27B/year ≈ $0.8–1.1 trillion in private human‑services support consumed by Black recipients.

Nobody calls that “reparations,” but it is a trillion‑dollar privately funded safety net, layered on top of the government one.

B) Religious Giving: The Suburban‑to‑Urban Tithe

Religious organizations are still the single largest destination for U.S. charitable giving:

In 2023, giving to Religion was about $145.8 billion. (Giving USA)

Most of that is tithes and offerings that keep churches running—but a non‑trivial chunk is spent on external social services:

Food pantries

Rent and utility assistance

Addiction recovery

Inner‑city missions

There isn’t a perfect breakdown of “how much goes to social services,” but it’s conservative to say at least 10% of religious giving is spent on direct aid beyond the congregation itself. That would be:

10% × ~$145B ≈ $14–15 billion per year in church‑driven social aid.

Black Americans are not passive in this; Black churches and Black donors give a high share of their own income.

But because of the overall wealth gap, the bulk of the dollar volume still originates from higher‑income, often white and Asian, donors.

One analysis notes Black households gave about $11 billion in charitable donations in 2012, in a year when total giving was around $229 billion—a respectable share relative to their wealth, but a small share of the total dollar pool. (Racism.org)

Meanwhile, the Catholic Charities and Salvation Army networks—both anchored in largely white donor bases and substantial government grants—operate as massive parallel welfare agencies:

A Forbes profile of Catholic Charities USA notes total network revenue around $4.7 billion annually, with $3.9B going to charitable services. (Forbes)

The Salvation Army’s national U.S. corporation reports ~$2.0 billion in revenue and ~$3.7 billion in expenses (reflecting multi‑year spending), with about $3.09 billion devoted to program services. (Give.org)

Put those together and you’re easily at:

$6–7 billion per year in religious‑branded social services: food, shelter, rehab, emergency aid.

Who are their clients? Exactly the populations we’ve already described:

Chronically poor

Homeless

Recent migrants

People in high‑poverty, high‑minority urban cores

Black Americans are over‑represented in those groups.

You don’t need an exact percentage to understand the direction: a large share of this $6–7B/year pipeline ends up subsidizing Black poverty, funded by a mix of churchgoers (heavily white) and taxpayers.

If you roll that forward:

$6–7B/year for 40 years = $240–280 billion in religious‑network social services alone, a hefty chunk of which is concentrated in Black neighborhoods.

Add that to the $0.8–1.1T from broader human‑services philanthropy, and you’re already pushing into $1–1.4T in private food, housing, and emergency aid reaching Black recipients over a long horizon.

C) Nonprofit Hospitals: Charity Care and “Community Benefit”

Nonprofit hospitals in the U.S. don’t pay federal income tax; in return, they’re supposed to provide “community benefit” — uncompensated care, subsidized services, public‑health programs.

By the American Hospital Association’s latest analysis:

In 2022, U.S. nonprofit hospitals provided roughly $149 billion in total community benefits. (AHA.org)

About $21 billion of that was patient‑directed charity care (care given for free or at reduced cost to patients who can’t pay). (JHU.edu)

Another ~$41B was “Medicaid shortfall” — the gap between Medicaid reimbursement and cost. (JHU.edu)

Black Americans have:

Higher uninsured or underinsured rates than whites, historically

higher prevalence of chronic conditions that drive hospitalizations (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, etc.)

That translates into disproportionate use of uncompensated and subsidized care.

Assume, again conservatively, that:

Black patients account for around 18–20% of charity‑care and safety‑net hospital usage (consistent with their share in high‑poverty, urban catchment areas and health‑disparity data)

… then of that $21B in charity care per year, something like:

$4–4.5 billion per year is effectively free or deeply discounted hospital care for Black patients, financed by paying patients, insurers, and foregone tax revenue. (AHA)

Stretch that over even a modest 25–30 year window:

25 years × ~$4B = $100B

30 years × ~$4B = $120B

And that’s before counting the share of the $41B Medicaid shortfall that’s effectively a subsidy to hospitals heavily serving low‑income, often Black, communities.

