Off-Target Effects in CRISPR Gene Editing

Off-target risks are not much of a concern now... and will be mostly a non-issue in the future.

If you’re considering permanent genetic modification — whether for:

Bioenhancement (upgrading traits, custom character, etc.)

Curing disease

Off-target effects are the safety concern that matters most.

The 60-Second Version

Off-target effects are unintended DNA changes that happen when a gene editor accidentally modifies the wrong spot in your genome.

This article is mainly about off-target risk from permanent DNA editing (base/prime), while briefly explaining how transient tools (circRNA/siRNA) fit as test-drives before you lock anything in.

Most off-targets are harmless. About 70% land in DNA that does nothing. Another 15% occur in cells that die and get replaced naturally. Only about 0.5% could cause real problems.

Technology choice matters enormously. Using the right editor (base or prime) instead of the wrong one (Cas9 nuclease) reduces your risk by 1,000-10,000×.

Body editing is already very safe. With current technology, 10 permanent edits to your liver carry about a 1 in 100 million chance of serious harm.

Brain editing is safe but harder. The brain can’t clear mistakes naturally and you can’t biopsy it to check. Current delivery methods for the brain are suboptimal, but better ones arrive around 2030. Brain delivery limitations mostly affect coverage per session, not whether edits last — edited neurons stay edited permanently.

The risk from editing is millions of times smaller than the risk from aging. A 50-year-old has about a 1 in 50 chance of dying in the next year. Gene editing risk is 1 in 20-200 million.

Key Terms

Before diving in, here’s what the jargon means:

Editor = the molecular tool that changes your DNA. Think of it as the scalpel. There are several types (explained below). The editor is what determines how the change is made and how clean it is.

Delivery vehicle = how you get the editor into your cells. Think of it as the ambulance that carries the scalpel to the operating room. LNPs, AAV, and anellovectors are all delivery vehicles.

These are independent choices. You pick an editor AND a delivery method. Both affect your risk. A clean editor in a bad delivery vehicle still has problems.

Off-target = the editor changed the wrong spot in your DNA. Like a surgeon operating on the wrong vertebra.

On-target = the editor changed exactly what you wanted. The successful surgery.

Transient delivery = the editor enters your cells, does its job in hours to days, then breaks down and disappears. This is what you want.

Persistent delivery = the editor keeps being produced in your cells for months to years. This is bad because the longer it’s active, the more chances it has to make mistakes.

Double-strand break (DSB) = cutting both sides of the DNA ladder completely in half. Dangerous because the repair is messy and can cause permanent chromosome damage.

Safe harbor = a pre-validated location in your genome where new genes can be safely inserted without disrupting anything important. Like an approved parking spot.

Coverage (editing): the fraction of target cells that receive the edit in a given session (e.g., % of neurons edited). Coverage can be increased by additional sessions; this is not “maintenance.”

Transient tool vs permanent result

Transient delivery means the editing tool (the editor protein and its instructions) is only active for 1–3 days, then it degrades and disappears. This is what keeps off-target accumulation low.

Permanent edit means the DNA change that tool made lasts for the life of that cell (and any daughter cells if it divides).

You want both: A tool that works briefly (safer) and leaves a lasting DNA change (useful). Think “contractor for a weekend, renovated house for years.”

Nuances of “redose” (they’re different)

Maintenance redosing (RNA tools): circRNA/siRNA effects fade in weeks–months, so you redose to keep the effect.

Coverage redosing (permanent editing): if one session edits only part of the target tissue, you may do additional sessions to reach more cells. The cells edited in session #1 stay edited permanently.

Expansion redosing: you come back later because you want additional variants edited, not because old edits “wore off.”

Most people should test-drive first (circRNA/siRNA)

Before locking in permanent DNA edits, most people should run reversible trials to learn (a) whether the biology helps them and (b) what side effects feel like.

circRNA: Temporary protein boost (weeks). Does not change DNA, so it has zero DNA off-target risk. Main risks are dose/overexpression effects and delivery reactions (inflammation).

siRNA: Temporary gene knockdown (often months). Also doesn’t change DNA; the main risks are over-silencing and unintended knockdown of similar transcripts (temporary, not permanent DNA change).

Use-case: Try transient tools first, measure outcomes (labs + performance tests), then decide what’s worth locking in permanently with base/prime editing.

Part 1: Why Most Off-Targets Don’t Hurt You

Your DNA is 3.2 billion letters long. When the editor searches for its target, it occasionally finds a spot that looks similar enough to fool it. That’s an off-target.

But here’s what most people don’t realize: your genome is mostly empty space.

Think of it like editing a specific word in a 1-million-page book. If the editor accidentally changes a different word, odds are it changed a word on a blank page that nobody reads.

Here’s the actual breakdown:

~95% of your DNA has no known function. An edit here does nothing. It’s like changing a letter in the margin notes of a book nobody reads.

