The Inverse Deepfake Effect and Liar’s Dividend: When Real Evidence Gets Dismissed as AI

How the existence of deepfakes has triggered a population-level skepticism that makes real events deniable.

A few years ago, the deepfake fear story was straightforward: someone could fabricate a convincing clip of you—your face, your voice, your gestures—and distribute it at internet speed.

That risk remains very real. In early 2024, an Arup employee in Hong Kong was persuaded to transfer roughly HK$200 million (about $25 million USD) after joining a video call that appeared to include senior executives—but the “colleagues” on the call were AI-generated impersonations.

Around the same time, AI-generated robocalls mimicking then-President Biden’s voice urged New Hampshire Democrats to skip the state’s January primary and “save your vote for November” — a straightforward attempt at voter suppression by impersonation.

These are textbook deepfake harms: fabricated evidence deployed to deceive.

But the deepfake story was never only about fabrication. The same technological reality that makes convincing fakes possible also makes something else possible—and this second effect has received far less attention:

The more believable synthetic media becomes, the easier it is to dismiss real evidence as synthetic.

The Inverse Deepfake Effect (Deepfake Doubt Reflex)

This is what I call the inverse deepfake effect:

An ambient, preemptive population-level skepticism toward audiovisual evidence that emerges as a direct psychological response to the existence of deepfakes. It operates like an immune response—people have developed antibodies against fabricated media. But like any immune response, it can overshoot and start attacking healthy tissue.

As synthetic media becomes more plausible, the burden of proof quietly flips: instead of “prove it’s fake,” the default becomes “prove it’s real.”

To be precise about what I’m describing, I want to distinguish between the broader phenomenon and a specific tactical application of it:

The Inverse Deepfake Effect (the umbrella phenomenon): A population-level trust inversion where awareness of synthetic media creates ambient doubt. People increasingly default to “maybe it’s AI” when encountering surprising, inconvenient, or outlandish media—even without any coordinated disinformation campaign. This is an organic psychological adaptation to the existence of deepfakes.

The Liar’s Dividend (a specific scenario within the umbrella): The strategic benefit someone gains by exploiting that ambient doubt. When a politician, corporation, or public figure claims authentic evidence is “AI-generated” or “a deepfake” to evade accountability, they’re harvesting the inverse deepfake effect for personal or institutional benefit.

The term “liar’s dividend” was introduced by legal scholars Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron in their 2019 California Law Review article on deepfakes. They argued that deepfakes wouldn’t only enable new lies—they would also make denials of real events more credible by degrading public trust in audiovisual evidence.

What I’m adding is the recognition that the inverse deepfake effect is broader than strategic exploitation. Much of it is organic: ordinary people, institutions, and even AI detection tools are now generating false rejections of authentic media—sometimes with devastating consequences for innocent parties.

Why This Emerged: The Cognitive and Structural Forces

The inverse deepfake effect didn’t materialize from nowhere. It’s the product of converging psychological, informational, and infrastructural forces.