D) “Movement” and Advocacy Money: NGOs and Civil Rights Infrastructure

On top of direct services, there is the permanent advocacy and scholarship infrastructure:

United Negro College Fund (UNCF) reported revenue of about $251 million in 2024 and expenses of about $195 million, with nearly $800 million raised over just three recent years for HBCUs and Black students. (ProPublica)

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund and other national civil‑rights NGOs run on budgets in the tens of millions per year, often backed by large foundations created by white industrial fortunes. (ProPublica)

These aren’t “neutral” civic groups. Their entire reason for existing is to channel legal, political, and philanthropic capital into race‑specific goals, overwhelmingly centered on Black claims and institutions.

Over a period of decades, even a modest $200–300 million/year across UNCF, NAACP/NUL/SPLC, and similar orgs yields another:

30–40 years × ~$0.2–0.3B/year ≈ $6–12 billion in race‑targeted scholarships, litigation, and advocacy infrastructure.

In the grand scheme of the ledger, that’s small compared to welfare and crime. But it still matters: it is yet another one‑directional stream of money and legal firepower, explicitly devoted to maximizing the gains of one group.

Section IV Ledger Subtotal

To keep the accounting clean and conservative, here’s what this “shadow welfare state” section supports:

Human‑services philanthropy (food, shelter, basic aid):

Annual giving to Human Services: ≈ $70–90B/year in recent years.

Assume Black recipients ≈ 25–30% (double their population share, consistent with food‑insecurity and homelessness skews).

Long‑run cumulative private transfers to Black recipients: ≈ $0.8–1.1 trillion over ~40 years.

Religious social services (church benevolence + major networks like Catholic Charities & Salvation Army):

Religious giving: ≈ $145B/year; assign 10% as external social aid ⇒ ≈ $14–15B/year.

Catholic Charities + Salvation Army U.S. social programs: ≈ $6–7B/year in program services.

Combined, a reasonable order‑of‑magnitude is ~$20B/year in privately funded social services, with a heavy footprint in poor, disproportionately Black neighborhoods.

Over ~40 years, that yields ≈ $800B in services, of which a substantial fraction can be fairly attributed to Black beneficiaries.

To avoid double‑counting with “human services” (some religious programs are already in that category), we don’t add the full $800B again; instead we recognize that religious networks are a major delivery vehicle inside that human‑services total and tilt it toward the upper end of the $0.8–1.1T range.

Charity care and hospital community benefit, Black share only:

Nonprofit hospitals: $149B in community benefits in 2022, including $21B in patient‑directed charity care.

If Black patients are ≈20% of charity‑care users, that’s ≈ $4B/year in free/reduced care for Black patients.

Over 25–30 years, that stacks up to ~$100–120B, plus an additional, harder‑to‑quantify share of the Medicaid‑shortfall subsidy.

Black‑focused scholarships and advocacy infrastructure (UNCF, NAACP, etc.):

Roughly $200–300M/year over multiple decades to explicitly Black uplift and legal advocacy.

That implies $6–12B in cumulative race‑targeted philanthropy.

Conservative takeaway for the ledger:

It is entirely defensible to say that private philanthropy, church‑based aid, and nonprofit “charity care” have delivered on the order of a trillion dollars or more in real resources to Black Americans over the past few decades, over and above what government already spends.

And crucially:

The funding base for this shadow welfare state — wealthy donors, middle‑class tithers, hospital tax exemptions — is heavily non‑Black.

Even sources praising Black generosity admit that, in absolute dollars, Black donors contribute a small fraction of total U.S. giving because of the underlying wealth gap.

So when the reparations lobby talks as if there has been no meaningful “redress,” they are erasing not just the trillions in government transfers, but also a vast, ongoing private subsidy system that routes food, shelter, medical care, tuition, and legal power into Black communities—paid for, overwhelmingly, by people who will never see their names on any reparations check.