~1.5% codes for proteins. But you have two copies of almost every gene, and most changes are harmless because one working copy is enough.

~3-4% controls when genes turn on/off. Changes here can matter, but most still don’t cause problems.

~0.03% is truly critical. Tumor suppressors, cancer-related genes, genes where one copy isn’t enough. A hit here is bad.

So when someone says an editor has a “5% off-target rate,” that means 5% chance something gets changed somewhere.

But the chance that change actually hurts you? About 1 in a million or less because almost everywhere it could land is harmless.

Part 2: The CRISPR Gene Editing Tools: Base, Prime, etc.

All modern gene editing comes from CRISPR technology. But there are now several versions, and they have very different safety profiles.

Think of it as the difference between a chainsaw and a scalpel: both cut, but the precision is worlds apart.

Cas9 Nuclease: The Original (Avoid for Enhancement)

This is the first-generation CRISPR tool.

It works by cutting both strands of your DNA completely in half. Your cell then tries to repair the break, but often does it sloppily—inserting or deleting random letters at the break site.

The big problem: If the editor makes two cuts on different chromosomes at the same time, the repair machinery can accidentally join the wrong pieces together. This is called a translocation—a permanent chromosome rearrangement that cannot be fixed with any current or foreseeable technology. Translocations can directly cause cancer.

For enhancement where you might want 20-50 edits, the risk of a translocation happening at least once becomes unacceptable. Don’t use Cas9 nuclease for enhancement.

High-fidelity versions (HiFi Cas9, HypaCas9, etc.) reduce off-target rates but still create double-strand breaks, so the translocation risk remains.

Base Editing: The Current Standard (Recommended)

Base editors use a modified version of the CRISPR machinery that has been deactivated so it can’t cut. Instead, it chemically converts one DNA letter to another while the DNA strand stays intact. No cutting = no translocations.

There are two main types:

ABE (adenine base editor) converts A→G (and the reverse strand T→C). This is currently the cleanest and most reliable editor:

Current version (ABE8e): 0.01-0.1% off-target rate with good guide design

Next-gen (ABE9, arriving ~2028): less than 0.01% off-target rate

Minimal random activity across the genome

Less relevant and problematic:

CBE (older cytosine editors) Converts C→T. It works, but has a problem: it randomly changes C→T letters scattered across your genome at a low rate, even in places nowhere near your target. This unpredictability is why CBE is being phased out for precision work.

Prime Editing: The Most Versatile (Recommended)

Prime editors use a CRISPR component that only nicks one strand (not both) and carries a template that writes new sequence directly. Think of it as molecular “find and replace.”

Prime editing can make any small change: all 12 possible letter swaps, small insertions, small deletions. It’s the Swiss Army knife of gene editing.

Trade-off: Prime editing is less efficient than base editing (10-50% of cells get edited vs 50-90% for base editing), so you might need higher doses or multiple rounds.

Off-target rate: Less than 0.5%, no random genome-wide activity, no double-strand breaks.

Which Editor for Which Job?

Base editors can only do A→G changes.

That covers a lot of beneficial variants, but not all of them.

A realistic enhancement package uses both:

~60-70% of edits use base editing (wherever the needed change is A→G)

~30-40% of edits use prime editing (for everything else)

Table 1: Editing Methods Compared

Cas9 nuclease: The original. Off-targets create messy insertions/deletions plus risk of chromosome rearrangements. Some off-targets are literally unfixable. Avoid for any multi-edit work.

High-fidelity Cas9: Better aim, same fundamental problem—still cuts both strands, still risks translocations. Not good enough for enhancement.

CBE: Can do C→T changes, but scatters random C→T mutations across your genome unpredictably. Being replaced by prime editing for C→T work.

ABE/base editor: Current workhorse. Cleanest profile. Off-targets are simple point mutations that are >90% reversible using the opposite editor. Handles about 60-70% of enhancement edits.

ABE9/next-gen base editor: Same thing but ~10× cleaner. Available around 2028.

Prime editor: Handles everything base editors can’t. Slightly higher off-target rate and lower efficiency, but no translocations and correctable. Handles about 30-40% of enhancement edits.

What Off-Targets Actually Look Like by Editor

Base editor off-targets: A single A→G letter change at the wrong location. Like a typo in a book—usually on a blank page (junk DNA), occasionally in a word that still reads fine (tolerated mutation), very rarely in a word that changes the meaning of a critical sentence (harmful).

Prime editor off-targets: A small, template-defined change at the wrong location. Same logic as base editors—the change is predictable in nature, just at the wrong address.

Cas9 nuclease off-targets: A messy cut that gets repaired with random letters added or removed. Sometimes large chunks of DNA get deleted. Worst case: two cuts on different chromosomes cause a translocation—pieces of your chromosomes get permanently swapped. This is the one outcome that truly cannot be undone.