1. Humans Cannot Reliably Detect Deepfakes—and We’re Overconfident About It

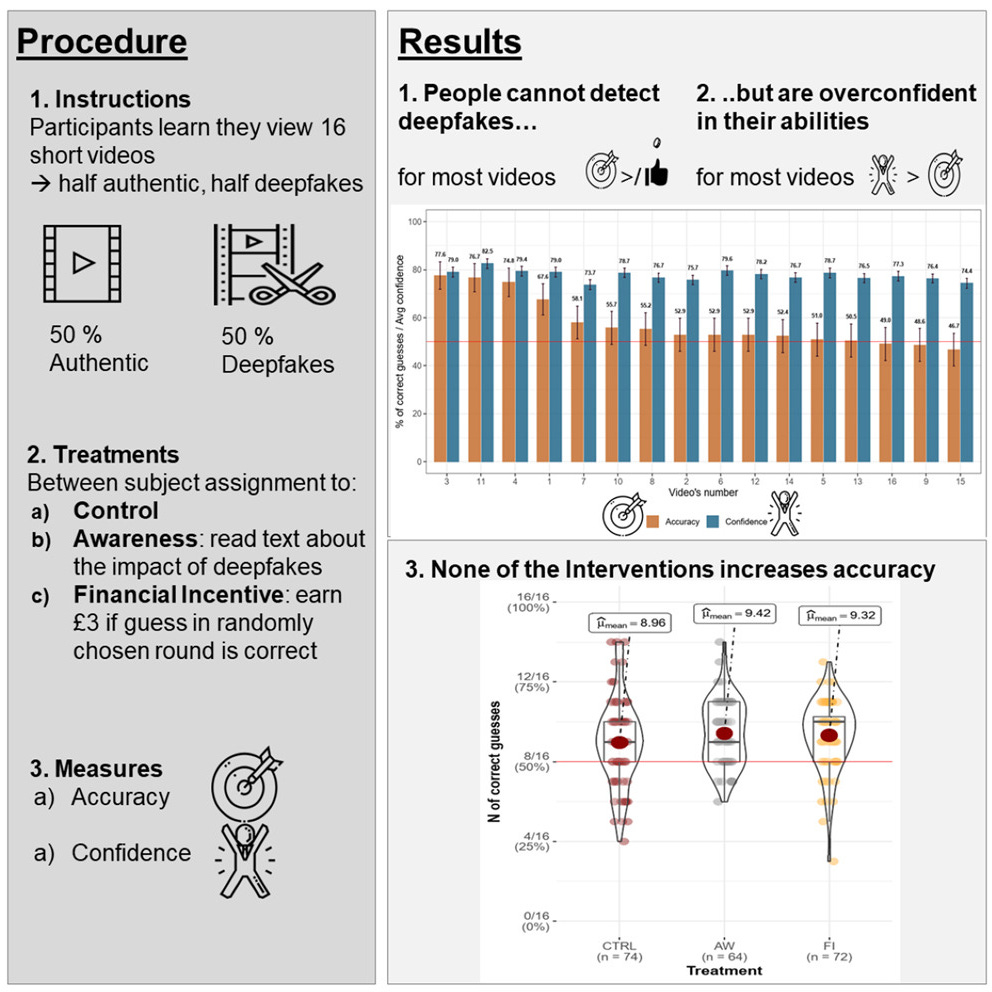

One of the most destabilizing ingredients is that people genuinely struggle to identify deepfakes while believing they’re better at it than they are. A 2021 study published in iScience found that participants performed poorly at deepfake detection and tended to mistake deepfakes as authentic—while simultaneously overestimating their own detection ability.

This creates the worst possible combination: people aren’t competent to verify, but they feel entitled to certainty anyway. That psychological gap produces both kinds of error: credulity when something feels real, and reflexive cynicism when something feels too convenient.

2. Deepfake Awareness Spills Over Into Generalized Distrust

Exposure to deepfakes doesn’t stay neatly targeted. It can shift how people evaluate all subsequent media.

A 2023 study in Telematics and Informatics found that exposure to deepfakes can shift how people judge news accuracy—evidence that deepfake encounters prime broader skepticism beyond the specific content in question.

This is the “immunity” intuition—except immunity can become autoimmune disease. The skepticism overshoots.

3. Public Understanding Is Uneven, Making Uncertainty the Default

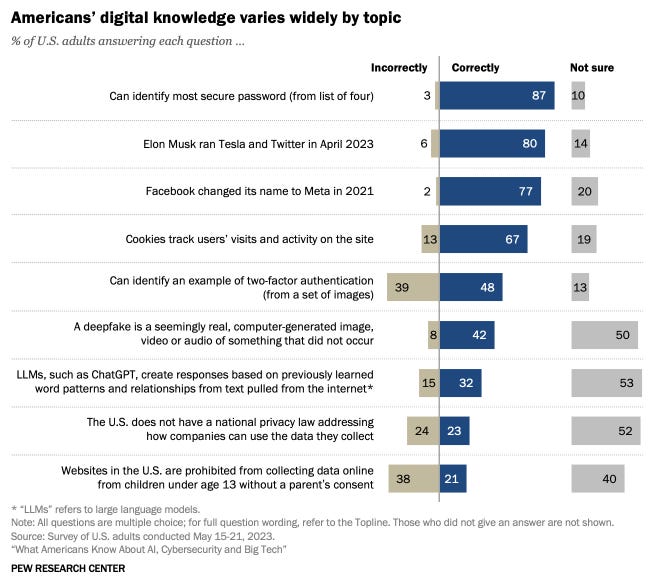

If many people don’t feel confident about what deepfakes are or how they work, “maybe it’s AI” becomes a low-effort cognitive resting point.

Pew Research’s 2023 digital knowledge survey found that only 42% of U.S. adults correctly identified what a deepfake is, and there’s a substantial education gap: 57% of college graduates could define “deepfake” versus 28% of those with a high school diploma or less.

In an environment where many people don’t feel competent to validate authenticity, ambient skepticism becomes rational—even when it leads to false rejections.

4. Denial Is Cheap; Proof Is Expensive

This is the structural asymmetry that makes the inverse effect scale:

It costs almost nothing to say: “That’s AI.”

It can cost a great deal to prove authenticity: original files, metadata, chain of custody, witness corroboration, forensic analysis, institutional credibility.

And the infrastructure often fails to preserve authenticity signals. In October 2025, The Washington Post tested Content Credentials metadata by embedding provenance data into an AI-generated video and uploading it to eight major platforms.

The result: the platforms stripped the provenance marker, and only YouTube surfaced any indication (tucked into the video description) that it wasn’t real.

If platforms don’t preserve authenticity signals, public doubt becomes adaptive—even when it’s socially corrosive.

5. AI Detection Tools Generate False Positives

Adding another layer of complexity, the tools designed to identify AI-generated content are unreliable and frequently mislabel authentic media as synthetic.

This has become particularly consequential in conflict zones, where real documentation of atrocities can be dismissed based on faulty detector outputs.

NIST’s 2024 report on synthetic content risk reduction explicitly acknowledges the limitations of current detection approaches and the challenge of maintaining reliability as generation techniques improve.

The Inverse Deepfake Effect in Practice: Case Studies

If this phenomenon is real, it should show up in documented cases where authentic media is rejected, dismissed, or falsely labeled as AI-generated. It has—across multiple domains.

Geopolitical Conflicts

Russia-Ukraine War

Scope note: Alongside AI-generated media, conflicts also produce other manipulation patterns (recycled/miscaptioned clips, selective edits, reenactments, and occasional staged scenes). When staging is later revealed, that proof can be overgeneralized to dismiss unrelated authentic footage. That’s distinct from what I mean by the inverse deepfake effect: the population-level “maybe it’s AI” reflex that lowers trust in real documentation even when the media is genuine.

Russia–Ukraine has become a laboratory for both deepfake attacks and inverse-deepfake denial.

Attack example: In March 2022, Reuters reported on a deepfake video purporting to show Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy urging his forces to surrender. The video was quickly identified as synthetic and removed by Meta—but it demonstrated how deepfakes could be weaponized in active conflict.

Denial example: Throughout the war, Russian-aligned narratives have pushed debunked claims that evidence of civilian killings and war crimes is “staged” or “fabricated.” One concrete case: VOA documented a Russian diplomat circulating a fabricated “behind-the-scenes” clip to claim the Bucha killings were staged. Even when the word “deepfake” isn’t used, the move is the same — manufacture doubt about documentation to raise the burden of proof and blunt accountability.

Israel-Gaza Conflict

The October 2023 Hamas attacks and subsequent Israeli military operations in Gaza produced massive volumes of documentation—and with it, a second-order problem: the weaponization of “AI doubt.”

This is the inverse deepfake effect in practice: real documentation gets filtered through shaky verification tools and comes out fake in the public mind.

Attack example: Wired reported in late 2023 that generative AI’s role in Israel-Hamas disinformation was “more subtle” than a flood of machine-made imagery—but still consequential.

Inverse example: More troubling was the use of unreliable AI detectors to discredit authentic war footage. 404 Media reported how online AI image detectors were labeling real photographs from the conflict as fake, describing this as a “second level of disinformation.”

France 24’s Observers similarly addressed cases where authentic war-related images were being labeled AI-generated by detection tools—and those false positives were then used rhetorically to dismiss real documentation.

This dynamic is particularly insidious: people with no propaganda agenda can run real images through faulty detection tools, get false positives, and then circulate claims of fakery in good faith. The inverse deepfake effect doesn’t require coordinated disinformation—it can emerge from well-intentioned skepticism combined with unreliable verification infrastructure.

Electoral Politics

The “AI Alibi” in American Politics

An AP report from September 2025 explicitly framed “blaming AI” as an emerging political tactic—a successor to “fake news” as a denial strategy. The piece documented how political figures have dismissed embarrassing or incriminating content as “probably AI,” even when their own teams indicated the content was authentic.

This represents the liar’s dividend in action: once “AI” becomes a culturally legible explanation, it can be deployed strategically to stall accountability.

Deepfake Robocalls as Election Interference

On the fabrication side, the FCC ruled in February 2024 that AI-generated voices in robocalls fall under “artificial” voice restrictions, following the Biden voice-clone robocalls in New Hampshire.

In May 2024, an eventual $6 million fine by the FCC signaled that election-related deepfakes would face enforcement.

But the inverse dynamic also appeared: legitimate campaign content and authentic political statements have increasingly been met with reflexive claims of AI manipulation, particularly on social media, making it harder for voters to know what’s real.

Politicians Claiming Deepfakes

Australia: David Speirs

ABC News reported in September 2024 on a case involving former South Australian Liberal leader David Speirs, who reportedly described a damaging video as a “deepfake” in denying wrongdoing. This case illustrates how “deepfake” has become an immediately available defensive frame for politicians facing video evidence.

Speirs later admitted the deepfake defense was false and plead guilty to supplying cocaine to two men.

India: Politicians Dismiss Leaked Audio as “AI Fabricated”

Rest of World documented a case in 2023 where an Indian politician claimed that leaked audio clips were “AI deepfakes.” The outlet had experts test the audio: one clip was assessed as likely authentic, another showed signs of possible tampering. The case demonstrates how “AI fabricated” functions as a ready-made shield amid controversy—regardless of whether the claim is true.

Corporate and Personal Contexts

Executive Impersonation Fraud

Beyond Arup, the Financial Times reported in May 2024 that WPP’s CEO was targeted by an attempted scam using voice cloning and a fake meeting setup designed to extract money or sensitive data. These cases represent the fabrication side of the deepfake problem—sophisticated impersonation for financial gain.

Personal Sabotage via Synthetic Audio

The Associated Press reported in April 2025 on the outcome of a Maryland case where a racially Black school athletic director (Dazhon Darien) used AI to generate a racist and antisemitic audio recording impersonating a racially White principal (Eric Eiswert).

The fabrication caused real-world disruption before being identified as synthetic. The athletic director was eventually sentenced to 4 months in jail.

When the Inverse Effect Isn’t Strategic—Institutional Misfires

Perhaps the most revealing case for understanding the inverse deepfake effect involves no strategic denial at all. It’s simply an institution—and a community—reaching for “deepfake” as an explanation when no deepfake existed.

The Guardian reported in May 2024 on the Pennsylvania cheerleading case: a woman was accused of creating “deepfake” incriminating videos of teenage cheerleaders.

She was arrested, publicly vilified, and treated as a deepfake mastermind—only for it to later emerge that nothing was fake. The videos were 100% authentic.

This case matters because it shows the inverse deepfake effect at its most corrosive: “deepfake” has become such a culturally available explanation that it can be applied incorrectly, accelerating into a social fact before anyone actually verifies whether synthetic manipulation occurred.

The Archetypes: Who Is Vulnerable to What?

The inverse deepfake effect creates a new vulnerability landscape. I don’t think society splits neatly into “gullible” vs. “skeptical.” Instead, people cluster into different error profiles based on which mistake they’re more likely to make:

False acceptance: Believing something fake is real.

False rejection: Dismissing something real as fake.

Archetype 1: The Perma-Gullible

High false acceptance, low false rejection.

This person:

Trusts video and audio as inherently credible

Responds strongly to vivid, emotional media

Overestimates their ability to detect fakes

They’re vulnerable to deepfake scams, impersonation fraud, and “attack media” designed to inflame or deceive. The iScience research on overconfidence described exactly why confidence can be high even when detection accuracy is poor.

Archetype 2: The Perma-Skeptic

Low false acceptance, high false rejection.

This person:

Defaults to cynicism: “everything is staged/AI/edited”

Uses “deepfake” as a general-purpose rebuttal for inconvenient evidence

Resists updating beliefs even when authenticity is verified

They may be hard to scam with a deepfake, but they’re easy to manipulate with denial—especially if the evidence threatens their worldview.

This is what the liar’s dividend runs on: you don’t need to prove a clip is fake; you just need a large, ready-made audience that treats “could be AI” as decisive.

Archetype 3: The Motivated Toggler

Selective reality based on identity and allegiance.

This is the most politically consequential profile:

If the clip harms “my side”: “AI / deepfake / staged.”

If it harms “the other side”: “obviously real.”

A 2025 American Political Science Review study on the liar’s dividend provides experimental evidence that politicians can gain support by claiming scandals are fake—often by introducing uncertainty and giving supporters a rationale to discount damaging information.

This archetype makes the inverse deepfake effect politically operational: denial doesn’t need to convince everyone, just enough of the right audience to blunt accountability.

Archetype 4: The Outsourced Believer

Trust-by-delegation.

This person:

Doesn’t evaluate media directly

Relies on a small set of trusted institutions or influencers as authenticity gatekeepers

Accepts or rejects based on who endorses the content

This can be resilient—if gatekeepers are rigorous. It’s catastrophic if gatekeepers are wrong, captured, or simply outpaced by the content cycle.

Archetype 5: The Careful Verifier

Low false acceptance AND low false rejection.

This person:

Doesn’t try to “spot fakes” by vibes

Uses proof-of-origin (provenance), corroboration, and source evaluation

Treats “unverified” as its own state—not automatically “true” or “fake”

This is the posture courts and serious newsrooms aspire to. But it’s cognitively expensive and requires friction that most people don’t have time for in daily media consumption.

Inverse Deepfake Effect Implications

The inverse deepfake effect carries distinct implications across different domains. Here’s my assessment of severity, from most to least consequential:

1. Erosion of Democratic Accountability (Highest Impact)

If elected officials and powerful institutions can dismiss authentic evidence of wrongdoing by gesturing toward “AI,” the entire accountability mechanism of democratic society degrades. This is the liar’s dividend at its most corrosive: scandals become harder to adjudicate, oversight becomes easier to delegitimize, and political actors face reduced costs for misconduct.

The AP reporting on “AI alibi” as political tactic documents this trajectory in real time.

2. War Crimes Documentation Becomes Contested

In conflict zones, the inverse deepfake effect can undermine the documentation of atrocities. When real footage can be dismissed as “AI” based on faulty detectors or bad-faith claims, justice becomes harder to pursue and perpetrators gain plausible deniability.

The Israel-Gaza detector false positives and VOA reporting on Bucha denial narratives illustrate how this plays out in practice.

3. Legal System Authentication Crises

The “deepfake defense” has already entered courtrooms. The ABA’s Judges’ Journal describes the evidentiary tangle: litigants can now argue that video evidence can’t be trusted because it “might be fake,” complicating authentication standards.

A 2025 University of Colorado Boulder “Visual Evidence Lab report” called for legal reforms to address the growing trend of attorneys and defendants challenging real footage by claiming synthetic manipulation.

4. Journalism and Verification Overload

News organizations face escalating pressure to verify content authenticity—but verification is expensive and slow, while claims of fakery are cheap and fast. This asymmetry advantages denial.

The Washington Post’s Content Credentials test shows how fragile proof-of-origin (provenance) infrastructure remains at the platform layer, even when authenticity markers exist at creation.

5. Institutional Misfires and Reputational Destruction

As the cheerleading case demonstrates, the inverse deepfake effect can destroy innocent people when institutions or communities prematurely reach for “deepfake” as an explanation. The social acceleration can be devastating long before facts are verified.

6. Corporate Fraud and Impersonation

While the Arup and WPP cases represent the fabrication side (deepfakes as attack), the inverse effect also applies: legitimate communications and verification requests may be dismissed as potential scams, creating operational friction.

7. Interpersonal Trust and Personal Relationships

At the individual level, the inverse deepfake effect can make it harder to trust intimate or personal media. This has implications for everything from relationship disputes to family communications.

Did anyone predict the inverse deepfake effect?

What Was Clearly Anticipated

The strategic liar’s dividend was explicitly predicted:

Chesney and Citron’s California Law Review article (2019) warned that deepfakes would make authentic evidence easier to dismiss.

A CFR report cautioned that awareness campaigns could be double-edged: skepticism can protect against fakes but can also be exploited for denial.

The Guardian discussed the “liar’s dividend” as early as July 2018 in the context of emerging deepfake capabilities.

So: analysts modeled the alibi. They anticipated that wrongdoers would claim real evidence is fake.

What Was Underappreciated

What feels newer—and what I’m specifically focused on—is how quickly the inverse deepfake effect became an everyday cognitive posture, independent of strategic manipulation:

Mass false rejection: Real events are routinely met with “probably AI” even absent an organized denial campaign.

Tool-driven mislabeling: Low-quality AI detectors and compression artifacts are generating false positives that get weaponized as evidence of fakery.

Institutional misfires: Authorities and communities are reaching for “deepfake” as a default explanation and causing harm before facts settle.

Proof-of-origin collapse at distribution: Even when authenticity markers exist, platforms strip or fail to surface them, making “closure” socially difficult.

The analysts predicted the alibi. They did not fully predict how quickly the public would internalize the alibi as a default worldview.

The Double-Edged “Immunity”

An immunity metaphor is directionally correct: awareness of deepfakes has made the public less naively trusting of video and audio evidence.

The protective side: A population that doesn’t automatically believe every shocking clip is less vulnerable to a single forged video causing mass panic. Ukraine’s early experience with the Zelensky surrender deepfake is often cited as a case where rapid debunking and public awareness reduced impact.

The corrosive side: If nothing can “close” a dispute—if evidence can always be dismissed with “maybe it’s AI”—then accountability collapses. The entire evidentiary foundation of journalism, courts, and democratic oversight weakens.

This is why I frame it as immunity that can become autoimmune disease: the antibodies can overshoot and attack healthy tissue.

The Trajectory: Where This Goes as AI Improves

I don’t expect a clean victory for “deepfakes” or for “skepticism.” Both will increase, and the battleground will shift.

Phase 1: Visual “Tells” Degrade

We’re already past the era where “look at the hands” or “check for weird mouth movements” reliably identifies deepfakes. Generation quality is improving faster than human detection ability.

Phase 2: The Shift to Proof of Origin (Provenance)

The future of authenticity verification is less about detecting fakes and more about proving origins. C2PA’s Content Credentials specifications represent this direction: cryptographically signed provenance records that certify where content came from and what happened to it.

Even perfect provenance doesn’t automatically make a claim true — it mainly answers where the media came from and how it was edited; it can’t by itself prevent miscaptioning or out-of-context reuse.

The Washington Post test is the warning: provenance can exist at creation and vanish at distribution.

Phase 3: Verification Becomes Social Again

If technical provenance remains fragile, people will revert to trust networks: “I believe it because I trust the outlet/person.” This can work—but it also risks fragmenting reality along identity lines.

Phase 4: High-Stakes Verification Goes Offline

For sensitive decisions (business approvals, political orders, crisis response), organizations will increasingly adopt out-of-band verification:

Callbacks to known numbers

Multi-person approvals across separate channels

Code words and shared secrets

In-person confirmation for critical instructions

This represents a partial retreat from the assumption that digital communication can be self-authenticating.

Defenses Against the Inverse Deepfake Effect

If the inverse deepfake effect is real and consequential, what actually helps?

1. Make “That’s AI” an Evidentiary Claim, Not a Conversation-Stopper

“AI” shouldn’t function as a magic word that ends accountability.

If someone asserts “that’s AI” / “that’s a deepfake,” they should be expected to provide specific, checkable reasons — not vibes.

Examples of what counts as evidence:

A broken provenance trail (or none exists when it reasonably should)

Conflicts with independent reporting, timestamps, or on-the-ground corroboration

A repeatable forensic explanation (not “my friend ran a detector”)

Integrity anomalies in the original file (not a re-encoded repost)

Norm to push: “Claiming fake requires receipts.” Otherwise “deepfake” becomes a cheap rhetorical veto.

2. Shift From “Spotting Fakes” to Proving Origin and Integrity

Detection-by-tells is a declining strategy. The winning move is to make authenticity cheap to prove.

The core target is a proof bundle that answers:

Where did this file originate?

Has it been edited, and how?

Has it been re-encoded, cropped, or stripped of signals?

Do independent sources match the same event/time?

This can be implemented as:

Signed origin manifests (creator-side)

Hash commitments (publish the fingerprint early; reveal originals later if needed)

Chain-of-custody logs (who handled the file and when)

Third-party attestation (newsroom/NGO/legal escrow can vouch without full public disclosure)

Key point: provenance doesn’t prove “the claim” is true — it proves the file’s story is coherent.

3. Build Privacy-Preserving Authenticity (So “Proof” Doesn’t Become Doxxing)

“Preserve everything” can turn into a doxxing machine.

So the design goal is selective disclosure:

Strip sensitive metadata by default (precise location, device identifiers)

Allow pseudonymous signing (keys that build reputation without revealing identity)

Permit redaction while maintaining integrity (prove “something was redacted” without exposing what)

Avoid “authenticity tags” that become persistent tracking beacons across platforms

Use escrow models for high-risk sources: a trusted verifier can hold the full original while the public sees a proof-of-integrity summary

This keeps the system usable for at-risk sources who cannot safely publish raw origin data.

4. Platform-Native Verification: Provenance + AI Odds + Human Notes

Platforms shouldn’t “declare truth.” They should surface structured uncertainty and evidence.

Layer A — Provenance surfacing

Preserve content credentials if present

Display them prominently (not buried)

Show what’s missing (e.g., “no origin record” is itself a signal)

Layer B — AI-assisted analysis (odds, not certainty)

A useful system provides:

A probability + confidence band

The basis for the score (what signals were used)

Clear limits (what the tool cannot infer)

Hard requirement: calibration. If it says “70% likely synthetic,” that should mean something over many cases — otherwise it becomes just another rumor engine.

Also: no automatic takedowns based solely on model output. Detector results should be treated as advisory, not dispositive.

Layer C — Human Community Notes for disputed / viral items

Do what works: evidence-linked notes, with cross-perspective gating.

“Unverified / source unknown”

“Real media, false claim”

“Old clip re-used”

“Original located / corroborated by X”

“Key context missing”

Guardrails:

Notes require links to primary evidence

Appeals and competing notes are allowed

No real-name requirement

“Unverified” is a legitimate final state when certainty isn’t available

5. Normalize “Unverified” as a First-Class Outcome

Right now the internet forces binary thinking: real vs fake.

You want a third state that people can accept without losing face:

Verified

Unverified

Deceptive / altered

This matters because the inverse deepfake effect thrives on unresolved ambiguity. If “unverified” becomes socially acceptable, people stop reaching for “AI” as the default rhetorical escape hatch.

Platform UX can reinforce this:

Friction before sharing disputed media

Visible “verification status” labels

Downranking “unknown origin” content without pretending to adjudicate it

6. Fast, Evidence-First Response Playbooks (So Doubt Doesn’t Fossilize)

When something goes viral and contested, speed matters — not to “decide truth,” but to publish the best available evidence bundle early.

A good response bundle includes:

The highest-quality available originals (when safe)

A timeline (what happened when, what’s confirmed vs unknown)

Corroboration links (independent sources, geolocation, witnesses)

A changelog (what was updated and why)

This prevents the common failure mode where uncertainty lingers long enough to become permanent cynicism.

7. High-Stakes Actions: Assume Communications Are Not Self-Authenticating

For business approvals, political orders, financial transfers, and crisis response, treat audio/video as non-authoritative by default.

Standard hygiene:

Callbacks to known numbers (not numbers provided in the message)

Multi-person approvals across separate channels

Challenge-response phrases (shared secrets that rotate)

In-person confirmation for the most sensitive actions

This doesn’t “solve deepfakes” but it does make them a bit more operationally expensive.

How Serious Is This Compared to Deepfakes?

To be clear: I’m not arguing the inverse deepfake effect is “more important” than deepfakes themselves. They are two sides of the same synthetic-media problem:

Deepfakes increase false acceptance: fake events accepted as real.

The inverse deepfake effect increases false rejection: real events rejected as fake.

Both are serious and scale.

And the dangerous part is their interaction: more convincing fakes make denials more plausible, and louder denials raise baseline confusion—making future fakes easier to land.

If forced to identify which causes more systemic damage, I’d note that deepfakes cause acute, identifiable harms (fraud, harassment, sabotage), while the inverse deepfake effect causes chronic, diffuse harm (erosion of evidentiary authority, degraded accountability, fractured shared reality).

Conclusion

Deepfakes threaten reality by fabricating events. The inverse deepfake effect threatens reality by making real events deniable.

The strategic version of this—the liar’s dividend—was anticipated by early deepfake researchers. What’s exceeded expectations is how quickly the inverse deepfake effect has become an ambient psychological posture: ordinary people, institutions, and even automated tools are now generating false rejections of authentic media at scale.

Unless provenance infrastructure becomes durable at the platform layer—and unless “that’s AI” starts requiring actual evidence—I expect both dynamics to intensify.

The future won’t be decided by who can generate the most realistic fake. It will be decided by who can implement systems/tools (likely involving rapid AI deepfake analysis) where authenticity can be proven cheaply, quickly, and publicly.