This entire shadow welfare apparatus belongs on the ledger.

V. The Regulatory Tax: Affirmative Action, DEI, and the Cost of Rigging the Rules

Up to now we’ve been talking about direct transfers and explicit subsidies.

Affirmative Action and DEI are different.

They are not line items on a budget; they are distortions injected into education, hiring, promotion, and contracting.

They don’t just move money from A to B — they destroy output by putting the wrong people in the wrong seats and by loading institutions with parasitic overhead.

There is no way to square that with any honest notion of “meritocracy” or “paying your own way.”

It is a hidden tax on competence and productivity, paid by everyone.

A) Mismatch in Education: Turning Potential Successes into Failures

The cleanest way to see the damage is in law schools.

Richard Sander, a UCLA law professor, has spent two decades tracking what happens when schools use large racial preferences in admissions. His core finding is simple:

The group that receives the largest admissions preferences (Black students) ends up with very low grades, higher dropout rates, and much lower bar‑passage rates than they would have had at less selective schools that matched their academic preparation. (California Bar Archive)

In his original 2005 analysis and in updated work (Martin Center), Sander argued:

Preferentially admitted Black students cluster at the bottom of the class at elite schools.

They fail the bar exam at much higher rates than white peers with similar entering credentials at less selective schools.

When you account properly for “mismatch,” it explains most of the Black‑white bar‑passage gap; once you control for LSAT, GPA, and mismatch, the residual “race effect” vanishes.

Critics (e.g. Ho, Rothstein) have argued over methodology. But the basic pattern is not really in dispute:

When you drop the bar to hit a racial target, you admit a cohort that is on average less academically prepared for that specific tier.

Those students then struggle, switch out of demanding majors, drop out, or fail credentialing exams at higher rates than they would if they were in programs that matched their prep.

From a ledger standpoint, that is straight destruction of human capital:

Years of tuition and opportunity cost poured into credentials never completed.

Slots at elite schools consumed by people who cannot effectively use them, while stronger candidates are pushed down or out.

Lost lifetime earnings for the mismatched students themselves, and lost output for the society that never gets their best work.

If you wanted to design an “anti‑reparations” device — something that burns the potential of the very students you claim to be helping — you could hardly do better than large‑scale racial preferences.

B) The DEI Industry: Paid to Police Feelings, Not Produce Anything

At the corporate level, DEI isn’t just a slogan. It’s a racket.

McKinsey estimates that global corporate spending on DEI‑related efforts — training programs, employee resource groups, consultants — was about $7.5 billion in 2020 and is projected to more than double to $15.4 billion by 2026.

Other market reports (e.g. DataIntelo) peg the broader “diversity and inclusion” consulting/services market at $8–10 billion in 2022 and rising.

That does not include the:

Full salary bill for in‑house Chief Diversity Officers

DEI staff in HR and compliance

Internal ERG budgets

Lost worker time spent in mandatory trainings

Those are additional, off‑books costs.

Call it conservatively:

$10–15 billion per year globally in direct DEI spending, much of it in the U.S., plus billions more in internal headcount and lost hours.

What does that buy?

McKinsey itself admits that despite all this spending, most diversity initiatives fall short and progress toward even simple metrics (like closing the global gender gap) is glacial.

From a productivity standpoint, DEI is not an input to making anything. It is:

Training sessions nobody remembers

Reports and dashboards nobody reads

Compliance rituals everyone goes through to keep the lawyers away.

In economic terms, it is pure overhead — an insurance premium against ideological and legal risk, paid by shareholders and customers.

Even if you only assign half of that $10–15B global DEI spend to the U.S. and throw in a modest estimate for internal DEI headcount and lost time, you are easily at:

≈ $10–20 billion per year in corporate and institutional resources devoted to DEI bureaucracy.