How Editors Keep Getting Better

Gene editors haven’t stood still. Each generation gets cleaner through protein engineering—modifying the editor’s structure so it grips its target more tightly and ignores similar-looking sequences.

Base Editor Evolution:

ABE7.10 (2017): The original. Proved adenine base editing was possible, but the deaminase enzyme (the part that changes A→G) was slow. The whole complex lingered at off-target sites long enough to sometimes edit them. Off-target rates 0.5-5%.

ABE8e (2020): The deaminase was evolved through testing millions of variants to be much faster—it makes the intended change and moves on before it can act at off-target sites. 10-100× fewer off-targets. This is what most people would use today.

ABE8e + high-fidelity Cas9 (2022): The Cas9 component (the part that finds the target) was also improved. High-fidelity Cas9 variants bind DNA more tightly at the correct target and let go faster at near-matches. Combining a clean deaminase with a tight-binding Cas9 gives the best of both.

ABE9 (emerging ~2028): Next-generation engineering using machine learning to predict which protein modifications improve specificity. Expected to be ~10× cleaner than ABE8e.

ABE10+ (projected ~2032): Approaching the physical limits of how precisely a protein can distinguish its target from similar sequences.

Prime Editor Evolution:

PE2 (2019): Proved prime editing works. Low efficiency (5-30% of cells successfully edited) limited practical use. Needed large doses, which increased off-target exposure.

PE4/PE5 (2022): Manipulated DNA repair pathways to favor the prime edit. Efficiency jumped to 15-50%. Made prime editing practical for therapeutic use.

PE6/PE7 (2024-2026): Optimized the reverse transcriptase and nicking strategy. Efficiency reached 30-60%, meaning lower doses needed and less off-target exposure.

Next-gen (~2030): Expected to close the efficiency gap with base editors (50-80% editing rates). Combined with AI guide design, off-targets should drop below 0.1%.

The pattern: Each editor generation achieves roughly 10× improvement in off-target rates through better protein engineering (tighter binding), faster catalysis (less time at each site), and AI guide design (avoiding problematic sequences entirely).

Part 3: Getting the Editor into Your Cells

The editor (base or prime) is the tool. But you need to get that tool inside the right cells in your body. That’s what delivery vehicles do.

Why This Matters for Off-Targets

The single most important factor is how long the editor stays active in your cells. A surgeon who operates for 30 minutes has fewer chances to make a mistake than one who operates for 30 days.

Transient delivery (mRNA): Your cells get instructions to build the editor. They build it, it works for 1-3 days, then the instructions (mRNA) break down naturally and editor production stops. This is what you want.

Persistent delivery (DNA via AAV): Your cells get permanent instructions (DNA) to build the editor. They keep building it for months to years. The editor keeps searching your genome, finding more and more off-target sites. This is bad.

Nobody wants persistent editor activity.

It’s a limitation of certain delivery methods, not a feature.

The editor itself (base or prime) is the same either way—the problem is that DNA-based delivery won’t stop producing it.

Self-limiting editors (discussed later) are basically a backup brake for the rare cases where delivery isn’t perfectly transient.

Table 2: Delivery Methods Compared

LNP (lipid nanoparticle): Tiny fat bubbles that fuse with your cells and release mRNA inside. The mRNA tells your cells to make the editor for 1-3 days, then it degrades. Currently the most mature delivery method for liver. Brain-targeted versions are emerging: one formulation achieves 7-16% of neurons reached via simple IV injection. Some immune response means repeat dosing may be limited.

Anellovector: Derived from viruses that naturally live in your body without causing disease. Can carry mRNA for transient expression. Major advantage: your immune system doesn’t attack them, so you can dose as many times as needed. Can target brain. Clinical trials starting 2025-2027.

Exosomes: Tiny bubbles naturally released by cells. Can be loaded with editor mRNA or pre-made editor protein. Naturally cross the blood-brain barrier. Low immune response. Limitation: hard to control where they go, currently inconsistent results.

Virus-like particles (VLPs): Viral shells without any viral DNA inside. Combine the delivery efficiency of viruses with non-viral safety. Can carry mRNA or protein. Emerging technology.

Polymer nanoparticles: Synthetic particles (various materials) that can be customized for different tissues. Biodegradable, redosable. Currently less efficient than LNPs but improving.

A Warning About AAV-Based Editing

You may encounter clinics or researchers proposing to use AAV (adeno-associated virus) to deliver gene editors to the brain. Probably smart to avoid entirely.

AAV delivers DNA, not mRNA. DNA persists in your cells for months to years. This means the editor keeps being produced and keeps scanning your genome long after it’s finished making your intended edits. It’s like leaving the surgeon in the operating room for six months after the procedure—nothing good comes from extra time with a scalpel.

AAV is well-established for traditional gene therapy (delivering a missing gene for hemophilia or blindness), where persistent expression is actually the point—you want the therapeutic protein produced forever. But for gene editing, you want the editor to work quickly and disappear. AAV can’t do that.

Nuance: AAV can still make sense for gene addition (a permanent factory to produce a helpful protein), but for gene editing machinery you generally want hit-and-run expression.

Problems with AAV for editing:

20-50× more off-target accumulation compared to transient delivery

50-78% of people develop antibodies after the first dose, blocking future treatments

If you need more edits later, you may be locked out

Bottom line: If a provider suggests AAV for delivering a gene editor, ask why they aren’t using transient mRNA delivery instead. If they don’t have a good answer, find a different provider. The only legitimate reason to consider AAV for brain editing in 2026 is that transient brain delivery options aren’t fully mature yet—but that’s an argument for waiting a few years, not for accepting worse technology.

By ~2030, transient mRNA delivery to the brain (via anellovectors, brain-targeted LNPs, and other emerging vehicles) should be mature enough to avoid AAV entirely.

Brain Delivery: Multiple Options Exist

LNPs are not the only way to reach the brain. Several platforms are being developed:

Brain-targeted LNPs: Special lipid formulations that cross the blood-brain barrier. Currently 7-16% of neurons reached. Projected 40-60% by 2035. These should be interpreted as “coverage per session.” Each neuron stays edited permanently; repeating sessions simply reaches more neurons.

Anellovectors: Being developed for brain applications. Redosable, which is critical for phased editing.

Engineered exosomes: Natural blood-brain barrier crossing ability. Being optimized for consistency.

Focused ultrasound + systemic delivery: Temporarily opens the blood-brain barrier in a targeted region, letting standard delivery vehicles through. Already in clinical use for other purposes.

Direct injection: Invasive but precise. Used for localized brain conditions.

Which Delivery Gets the Best Results in Target Cells?

Not all delivery methods are equal in how many target cells actually get edited:

Liver via LNP-mRNA: The gold standard for in vivo editing. Simple IV injection. LNPs naturally home to the liver. 40-70% of liver cells edited in a single session. Editor works for 1-3 days then disappears. Can redose if needed.

Blood stem cells via electroporation: Cells removed from body, electrical pulses open pores, pre-made editor protein enters. 80-95% editing efficiency. The best results of any approach because you’re working with cells in a dish, not inside a body.

Brain neurons via brain-targeted LNPs: Emerging. Currently 7-16% of neurons reached via IV injection. By 2035, optimized formulations plus anellovectors may reach 40-60%. Multiple sessions can increase total coverage.

Muscle via direct injection: Inject editor directly into muscle. Reaches 20-40% of local fibers. Systemic muscle delivery is harder—muscle-targeting vectors are in development.

Skin via direct/topical: Local delivery reaches 30-50% of target cells. Topical formulations being developed.

Part 4: Your Edits Are Permanent (And That’s the Point)

Permanence Is the Goal

If you’re doing somatic gene editing for enhancement, you want permanent changes. That’s the whole point. If you wanted temporary effects, you’d use circRNA or siRNA, which fade in weeks.

When you edit with base or prime editors, the DNA change is permanent in every cell that receives it. A neuron edited today carries that change for your entire life. A liver cell edited today carries it until that cell naturally dies (roughly 3 years on average, but its replacement cells from the progenitor pool may also carry the edit if those were targeted too).

Where to Edit for Lasting Results

For your enhancement to stick, the editor needs to reach the right cells:

Liver cells: The easiest target for in vivo editing. LNPs naturally accumulate in the liver. Hepatocytes self-renew, so your edit persists for years. The liver also produces secreted proteins that affect your whole body, making it a strategic target for metabolic enhancement.

Blood stem cells: Currently done ex vivo—stem cells are removed from your body, edited in a dish, and returned. This is how sickle cell gene therapy works. One-time treatment, lifetime effect. All blood and immune cells descend from these stem cells, so one edit propagates everywhere.

Brain neurons: The ultimate permanent edit. Neurons never divide, never get replaced. Edit once, changed forever. The challenge is getting the editor through the blood-brain barrier.

Muscle fibers: Very low turnover. Direct injection reaches 20-40% of local fibers. Satellite cells (muscle stem cells) should also be targeted for complete durability.

Heart muscle cells: Similar to muscle—very low turnover, edits are essentially permanent. Hard to reach with current delivery.

Skin basal cells: The regenerative layer. If you hit these, their descendants (the surface cells) all carry your edit as they’re produced. Surface cells shed every 2-4 weeks but are constantly replaced by edited basal cells.

Intestinal stem cells: Deep in the gut lining. If you edit these, every new gut surface cell carries your edit. The surface cells turn over every 3-5 days, but the stem cells persist for life.

The Off-Target Bonus in Fast-Turnover Tissues

Here’s where tissue turnover becomes relevant—not for your intended edit (which targets long-lived cells), but for off-targets in bystander cells.