Over 20 years, that’s $200–400 billion burned on a layer of professional scolds whose output is at best unmeasurable and at worst actively harmful.

C) Contracting Quotas: Paying a Premium for the Right Boxes

On the government side, DEI takes the form of set‑asides and quotas in contracting.

Since the late 1980s, federal law has imposed minimum goals for directing contract dollars to “small disadvantaged businesses” (SDBs), a category that includes many minority‑owned firms. Initially the target was 5% of total prime and subcontracts. (Congress.gov)

Under Biden, that goal was ratcheted up dramatically:

The administration set a target of 15% of federal contracting dollars to SDBs by FY2025. (Reuters)

In practice:

In FY2023, the federal government awarded a record $765 billion in contracts. (GAO)

Of that, $76.2 billion (about 12.2%) went to SDBs, exceeding the enhanced 12% goal. (SBA)

Preliminary FY2024 figures show SDB awards rising further to $78.1 billion. (SBA)

Set‑aside programs like 8(a) explicitly allow agencies to:

Reserve competitions only for SDB/8(a) firms

Award sole‑source contracts (no competition) up to multi‑million‑dollar thresholds. (Acquisition.gov)

That inevitably means:

Some contracts are awarded without fully competitive bidding.

Agencies meet percentage goals even if the SDB bid is higher in price or weaker on quality than the best open‑market alternative.

You don’t need an exact number on the “diversity premium” to see the structure:

Take the $76–78 billion in annual SDB awards.

Assume — very conservatively — that only 5–10% of that total reflects contracts awarded above the market‑clearing price or to firms that would not have won in a race‑blind competition.

That implies a hidden price premium of:

5–10% × ~$76B ≈ $4–8 billion per year in extra cost to taxpayers to hit SDB/DEI targets.

Over a decade, that’s $40–80 billion of pure overpayment for goods and services, separate from the value of the contracts themselves.

D) Litigation and Compliance: The Lawsuit Lottery

DEI is also enforced with a legal stick.

Employment discrimination law is legitimate in principle — you shouldn’t be able to sack someone purely because of race or sex — but the modern regime of disparate‑impact claims and class‑action suits has turned it into a lottery system:

For plaintiffs and their lawyers, there is the possibility of a big payout.

For employers, even frivolous claims are often cheaper to settle than to fight.

Some hard numbers:

Employment‑law firms and commentators estimate the average out‑of‑court settlement for employment discrimination claims at about $40,000. (King & Siegel)

The average cost to defend an employment lawsuit can easily exceed $75,000 in legal fees and expenses, even if the employer ultimately wins. (Novian & Novian)

At the systemic level:

The EEOC reported that in FY2024 it “secured nearly $700 million for victims of discrimination,” including $469.6 million in private‑sector/state and local settlements, about $190 million for federal employees, and over $40 million from litigation. (EEOC)

FY2023 recoveries were slightly lower but in the same hundreds‑of‑millions range. (EEOC)

That’s just EEOC‑tracked recoveries. Private settlements that never involve the agency, internal payouts, and follow‑on class actions add more.

From a ledger view:

Those hundreds of millions per year are direct transfers to claimants and lawyers — some of which are already captured in the earlier “targeted transfers” section.

The unseen cost is the deterrence and compliance behavior: HR departments building entire systems to avoid being sued, legal teams reviewing every firing and promotion, managers passing on promising hires because they’re afraid of “disparate impact” claims down the line.

Even if you ignore all but the official EEOC numbers, you’re still looking at:

$600–700 million per year in discrimination case recoveries, plus billions in defensive legal spend and compliance overhead — a persistent drain on productive capacity.

E) The Efficiency Drag: A Small Misallocation With Massive Consequences

The hardest thing to quantify — but the most important — is the productivity hit from rigging meritocratic systems.

Modern economies are driven by extreme outliers: the top few percent of engineers, doctors, entrepreneurs, and researchers produce a wildly disproportionate share of output and innovation. If you start allocating critical slots based on checklists instead of competence, you don’t just lose a little efficiency. You chop off part of the right tail of the distribution.