When the editor is delivered to your liver, most of it reaches liver cells (the target). But some may hit nearby short-lived cells. Any off-target in a short-lived cell dies with that cell within days to weeks. Nature cleans up the mistake automatically.

Fast-turnover tissues have a built-in safety net: off-targets in bystander cells get cleaned up for free. Brain neurons don’t have this safety net—off-targets there are permanent. This is one reason brain editing requires higher precision, not because the edits are different, but because there’s no forgiveness for mistakes.

Part 5: How Bad Can Off-Targets Be?

Most Are Nothing. A Few Matter. Very Few Are Serious.

Silent (~70%): The vast majority. Lands in the 95% of your genome that does nothing. You’d never know it happened without deep sequencing. Zero consequence.

Self-clearing (~15%): The off-target is in a cell that’s about to die anyway. Gut cells last 3-5 days, skin cells 2-4 weeks. The cell dies, gets replaced by a fresh one without the off-target. Problem solved by your body’s natural maintenance.

Tolerated (~10%): Lands in a gene, but the change doesn’t break anything. Maybe it changed a DNA letter but the protein still reads the same way (like changing “colour” to “color”—same meaning). Or maybe the protein is slightly different but still works fine.

Manageable (~4%): Actually disrupts a gene’s function. But you have two copies of most genes, and for most genes, one working copy is enough. The cell functions normally. If you detect it and want to fix it, a reverse editor (delivering the opposite base editor) works >90% of the time.

Serious (~0.9%): Disrupts a gene where you really need both copies working (called haploinsufficient genes). Could cause subtle dysfunction. Should be corrected if found.

Severe (~0.09%): Hits a tumor suppressor or activates an oncogene. This sounds terrifying, but important context: a single hit is not enough to cause cancer. Cancer requires 3-7 specific mutations in the same cell, accumulated over 10-30 years. An off-target provides one possible “first hit” in a process that still needs several more unlucky events to complete. Still worth monitoring with standard cancer screening.

Catastrophic (less than 0.01%): Translocation. This is the worst-case scenario and it’s completely preventable by not using Cas9 nuclease. Base and prime editors don’t cut both DNA strands, so they physically cannot cause translocations. If you use the right tools, this risk is zero.

When Would You Actually Notice a Problem?

If an off-target causes harm, it doesn’t all show up at once:

Acute gene disruption: If an off-target breaks a gene your cells need immediately, you’d know within days to weeks. Blood tests would show abnormalities. This is the easiest to catch and potentially correct early.

Immune/inflammatory reaction: If cells are stressed by the editing, your immune system responds. Detectable through standard blood tests for inflammation.

Metabolic dysfunction: If a liver enzyme gets disrupted, problems accumulate gradually. Routine metabolic blood panels would catch it within weeks to months.

Neurological effects: If a brain edit causes an off-target in a neuron affecting cognition or mood, you might notice subtle changes over weeks to months. Cognitive testing and brain imaging can track this.

Pre-cancerous cell growth: A cell with a growth advantage slowly outcompetes its neighbors over years. Detectable by periodic DNA sequencing of accessible tissues. May never progress to actual cancer.

Cancer: Even if an off-target provides the “first hit,” clinical cancer takes 10-30 years and 3-7 total mutations to develop. Standard cancer screening would catch it at the same rate as any other cancer—the off-target doesn’t make it invisible or unstoppable.

The reassuring takeaway: If you get through the first year with normal blood work and no symptoms, the remaining long-term risk is dominated by the extremely slow cancer pathway—which requires multiple additional unlucky events beyond the initial off-target.

Part 6: Detection and Monitoring

What’s Available Now (2026)

Before you get edited, the clinic tests the editing tools on cells in a dish to identify problematic off-target sites. This catches most issues before they ever reach your body.

After editing, detection depends on the tissue:

Body tissues (liver, blood): Can biopsy and sequence DNA. Current methods detect off-targets present in at least 1 in 10,000 cells.

Brain: Cannot biopsy. Can analyze spinal fluid for traces of neuronal DNA, but sensitivity is only ~0.1%—catches major problems but misses rare events.

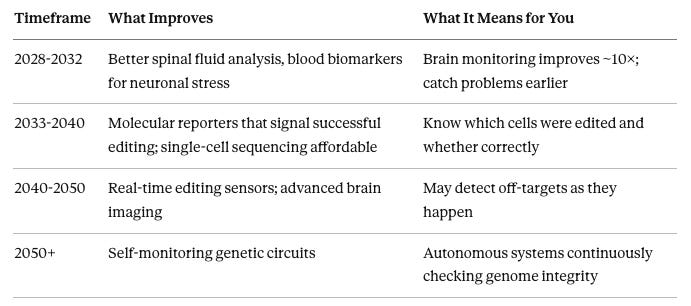

What’s Coming

Watermarking Your Edits

Every edit could be watermarked: Silent DNA changes placed near your intended edits that serve as unique identifiers. Decades later, if health issues arise, sequencing can determine whether a mutation came from your gene editing or from natural background processes (your cells accumulate ~40 random mutations per year anyway).