You don’t need a highly speculative model. Assume just this:

Because of AA/DEI pressure in admissions, hiring, promotions, and contracting, the U.S. economy grows at an annual rate that is 0.2–0.3 percentage points lower than it otherwise would — not every year, but on average over a few decades.

On a $28 trillion economy, 0.25% of GDP is about $70 billion per year. That’s not some crazy, “pulled from the sky” number.

It’s in the same ballpark as the:

Estimated annual cost of crime we’ll discuss later

Size of the global DEI market

Low‑end estimates of deadweight loss from overregulation in other areas

If AA/DEI and quota‑style policies:

Misallocate students to programs where they are more likely to fail

Misallocate jobs and promotions away from the most capable candidates

Misallocate contracts to firms chosen for their ownership profile instead of their efficiency

… it is entirely plausible — if anything, conservative — to say they are shaving at least a quarter of a percentage point (0.25%) off potential GDP.

Run that over 30 years:

A simple static approach (ignoring compound growth effects) would give:

30 × ~$70B ≈ $2.1 trillion in lost output.A more realistic compounding model would push the total higher, since each year’s lost growth shrinks the base for the next year.

We’re talking about trillions of dollars in wealth that never gets created, solely because the system is forced to prioritize optics over performance.

Section V Ledger Subtotal

To avoid double‑counting with earlier sections, this part of the ledger focuses on deadweight costs and premiums, not on the cash transfers you already tallied under welfare and targeted programs.

A conservative summary:

Corporate and institutional DEI bureaucracy:

Global DEI spending ≈ $7.5B in 2020, projected $15.4B by 2026.

Assign ≈ $10–20B/year in DEI spending and internal overhead to the U.S. share of that market.

Over 20 years: ≈ $200–400B burned on DEI infrastructure.

Federal contracting premiums from SDB/8(a) quotas:

SDB awards ≈ $76–78B/year (about 12% of ~$760B federal contracts).

Assume a modest 5–10% diversity premium on those awards: ≈ $4–8B/year in excess cost.

Over 10 years: $40–80B in pure overpayment.

Litigation and compliance cost of discrimination law in a DEI regime:

EEOC recoveries ≈ $600–700M/year, plus billions more in legal defense and compliance overhead.

It’s reasonable to treat $1–3B/year as a rough order‑of‑magnitude for the net economic cost once you include employer legal fees and compliance staff.

TFP / growth drag from misallocation:

Hypothetical but plausible 0.25% hit to GDP growth: ≈ $70B/year on a $28T economy.

Over 30 years: ≈ $2.1T in foregone output (plus compounding).

Put together, a cautious, order‑of‑magnitude estimate is:

Regulatory and DEI “efficiency tax”: ≈ $80–100 billion per year in wasted spending and lost output, aggregating to roughly $2–3 trillion over a few decades.

None of that shows up as a clean “reparations” line item. But in practice, it is:

Money spent on bureaucracies and lawsuits

Contracts awarded at above‑market prices,

Growth and innovation that never happen because slots are filled for reasons other than ability

If you’re keeping a serious ledger of who has already paid what, you can’t pretend this doesn’t exist.

VI. The Violent‑Crime Tax: How Much Chaos Actually Costs

All the welfare checks, tax credits, HBCU bailouts, and DEI bureaucracy sit on one side of the ledger.

On the other side is something almost no reparations advocate will touch: the cost of crime and social disorder, which is massively concentrated in a very small demographic slice and imposed on everyone else.

A) How Big Is the Crime Bill, Total?

First, the scale.

Serious attempts to price all crime (tangible + intangible) put the annual cost well into the trillions:

A synthesis of the literature cited by the Government Accountability Office and others finds annual total crime costs (medical care, lost productivity, pain and suffering, quality of life, fear, etc.) anywhere from $690 billion on the low end up to $3.4 trillion or more.