Risk from watermarks: Essentially zero. They use synonymous changes—different DNA spelling, identical protein.

Part 7: Fixing Mistakes

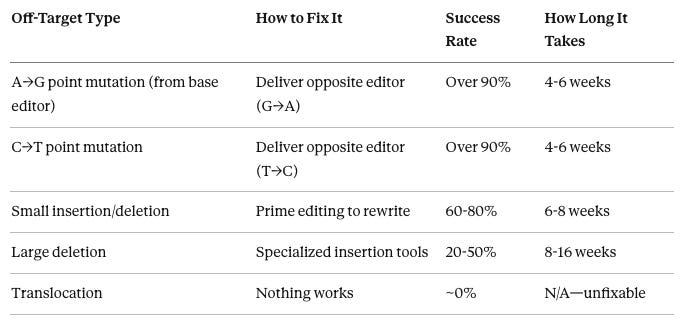

Can Off-Targets Be Corrected?

Yes, most of them. The basic idea: if a base editor made an unwanted A→G change, deliver the opposite base editor (which converts G→A) to that specific site.

Point mutations (single letter changes): Highly fixable. Design a guide targeting the off-target site, deliver the reverse editor with transient delivery, verify correction. Over 90% success rate. This is why base/prime editors are preferred—their off-targets are the kind you can actually undo.

Small insertions/deletions: Prime editing can rewrite the original sequence. Lower success rate (60-80%) because it depends on the local DNA context.

Large deletions: Challenging. Need specialized tools to re-insert missing DNA. Success rates 20-50%.

Translocations: Cannot be fixed. Chromosomes have been rearranged—you’d need to re-cut and re-join them perfectly in millions of cells simultaneously. Not feasible with current or foreseeable technology. This is the primary reason to never use Cas9 nuclease for enhancement.

Body vs Brain Correction

Body (liver, blood, etc.): Biopsy the tissue → sequence to find exactly where off-targets occurred → design reverse editors → deliver via transient method → biopsy again to verify correction. End-to-end success: ~90-95% for point mutations. Timeline: 3-6 months.

Brain: Can’t biopsy to find specific off-targets. Can’t verify correction at the molecular level. Instead: deliver reverse editors broadly across the edited brain region → measure functional outcomes (cognitive tests, imaging, EEG). You’re correcting blind—measuring results rather than confirming at the DNA level. Success: ~70-85% functional improvement. Timeline: 6-12 months.

Future Correction Technology

2030-2035: Bridge recombinases—a new class of tools that can recognize and revert specific sequences. Currently ~20% efficient but improving rapidly. Could enable more precise brain correction.

2040-2050: Self-correcting genetic circuits that automatically detect and fix off-target changes. May work continuously without external intervention.

2050+: Genome maintenance as routine healthcare—periodic monitoring with automated correction.

Can You Fully Reverse All Edits in the Future?

If you want to go back to your pre-modification DNA: about 90-95% reversal is likely achievable by ~2045.

Never 100%, because some neurons will be missed, and any secondary changes (like new neural connections formed during the enhanced period) won’t be undone by reverting the DNA.

Part 8: Safe Harbors (For Adding New Genes, Not Editing Existing Ones)

Most enhancement edits change existing variants in your DNA—swapping one letter for another at a specific location. Base and prime editors handle this directly at the gene’s natural location.

But some enhancements require adding entirely new genetic material: a longevity gene cassette, a synthetic metabolic pathway, or a protective gene you don’t naturally have. You can’t just insert new DNA anywhere—landing in the wrong spot could disrupt an existing gene or activate a cancer pathway.

Safe harbors are specific locations in your genome that have been validated as safe insertion sites. Think of them as pre-approved parking spots: plenty of room, no interference with traffic, easy to find.

AAVS1: The most commonly used safe harbor. Located inside a gene called PPP1R12C on chromosome 19. Inserting DNA here disrupts that gene, but people function fine without it. Provides reliable, stable expression. Well-characterized in hundreds of studies.

CCR5: The gene encoding a receptor that HIV uses to enter cells. About 10% of Europeans naturally carry a deletion here and are resistant to HIV with no health downsides. Bonus: disrupting CCR5 while inserting your gene gives you HIV resistance as a side effect.

ROSA26: Supports strong, ubiquitous gene expression without disrupting critical functions. Less extensively validated in humans than AAVS1 or CCR5, but growing evidence base.