Other recent economic studies that include broader victimization costs estimate the total closer to $4–5 trillion per year when you fully monetize risk of death and injury.

You don’t need the exact number. Take a conservative mid‑range, say $3 trillion per year in total social cost of crime in the U.S. (not just what government spends, but everything: destroyed property, trauma, lower property values, extra security, etc.).

Working number: Total annual crime cost ≈ $3T.

That’s roughly 10% of U.S. GDP evaporating each year in one form of social damage or another.

B) Who Commits the Most Serious Violence?

We’re not talking about parking tickets here. The big money is in violent crime, especially homicide.

Federal data are crystal clear on one uncomfortable fact:

Black Americans are about 12–13% of the U.S. population.

They consistently account for an outsize share of arrests for murder and non‑negligent manslaughter, and a very high share of other serious violent offenses.

For example (FBI / BJS trends, depending on year):

Black offenders have for years been responsible for roughly half of known homicide offenders, sometimes slightly more, sometimes slightly less, in datasets where race is recorded and offender is known.

Black arrest rates for robbery and certain types of aggravated assault are multiples of the white rate, even after you adjust for age.

You do not get from 13% of the population to ~50% of murder offenders by accident. That is not “a little bit higher.” That’s a radically disproportionate share of the worst, most expensive crime category.

If you stick with our conservative $3T/year total crime cost and allocate the cost of serious violent crime roughly in proportion to the share of serious violent offenders, you immediately get:

If Black offenders are, say, 35–40% of serious violent offenders overall (averaging homicide, robbery, aggravated assaults), then the share of total crime damage associated with that subset is on the order of $1.0–1.2 trillion per year.

Even if you cut that to 30% to be extra cautious, that’s still:

0.30 × $3T ≈ $900 billion per year in crime cost linked, in proportion to offending, to a group that’s ~13% of the population.

Over a 30‑year window?

30 × $0.9–1.2T ≈ $27–36 trillion in cumulative social damage associated with that sliver of the population’s crime, using conservative shares and a mid‑range total cost.

This is not “oppression in the abstract.” This is concrete, widely distributed damage: murdered victims of all races, medical bills, policing bills, traumatized neighborhoods, capital flight.

C) The Prison Bill: Who Fills the Cells?

On top of direct victimization costs, you have what it takes to contain the chaos: police, courts, prisons, parole, public defenders.

Corrections alone:

Best estimates put direct corrections spending (state and federal prisons, local jails, supervision) at about $80 billion per year in budget line items.

When you include ancillary costs (health care, capital, overhead), broader studies estimate the total prison system cost to taxpayers at around $180 billion per year.

Racial composition:

Black Americans are about 33% of the sentenced prison population and an even higher share of some offense categories, despite being only ~13% of the population.

If Black inmates are roughly one‑third of the prison headcount, then the share of prison‑system cost attributable to locking up Black offenders is about:

⅓ × $180B ≈ $60 billion per year.

That figure does not include:

the cost of policing that leads to those arrests,

the court and prosecution system that processes them,

the public‑defender and indigent‑defense apparatus that represents them,

the post‑release supervision costs.

Realistically, once you add policing and courts, the all‑in “crime control” spend is hundreds of billions annually. A sizable fraction of that is driven by crime in heavily Black urban areas.

D) Riots and “Social Justice” Arson

Then you have discrete bursts of mass property destruction dressed up as political protest.

Take the 2020 George Floyd / BLM riots:

Insurance industry data (via Property Claim Services / Aon / others) show the 2020 civil unrest was the most expensive riot event in U.S. history, with over $1–2 billion in insured property losses nationwide.

Insured losses are only part of the picture. Uninsured losses—looted small businesses, smashed vehicles, shuttered local shops, long‑term declines in property values—are at least as large, often larger, but never fully quantified.

If you estimate that:

For every dollar of insured loss, there’s another $1–2 in uninsured loss and long‑run damage to local capital and employment,

then a $2B insured event is easily $4–6B in real destroyed wealth.

That’s one episode.

You can repeat the exercise for:

1960s urban riots (Newark, Detroit, Watts, etc.),

1992 Los Angeles,

Ferguson and Baltimore in the 2010s.

Each wave of unrest:

destroys property concentrated in already fragile neighborhoods,

drives off businesses and insurers,

depresses tax bases,

triggers future public bailouts and “reinvestment” programs.

None of that is free. Every time the glass breaks and the match is lit, the bill lands on the broader society.

E) White Flight, Urban Depopulation, and Bailouts

High crime doesn’t just hurt direct victims; it reshapes entire regions.

Patterns since the 1960s:

Rising crime and disorder in many cities coincided with White (and later middle‑class Black) flight to suburbs and exurbs.

As higher‑earning residents left, city tax bases shrank.

Remaining populations became poorer and more dependent on state and federal transfers.

That produced a cycle:

Crime spikes →

Capital and people leave →

Tax base collapses →

City becomes more dependent on state/federal aid →

Reform efforts are framed as “equity” and “reinvestment,” adding more spending to grief

You can see this in:

NYC’s near‑bankruptcy in the 1970s and subsequent state/federal assistance;

Federal aid packages to distressed cities;

Ongoing streams of HUD, DOJ, and HHS money into “high‑crime, high‑poverty” areas.

Quantitatively:

Even relatively small annual transfers (a few billion per major city) add up over decades to tens of billions of extra subsidy to jurisdictions that became fiscally fragile largely because of crime and disorder.

Those subsidies are financed by taxpayers who stayed put, kept paying their bills, and did not burn down their neighborhoods.

You don’t need exact city‑by‑city numbers to see the logic: high‑crime areas get ongoing bailouts, and those bailouts are part of the total cost of tolerating disorder.

F) The Legal and Defense Subsidy

High violent‑crime rates also create a permanent taxpayer obligation to provide legal defense and incarceration for offenders, who overwhelmingly cannot pay for these services themselves.

Public defender systems in big urban counties handle thousands of cases per year, often with caseloads well above ABA guidelines. These are funded by county and state budgets.

Indigent defense spending in the U.S. is in the billions annually; the majority of serious felony defendants qualify for such representation.

Because arrest and conviction rates are not racially even, Black defendants disproportionately consume these “free lawyer” resources. That is, again, not morally “good” for anyone — it reflects real dysfunction — but fiscally it is yet another stream of state‑funded services consumed at a high rate by a small group.

Add to that:

prison health care,

rehabilitative programs,

re‑entry services,

and the picture is straightforward: a small subset of the population imposes exceptionally high per‑capita costs on all of these systems.

Section VI Ledger Subtotal

We don’t want to double‑count, so we’ll keep this at the level of orders of magnitude and a clear “who pays / who suffers” breakdown.

1. Total crime cost, share reasonably associated with Black offending

Working total crime cost: ≈ $3 trillion/year (mid‑range of existing estimates).

If Black offenders are responsible for ≈ 30–40% of serious violent crime and a significant share of other high‑cost offenses, it is cautious to assign ≈ 30% of total crime costs to that subset.

That yields:

0.30 × $3T ≈ $0.9 trillion per year in social cost linked, in proportion to offending, to a group that is ~13% of the population.

Over 30 years:

≈ $27 trillion in cumulative damage.

Even if you shave that down further, you are nowhere close to “zero.” You are deep into multi‑trillion‑dollar territory.

2. Corrections and crime‑control spending

Total prison‑system cost: ≈ $180B/year.

Black inmates ≈ ⅓ of sentenced population → ≈ $60B/year to cage and manage them.

Add a fraction of policing/court budgets targeted at high‑crime areas and you plausibly get to:

≈ $70–90B/year in crime‑control spending fairly associated with Black offenders.