What goes at safe harbors:

Longevity gene cassettes (extra copies of protective genes like TERT, FOXO3)

Synthetic metabolic pathways

Molecular sensors or reporter genes for monitoring

Therapeutic genes for conditions where you’re missing a gene entirely

Tools for safe harbor insertion:

PASTE: Uses a combination of CRISPR and integrases to insert large DNA at specific locations

eePASSIGE: Uses prime editing to create a landing pad, then inserts the cargo

Why not put everything at safe harbors?

For common variant editing (which makes up most enhancement work), editing the native gene directly is simpler, more efficient, and carries less risk than inserting a whole new gene copy at a safe harbor.

Safe harbors involve larger DNA insertions, which means more things can go wrong with expression levels and unexpected interactions. Use them when you need to add something new, not when you can just change what’s already there.

Part 9: Future Technology Improvements

Off-target rates are already low and dropping fast. Here’s what’s improving:

Near-term (now through 2035):

AI-designed guides: Machine learning models screen every guide before use, filtering out any with significant off-target risk. By 2030, every guide pre-validated to less than 1 in 100,000 off-target probability at any given site.

Better editor proteins: Each generation ~10× cleaner (see editor evolution tables above).

Self-limiting editors: Engineered to shut themselves down after a short activity window (time or edit-count), even if delivery lasts longer than intended. Why this matters: it caps worst-case off-target accumulation if something goes wrong with expression control. In enhancement-style in vivo editing, it’s a safety backstop—not a reason to keep editors active for months.

Medium-term (2035-2050):

Cell-type-specific editing: Editors that only activate in specific cell types. If it’s designed for neurons, it does nothing in liver cells that accidentally receive it.

Real-time quality control: Molecular sensors that detect off-target events as they happen and can trigger cell death in affected cells before damage propagates.

Bridge recombinases (early stage): A non-CRISPR class of tools that may enable specialized sequence-level changes with different error modes than CRISPR editors. They’re experimental and more likely to become niche correction tools than replace base/prime in the near term.

Long-term (2050-2100):

Self-correcting genetic circuits: Autonomous systems that continuously monitor your genome and fix any unwanted changes, including off-targets.

Synthetic chromosomes: Adding an entirely new, artificial chromosome to carry enhancement genes—avoiding modification of your natural DNA altogether.

Genome maintenance as a service: Regular checkups that include genomic integrity scanning and automated repair.

There’s a Physical Limit

No matter how good the technology gets, there’s a thermodynamic floor—a fundamental limit to how precisely any protein can recognize a specific DNA sequence at body temperature. That floor is roughly 1 in 10 million to 1 in 100 million off-target rate per guide. We’re currently within about 100-1,000× of that limit with the best editors.

Further improvement beyond that floor will come from paradigm shifts (self-correcting circuits, synthetic chromosomes) rather than making existing editors more precise.

Part 10: How Safe Is This, Really?

How much should you worry about gene edits in the future?

Risk Per Edit

When this article says “risk per edit,” it means the chance that a DNA change caused by the editing act (mostly off-targets, plus rare on-target surprises) leads to serious harm.

It does not include generic procedure risks (e.g., infusion reactions), which depend more on clinic/setting than on the editor.

With transient delivery, the editor is active for days; any downstream consequence may appear later, but the risk comes from what happened during that brief window—not from the editor continuing to operate for years.

Base editor, transient delivery, 2026: Current-generation base editor (ABE8e) delivered via LNP or anellovector carrying mRNA. Editor enters cells, works for 1-3 days, degrades. Per-edit serious harm: about 1 in 1 billion. This is the safest available option for A→G changes today.

Prime editor, transient delivery, 2026: Current prime editor delivered the same way. Slightly more complex mechanism, slightly higher off-target rate. Per-edit serious harm: about 1 in 500 million. Still extraordinarily safe. Necessary for changes that aren’t A→G.

Next-gen editors (2030-2035): About 10× cleaner per generation. Combined with AI guide design, per-edit risk drops to 1 in 5-100 billion. By 2030, transient brain delivery (anellovectors, brain-targeted LNPs) should be mature, so brain editing achieves the same low rates as body editing.

Future editors (2040+): Approaching the physical limits of DNA recognition specificity. Per-edit risk drops to 1 in 100 billion to 1 trillion. At this level, off-target risk is negligible for any realistic number of edits.

Risk for Actual Enhancement Scenarios

Here’s what real-world edit packages look like, with cumulative risk:

Longevity stack (body) 2026: 10 permanent edits to metabolic and longevity variants (cholesterol genes, inflammation genes, etc.). About 7 edits done with base editor, about 3 with prime editor. Both delivered via lipid nanoparticles carrying mRNA to the liver. Editor works for 1-3 days, then disappears. Total serious harm risk: about 1 in 100 million. Your annual risk of dying in a car accident (1 in 10,000) is 10,000× higher. Proceed with confidence.

Longevity stack (body) 2030: 15 permanent edits using next-generation editors (~10× cleaner). Same delivery method. Total risk: about 1 in 650 million. Approaching lottery-winning territory. Very safe.

Cognitive upgrade (brain) 2030: 10 permanent edits using next-gen editors delivered via anellovector carrying mRNA. This is the game-changer: transient delivery to the brain. Editor works for 1-3 days, then gone. Brain editing now has the same low off-target profile as body editing. Total risk: about 1 in 100 million. Same as 10 body edits in 2026. Safe: proceed.

Cognitive upgrade (brain) 2035: 20 permanent edits using further-improved editors delivered via optimized brain-targeted LNPs carrying mRNA. Coverage reaches 40-60% of neurons. All transient. Total risk: about 1 in 50 million. Safe: proceed.

Full optimization (body + brain) 2035: 35 permanent edits total—15 longevity/metabolic for the body plus 20 cognitive for the brain. Mix of base editing (~65%) and prime editing (~35%). Body edits via LNP-mRNA. Brain edits via brain LNP or anellovector, both carrying mRNA. All transient delivery. Total risk: about 1 in 40 million. For context, a 50-year-old has about a 1 in 50 chance of dying in the next year just from normal aging. The editing risk is nearly a million times smaller. Safe for adults over 40.

Comprehensive optimization 2040: 50 permanent edits using next-gen editors with transient delivery everywhere. About 70% base editor, 30% prime editor. Total risk: about 1 in 200 million. Safe for most adults.

Putting It in Perspective

Dying this year (age 50): A healthy 50-year-old has roughly a 1 in 50 chance of dying in the next 12 months from all causes—heart disease, cancer, accidents, everything. This is the baseline you’re already living with.

Getting cancer in your lifetime: About 40% of people will develop cancer. That’s 1 in 2.5. This is the background risk you carry every day.

Dying in a car accident this year: About 1 in 10,000. Most people drive without thinking about it.

Getting struck by lightning this year: About 1 in 1.2 million. Gene editing with transient delivery is much safer than this.

Dying on a commercial flight: About 1 in 11 million per flight. Nobody worries about this.

35 body + brain edits, 2035: About 1 in 40 million. Comprehensive optimization with mature technology. Safer than a single commercial flight.

10 body edits, 2026: About 1 in 100 million. Metabolic/longevity optimization with current technology. 10,000× safer than driving for a year.

Winning Powerball: About 1 in 292 million. By 2030, a 15-edit longevity stack approaches this territory.

The bottom line: Gene editing risks fall somewhere between “dying in a plane crash” and “winning the lottery.” These are events so unlikely that rational people don’t factor them into decisions. Meanwhile, the things you’re trying to prevent—aging, cancer, dementia—have odds of 1 in 2 to 1 in 50.

Part 11: When to Move Forward

Decision Framework

Age 50+: Your baseline mortality risk (~2% per year) dwarfs any editing risk by a factor of a million. Body editing should be done as soon as variants are validated. Brain editing with 5-10 variants is reasonable now; expand after 2030 when transient brain delivery arrives.

Age 35-50: Body editing is ready now. For brain, you can afford to wait 3-5 years for transient delivery, which drops brain risk by 20-50×. Unless you’re experiencing cognitive decline, the wait is worth it.

Age 20-35: Body editing is ready now. Brain editing improves significantly by 2035. With decades of life ahead, you benefit most from waiting for better technology and more safety data.

Cognitive decline at any age: The trajectory without intervention is bad. Off-target risk is justified by the potential to halt or reverse decline. Proceed with the best available technology.

What the Real Bottlenecks Are

By 2035, off-target safety will be essentially a solved problem for both body and brain. The actual limiting factors will be:

Do these edits actually work in adults? Most genetic research is on populations, not individuals. Validating that specific variants deliver the expected benefits when edited into adult cells is still underway.

What is the potency relative to cost? Not all will have same magnitude of cellular uptake especially in the brain.

Where can you legally get this done? Regulatory frameworks for enhancement editing don’t exist in most countries yet.

Who can afford it? Comprehensive editing will be expensive initially.

Which combinations are optimal? The interaction between 30+ variants is poorly understood.

Safety fades as the primary concern. The harder questions are biological, regulatory, and economic.

Practical way to proceed

Step 1 (test-drive): Use circRNA/siRNA to probe whether changing a pathway helps you and what side effects feel like. This has no DNA off-target risk but requires maintenance dosing.

Step 2 (lock-in): If the benefit is real and worth permanence, use base/prime editing with transient delivery so the editor is active briefly but the DNA change is permanent.

Step 3 (brain reality): Expect coverage to be partial per session; additional sessions increase coverage, not “maintenance.”

Step 4 (monitor + correct): Do sequencing where possible (body tissues), and keep a correction plan (reverse editing) for the rare meaningful off-target.

With the right tool choices (base/prime + transient delivery), off-target risk becomes small enough that the dominant questions shift from “is this safe?” to “which edits actually work for adults, and which are worth locking in?”