Over 30 years:

≈ $2.1–2.7T.

3. Riot damage and urban bailouts

2020 unrest alone: ≥ $1–2B insured, likely $4–6B+ total once uninsured losses and long‑term damage are included.

Earlier waves of riots and unrest across the 1960s–2010s add tens of billions more in destroyed property and lost tax base.

Extra state/federal transfers to keep distressed, high‑crime cities afloat compound that bill over decades.

It’s reasonable to treat riot‑driven destruction and related bailouts as another low‑hundreds‑of‑billions in wealth wiped out or shifted to taxpayers.

Conservative bottom line for the crime section of the ledger:

Crime‑related social cost associated, in proportion to offending, with Black offenders since roughly 1990: easily on the order of $20–30 trillion in destroyed wealth and human capital.

Corrections and control costs attached to that subset: another ≈ $2–3 trillion over a similar horizon.

This is not “money paid to Black Americans” in the way welfare is.

It’s worse: it is wealth that never exists anymore because it was burned in gunfire, theft, riots, and the apparatus needed to contain the fallout.

If you’re genuinely doing a national ledger of who has cost whom what, you cannot ignore this column.

Note: We didn’t even include rates of driving without insurance and associated damages.

VII. Fragmentation, Grievance, the Clientelist State

So far the ledger has been about money and damage: trillions in transfers on one side, trillions in destroyed wealth on the other.

But reparations aren’t just a fiscal claim. They’re a political technology: a way of turning race into a permanent entitlement category and taxpayers into a permanent debtor class. Once you do that, you don’t just change who gets checks — you change how the whole system works.

A) Diversity and Trust: Why Group Politics Wrecks Public Goods

Robert Putnam’s famous “E Pluribus Unum” study looked at hundreds of U.S. communities and found something that people who live in real neighborhoods already know:

In the short and medium term, more ethnic diversity is associated with lower trust, less cooperation, and more people “hunkering down.”

In more diverse areas, people trust their neighbors less, participate less in civic life, and are less willing to support broad public goods.

Alberto Alesina and co‑authors ran the numbers at the city/country level and found the same pattern:

Higher ethnic fractionalization → lower spending on broad public goods (infrastructure, schools everyone uses) and more fights over targeted benefits.

In plain language:

The more people feel politics is about “my group vs your group”, the less they’re willing to pay taxes into a common pot.

Instead, they fight to make the state their side’s cash machine.

Now ask what a formal reparations regime does in that environment:

It doesn’t just acknowledge diversity. It locks it into statute as a moral hierarchy:

One ancestry group = official “creditor”

Everyone else = official “debtor”

It takes every budget argument and puts a racial overlay on it: “Have they paid us enough yet?”

Trust doesn’t survive that. Why would it?

B) Once You Create a Creditor Class, It Never Closes the Account

Reparations activists sell their project as a one‑time healing event: pay the check, cleanse the sin, move on.

Everything we know about politics says the opposite will happen:

The moment you write the first check, the check becomes the floor, not the ceiling.

Any finite dollar amount can be called a “down payment.”

Any sunset clause can be framed as “they’re trying to cut us off again.”

The incentive of activists and bureaucrats is to keep the grievance alive.

NGOs, commissions, DEI offices, and university centers will literally exist to keep the story going.

Their budgets, careers, and relevance depend on arguing that whatever was paid is not enough.

Every new social problem gets added to the tab.

Slavery → Jim Crow → redlining → mass incarceration → micro‑aggressions → climate injustice → algorithmic bias → whatever comes next.

The narrative can always stretch to include the latest fashionable grievance as “part of the same debt.”

You don’t get a one-off reconciliation event. You get permanent grievance infrastructure.

C) The Reparations Bureaucracy: A Machine Built to Expand Itself

We’ve already seen a preview of this madness in California.

AB 3121 set up a state reparations task force to study slavery’s legacy and recommend remedies.

After years of hearings, they recommended: