Gray Goo to Green Goo: Weaponized Nanobots and Existential Risk

When will weaponized nanobots pose an existential threat?

Keep a liter of vodka inside my locker. Use it like a book on the Grey Goose / Grey Goo scenario. Play you like a stereo. Hey you, where he go? — Viktor Vaughn

The convergence of molecular nanotechnology, synthetic biology, and nuclear physics presents a complex matrix of existential risks that will define the strategic landscape of this century. This analysis cuts through the science fiction to examine what the physics actually permits—and forbids—when it comes to self-replicating machines, weaponization, and the strange connection between nanotechnology and the origin of life itself.

The bottom line: the classical “Gray Goo” scenario (runaway ecophagy) is thermodynamically constrained in ways that make rapid global consumption implausible. But “Green Goo” (engineered biological replicators) and “Khaki Goo” (military nanoweapons) present immediate, empirically grounded risks due to rapid advancements in synthetic biology and government-funded programs like DARPA’s Living Foundries.

The Taxonomy of Catastrophe: What the Colors Mean

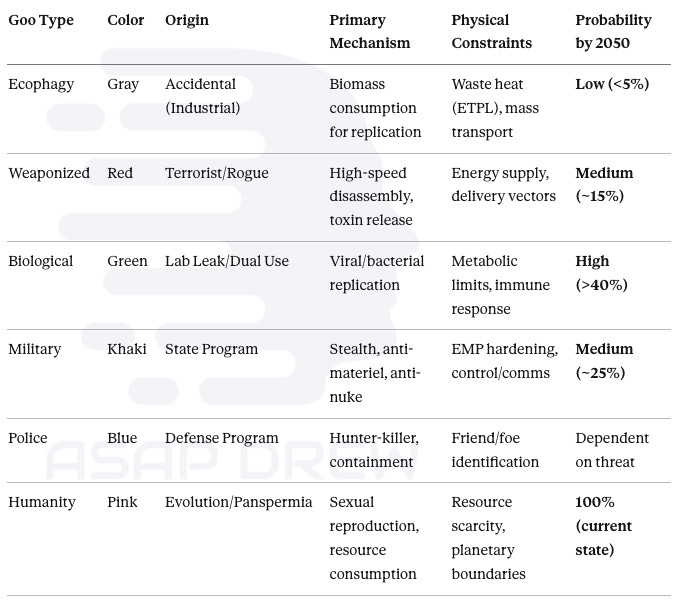

The terminology surrounding nanotechnological catastrophe has evolved from K. Eric Drexler’s original 1986 thought experiment into a color-coded taxonomy.

Each “color” represents a distinct failure mode, governed by specific physical laws and strategic intents.

Gray Goo is the foundational catastrophic scenario. Coined in Engines of Creation, it describes self-replicating nanomachines escaping containment and consuming the biosphere to produce copies of themselves—technically termed global ecophagy. The premise relies on the assembler—a nanoscale device capable of manipulating matter with atomic precision. If such a device could self-replicate using naturally occurring carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen, and lacked programmed inhibition, it could theoretically convert biomass into “nanomass” exponentially.

Drexler illustrated this with a thought experiment: a replicator copying itself every 1,000 seconds yields 2^68 replicators in less than a day—theoretically exceeding Earth’s mass within days, barring resource and thermal limits.

However, this scenario is often misunderstood. Later analysis by Drexler and Robert Freitas suggests efficient manufacturing systems would be “autoproductive” rather than self-replicating in the wild. An autoproductive system acts like a factory line: it can build a copy of itself, but only with specific, pre-refined industrial feedstocks.

Such a machine is “auxilioproductive”—it requires assistance to reproduce and cannot survive in the wild biosphere. The accidental Gray Goo is therefore less likely than the deliberate creation of a “survivor” replicator designed to forage for natural resources. This is a critical point: Gray Goo requires deliberate design choices that make it less efficient than conventional manufacturing. The thermodynamic constraints essentially rule out the “runaway accident” narrative.

Red Goo refers to nanomachines designed explicitly for destruction. Unlike Gray Goo, which destroys as a byproduct of replication, Red Goo is weaponized—a doomsday technology prioritizing speed of disassembly and resistance to countermeasures over efficient replication. It’s the technological analogue to a nuclear first strike.

Green Goo represents the intersection of nanotechnology and synthetic biology—out-of-control biologicals or bionanotech devices. Unlike the “dry,” diamondoid machinery of Gray Goo, Green Goo would be wet, enzymatic, and DNA/RNA-based. Given that bacteria are already self-replicating nanomachines that consume biomass, Green Goo is the most empirically plausible scenario. It implies an engineered organism—perhaps designed for plastic degradation or biofuel production—that outcompetes natural flora and fauna, sterilizing the biosphere or altering atmospheric composition.

Golden Goo stems from the “Wizard’s Apprentice” problem: nanomachines programmed to filter economically valuable substances (gold from seawater) replicate uncontrollably to maximize yield. The resource consumption required to filter trace elements from the global ocean could lead to ecological collapse. This highlights the danger of utility function optimization in autonomous systems—a machine maximizing gold production does not value the plankton it destroys.

Black Goo and Khaki Goo represent stealth/psychological warfare and military applications respectively. Khaki Goo is the result of a state-level “Manhattan Project” for nanotechnology—replicators hardened against EMPs, radiation, and defensive countermeasures. It represents the strategic equilibrium of a nanotech-enabled world, where nations maintain stockpiles of replicators as deterrents.

Pink Goo is largely philosophical: it describes human beings. We are, by definition, self-replicating, biomass-consuming machines governed by molecular programming. The biosphere is already a “goo” scenario that has reached competitive equilibrium. The danger of artificial goo is introducing an invasive species with a metabolic advantage into this balanced system.

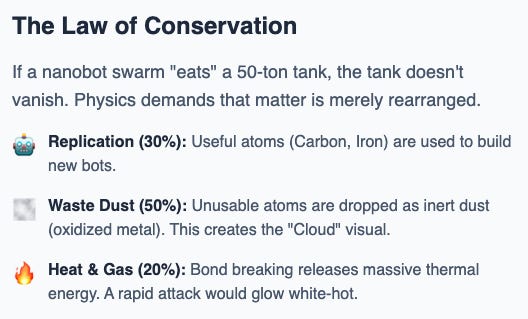

How Nanobots Actually “Consume” Matter

The word “eating” is misleading. Nanobots don’t have stomachs—they perform disassembly. Think of a Lego castle (the target) and a Lego robot (the nanobot):

The bot uses chemical or mechanical arms to grip a molecule, applies energy or a catalyst to break atomic bonds, then sorts the atoms. “This is carbon (useful for replication). This is calcium (waste).”

Physics demands conservation of mass: if a swarm “eats” a 50-ton tank, that 50 tons doesn’t disappear. It becomes new bots (replication feedstock), waste dust (atoms the bot can’t use, dropped behind it), and gas/heat from exothermic reactions.

If carbon-based bots consumed a human body, they’d strip the carbon and leave piles of calcium, phosphorus, and other elemental dust. If a nanobot swarm ate a car, the car wouldn’t vanish—it would transform into a cloud of new bots, metallic dust waste, and a wave of heat. The “Gray Goo” isn’t the bots themselves; it’s this residue of unusable atoms accumulating as the swarm moves through matter.

Why the World Won’t Melt Instantly: The Thermodynamics of Ecophagy

The most significant barrier to any Goo scenario is not programming, but physics—specifically, thermodynamics. Robert Freitas produced the definitive quantitative analysis in “Some Limits to Global Ecophagy by Biovorous Nanoreplicators.”

Self-replication is an irreversible process that generates entropy. Breaking chemical bonds in biomass to reassemble them into nanorobots releases energy. Freitas calculated that if nanorobots are constructed of diamondoid materials (carbon-rich), the conversion of biological carbon into diamondoid structure is exothermic.

If ecophagy proceeds too rapidly, the waste heat generated would raise the global temperature to lethal levels long before biomass was fully consumed. This is the Ecophagic Thermal Pollution Limit (ETPL).

The numbers: if the replication process dissipates 100 MJ/kg (conservative for chemical transformations), and the goo attempts rapid consumption, the thermal signature would be blindingly obvious to satellite monitoring. Freitas estimates that an ecophagy event slow enough to only add ~4°C to global warming (the threshold for immediate climatological detection) would require approximately 20 months to run to completion. Faster replication boils the environment, likely destroying the replicators themselves or denying them the liquid water required for mobility and chemistry.

Replicators must also move to find food. As the goo converts the local environment, it creates a “desert” of waste heat and inert byproducts. The frontier must physically move to new unconsumed biomass. This expansion velocity is limited by viscosity and drag (nanobots face significant drag in air or water), resource scarcity (a carbon-based replicator is strictly limited by carbon-rich biomass availability—air is mostly nitrogen/oxygen, soil is mostly silicon/oxygen), and atomic inventory (a human body is ~23% carbon by weight; to build a diamondoid robot at nearly 100% carbon, the replicator must discard the vast majority of feedstock, creating a massive waste disposal problem).

The verdict: While the programming for Gray Goo is theoretically possible, the physics imposes a speed limit. A “lightning-fast” consumption of Earth is thermodynamically impossible; a “slow burn” (months to years) is possible but allows time for detection and countermeasure deployment.

Can Nanobots “Eat” Nuclear Weapons? The Physics of Disarmament

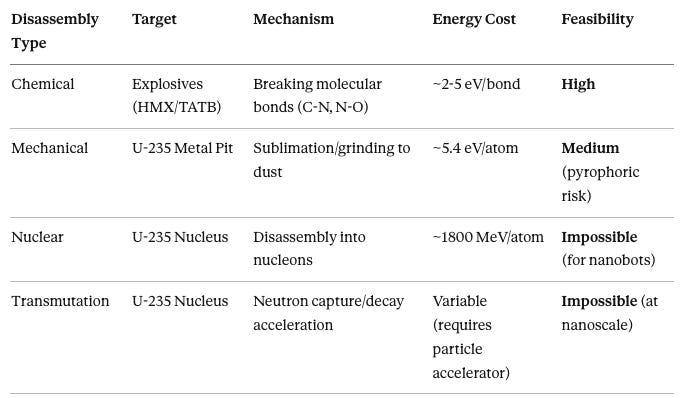

The concept of nanobots eating nuclear weapons requires rigorous deconstruction. One must distinguish between chemical disassembly (neutralizing high explosives and electronics) and nuclear transmutation (changing fissile uranium/plutonium into harmless elements). The former is engineering; the latter confronts fundamental energy scales.

A modern thermonuclear weapon like the W88 warhead contains: the fissile core (pit) of Plutonium-239 or highly enriched Uranium-235; the tamper/reflector of U-238 or Beryllium; high explosive lenses (HMX or TATB) arranged for symmetrical implosion; and triggering electronics with high-voltage capacitors and krytron switches.

Chemical Disassembly: High Feasibility. Nanobots could chemically degrade the high explosive lenses by breaking nitrogen-carbon bonds in HMX, reducing the explosive to non-volatile sludge. Without precise geometry, symmetrical implosion becomes impossible, and nuclear chain reaction cannot initiate. Nanobots could also sever microscopic wires of firing circuits or corrode krytron switches—no exotic physics required, merely manipulation of copper, gold, and silicon at micron scale.

The energy requirement: Breaking a chemical bond costs ~2-5 electron-volts per bond (~10^-19 Joules). This is well within operational capacity of chemical or solar-powered nanobots.

The risk: If explosives degrade unevenly, a partial detonation or “fizzle” could occur—not producing nuclear yield but scattering radioactive material, effectively creating a dirty bomb.

Nuclear Transmutation: The Thermodynamic Wall. “Eating” the nuclear weapon implies consuming the fissile core. This moves from chemistry (electron orbitals) to nuclear physics (the nucleus), where energy scales increase by a factor of one million.

The nucleus of Uranium-235 is held together by the strong nuclear force with binding energy of approximately 7.6 MeV per nucleon. Disassembling one U-235 atom requires roughly 1800 MeV (~10^-10 Joules). Chemical disassembly requires ~4 eV per atom. Nuclear disassembly is therefore ~450 million times more energy-intensive than chemical disassembly.

A nanobot cannot “eat” a uranium atom in the sense of breaking it down. Nanobots operate using chemical energy; they lack the gigaelectron-volt power sources required to manipulate nuclear binding forces.

Could nanobots turn uranium into lead? Transmutation requires changing proton count via neutron bombardment or high-energy particle collision. The only energetically favorable way to “destroy” U-235 is to fission it—which releases ~200 MeV per atom as massive radiation and heat, instantly vaporizing the nanobot swarm. Electronic and diamondoid components are highly susceptible to radiation damage; neutron flux from a reacting core would degrade control systems long before effecting significant change.

Mechanical Separation: Plausible but Hazardous. A third option: nanobots could grind the U-235 pit into dust and scatter it, preventing criticality by geometry. The energy to separate uranium atoms (sublimation/atomization) is governed by metallic lattice binding energy of roughly 5.4 eV per atom.

To atomize a 10kg pit: ~42.5 moles of uranium yields ~2.56 × 10^25 atoms, requiring ~21.6 MJ total (equivalent to ~5 kg TNT). A swarm could theoretically grind the core to dust. However, uranium metal is pyrophoric—it ignites spontaneously when powdered. The resulting uranium fire would be a thermal beacon alerting defenders and likely destroying the swarm.

Chemical disassembly targets conventional explosives like HMX and TATB by breaking molecular bonds at 2-5 electron-volts per bond—highly feasible for nanobots.

Mechanical disassembly involves grinding the uranium-235 metal pit to dust via sublimation at 5.4 eV per atom—technically possible but carries severe pyrophoric risks.

Nuclear disassembly would require overcoming binding energies of approximately 1800 MeV per uranium atom to break down nuclei into constituent nucleons—impossible for chemical-energy-powered nanobots.

Transmutation to convert U-235 into stable elements requires particle accelerator energies—completely impossible at nanoscale.

The verdict: Nanobots “eating” nuclear weapons is physically feasible only as chemical neutralization of trigger mechanisms. It is thermodynamically impossible as nuclear disassembly. The most likely outcome of a nanotech attack on a stockpile: conversion of functional warheads into inert, radioactive sludge.

Manufacturing Paradigms: How We Actually Build These Things

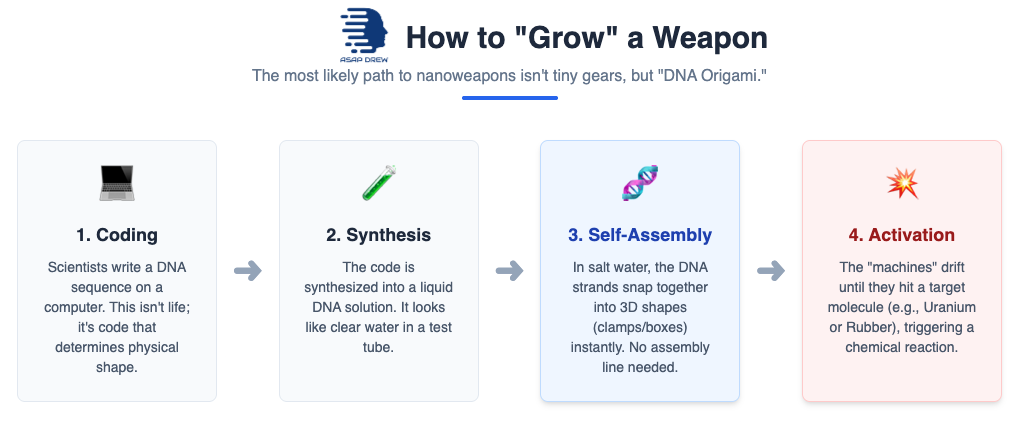

The capability to build such nanobots depends entirely on the manufacturing paradigm. The debate bifurcates into “Dry” (mechanosynthesis) and “Wet” (biological) approaches.

Top-Down: The Limits of Silicon. This approach extends semiconductor manufacturing to the nanoscale—carving structures from bulk silicon using photolithography or electron beams. Current lithography reaches ~7nm feature sizes but struggles to create complex 3D moving parts with atomic precision. It’s inherently 2D (layer-by-layer), producing MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) that are microns in size—too large to manipulate individual molecules effectively.

Nobel Laureate Richard Smalley argued the “fat fingers” problem: manipulators used to build nanobots must be made of atoms and thus cannot be smaller than the atoms they’re manipulating.

Bottom-Up: Bio-Nanotech and DNA Origami. The “wet” approach uses existing machinery of life—DNA, RNA, and proteins—as building materials. DNA Origami uses base-pairing rules (A pairs with T, C with G) to fold long strands into precise 3D shapes acting as scaffolds, drug cages, or simple logic gates.

This solves the fat fingers problem by using chemistry’s “sticky fingers.” Mix chemicals in a test tube; they self-assemble based on thermodynamic properties.

Current progress: The Wyss Institute has developed “molecular robotics” using DNA for drug delivery and sensing. DARPA’s Living Foundries aims to create programmable manufacturing platforms using biology, successfully producing over 1,600 unique molecules and materials not found in nature. Notably, DARPA continues aggressive investment in synthetic biology with AI integration as of early 2026, accelerating capabilities beyond earlier projections.

Strategic implication: This path leads to Green Goo. Because it uses biological substrates, it’s compatible with the biosphere. A runaway DNA-based replicator acts essentially as a synthetic virus—the most immediate and plausible vector for a self-replicating threat.

The “Dry” Dream: Diamondoid Mechanosynthesis. This is Drexler’s original vision: stiff, diamond-like structures built atom-by-atom using mechanosynthesis—a probe tip (like an Atomic Force Microscope) mechanically placing atoms into lattice structures. While scientists have moved individual atoms (IBM’s xenon atoms), building complex machines this way at scale remains unsolved. The Foresight Institute Technology Roadmap outlines the path, but diamondoid manufacturing remains decades away.

The Smalley-Drexler debate: Smalley argued “sticky fingers” (atoms sticking to manipulator arms) would prevent mechanosynthesis. Drexler argued stiff machine-phase systems would overcome this using forces stronger than van der Waals. Current evidence suggests both are partially right: manipulation is possible, but mass production requires massive parallelization (millions of tips working in concert).

The theoretical feasibility debate has largely settled in favor of molecular nanotechnology being physically possible. The focus has shifted to timelines and safety.

The gap between current capabilities—plastic-eating bacteria for battlefield logistics, bacterial coatings protecting naval vessels from corrosion—and weaponized applications is engineering, not physics. The chassis exists. The weaponization pathway is clear.

Panspermia and the “Alien Goo” Hypothesis

The discussion of self-replicating nanomachines inevitably intersects with the origin of life. Life is a self-replicating nanotechnological system, and its sudden appearance on Earth has led to hypotheses mirroring modern nanotechnology concepts.

In 1973, Francis Crick (co-discoverer of the DNA double helix) and Leslie Orgel proposed Directed Panspermia. They argued the complexity of life and universality of the genetic code might suggest intentional origin rather than random chemical evolution.

The universality argument: The genetic code is nearly identical across all terrestrial life. If life had evolved randomly in multiple locations on early Earth, one might expect different coding systems. The universality suggests a single “infection” event by a specific biological template.

The molybdenum argument: Crick and Orgel noted certain enzymes crucial to life depend on molybdenum, rare on Earth. They hypothesized life might have evolved where molybdenum was abundant before being transported here. (Later geological studies suggest molybdenum may have been sufficiently available in Earth’s early oceans, weakening this specific point, but the core argument of directed seeding remains coherent.)

The scenario: An advanced civilization, perhaps facing extinction or purely for scientific seeding, sent a payload of microorganisms (”Green Goo”) to Earth ~4 billion years ago containing the biosphere’s “starter kit.”

The connection to nanotechnology is fundamental: if we develop interstellar probes, we will likely use self-replicating nanobots (von Neumann probes) to explore or seed the galaxy.

Sending a small, self-replicating seed is exponentially more efficient than sending a large colony ship. The seed lands, uses local resources to build factories, then produces exploration fleets or terraforming equipment.

The “Pink Goo” implication: if Directed Panspermia is true, humanity is essentially the result of a “biological weapon” or “terraforming agent” deployed by alien intelligence.

We are the “Pink Goo” that has consumed the biosphere (ecophagy) and is now attempting to leave the planet to replicate elsewhere (Mars colonization, Voyager probes).

This reframes the Gray Goo fear: we are afraid of creating a competitor that does to us what we did to the Neanderthals and megafauna.

Strategic Timelines and Probability of Weapons and/or Catastrophe

When do these scenarios move from theory to reality? The convergence of AI and biotech provides probabilistic timelines.

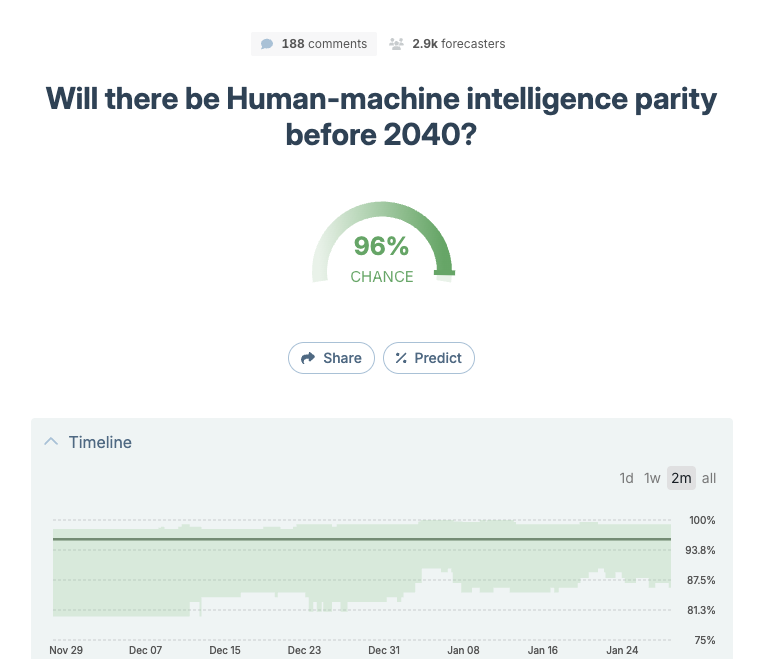

AI timeline surveys cluster median estimates for “High-Level Machine Intelligence” (which would accelerate nanotech design through generative material science) around 2040-2060, though AI progress has accelerated significantly since earlier forecasts.

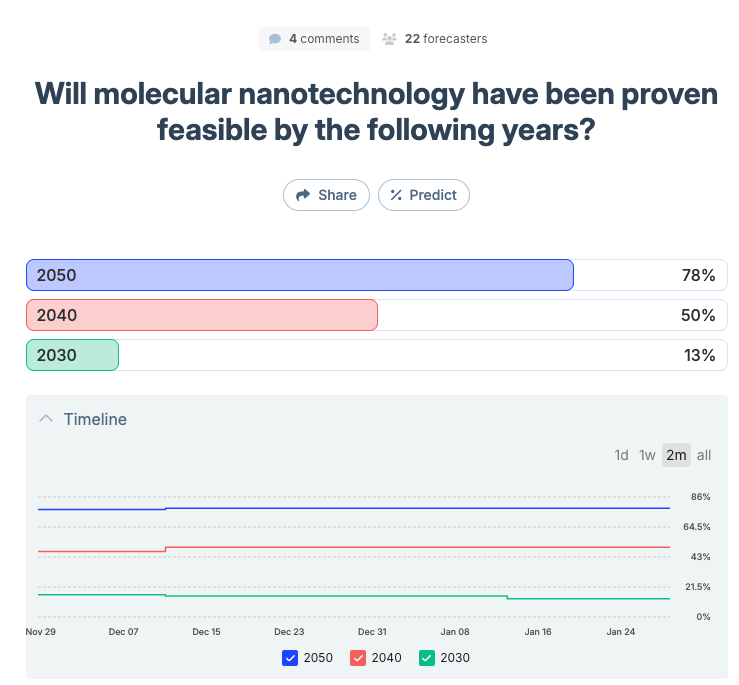

A Metaculus forecast for “Molecular Nanotechnology Proven Feasible” has resolution around 2050, with high uncertainty.

The Foresight Institute roadmaps have moved from “speculative” to “incremental,” focusing on Atomic Precision Manufacturing as gradual evolution rather than sudden breakthrough.

The weaponization timeline (Khaki Goo) will likely precede civilian “abundance” applications due to first-strike strategic advantages:

2025-2035: Maturation of Green Goo (synthetic biology) with capabilities including targeted materials, advanced sensors, and potentially binary biological weapons. DARPA’s “Living Foundries” programs are already delivering results.

2035-2045: Integration of AI with chemical synthesis (generative AI for molecules), enabling rapid design of novel toxins or chemical disassemblers bypassing traditional filters.

2050+: Possible emergence of true “dry” diamondoid nanofactories, enabling Khaki Goo stockpiles resistant to biological countermeasures and capable of physical destruction of infrastructure.

Gray Goo (accidental industrial ecophagy) carries low probability under 5% due to thermodynamic constraints on waste heat and mass transport—it requires deliberate design choices making it less efficient than conventional manufacturing.

Red Goo (terrorist/rogue weaponization) sits at medium probability around 15%, limited by energy supply requirements and delivery vector challenges.

Green Goo (biological, from lab leaks or dual-use research) represents the highest probability exceeding 40%, constrained only by metabolic limits and natural immune responses—this is the most immediate empirically-grounded threat given current synthetic biology progress without corresponding safety frameworks.

Khaki Goo (state-sponsored military applications) rates medium probability around 25%, requiring EMP hardening and robust command/control communications.

Blue Goo (defensive “police” nanobots) depends on threat emergence and faces fundamental friend-or-foe identification challenges similar to AI alignment problems.

Pink Goo (humanity itself) is at 100% probability as our current state—we are self-replicating biomass consumers already constrained by resource scarcity and planetary boundaries.

Synthetic biology reaching Green Goo maturity is estimated for the 2025-2035 window based on current DARPA Living Foundries progress and continued rapid advancement in bio-nanotechnology.

Human-level machine intelligence is projected for before ~2040 based on Metaculus community forecasts and AI Impacts expert surveys, though recent acceleration in AI capabilities may compress this timeline.

Molecular nanotechnology (dry diamondoid mechanosynthesis) feasibility is estimated for 2050 or later based on Metaculus forecasts and Foresight Institute technology roadmaps.

Active nanoshield deployment for defense is projected for 2050-2070 based on strategic necessity once offensive capabilities mature.

What a Red Goo Attack Actually Looks Like

Abstract probabilities don’t convey what weaponized nanotechnology means in practice. Here’s a realistic scenario for military deployment circa 2060-2080:

The Setup: A superpower wants to disable an enemy naval fleet without nuclear exchange. They deploy a canister of “Rust-01” nanobots—bots programmed to bond only to high-strength titanium alloys used in fighter jets and radar components.

Deployment: A drone releases the canister over the fleet. It looks like a puff of smoke or glitter settling on ship surfaces.

Hours 1-4: The bots use heat from ship engines as power. They begin rearranging the atomic structure of titanium, converting strong metal into brittle powder. They replicate using harvested metal atoms—1 becomes 2, 2 becomes 4. By hour 4, quadrillions of bots are at work.

The Visual Effect: To human observers, the ships appear to be rusting at impossible speed. The “red” in Red Goo isn’t the bots—it’s oxidized metal dust sloughing off structures.

The Climax: The enemy attempts to scramble jets. Landing gear snaps on contact. Radar dishes crumble. The fleet floats but is completely disarmed—billions of dollars of hardware converted to floating scrap without a single conventional weapon fired.

The Containment Failure: Wind shifts. The Rust-01 cloud drifts toward a nearby port city. The bots were programmed to eat “titanium alloy” but can’t distinguish military-grade metal from civilian infrastructure. Cars, bridges, and buildings begin degrading. This spillover—weaponized attack bleeding into civilian life—is the Red Goo nightmare scenario.

Why Red Goo Doesn’t Exist Yet

If the physics permits this, why hasn’t it happened? Two engineering barriers that science fiction ignores:

The Brain Problem: A nanobot is too small to carry a computer chip capable of decision-making. It can only follow simple chemical gradients—”if heat, move left.” This makes current-generation nanobots profoundly stupid. Release them and they’re more likely to float away or get stuck on surfaces than find and consume a target.

The Jamming Problem: Billions of bots in a dense cloud interfere with each other. They block each other’s radio signals (silicon bots) or chemical trails (bio-bots). Dense swarms tend to crash into themselves and clump uselessly rather than functioning as coordinated armies.

We’re at the “transistor” stage of nanotechnology. Red Goo requires the “supercomputer” stage—breakthroughs in autonomous coordination and molecular-scale computing that remain 50-100 years out.

Engineering the Kill Switch

For any weaponized nanobot to be deployable, militaries need confidence it won’t become Gray Goo. Three control mechanisms are theoretically viable:

Starvation (Lock and Key): Bots are engineered to metabolize only one specific molecule—enriched uranium, a particular rubber compound, a specific titanium alloy. Once they exhaust that molecule in the environment, they starve and degrade. They literally cannot digest anything else.

Suicide Timer: DNA-based bots can be programmed with genetic sequences that degrade after a set period—24 hours, 72 hours. The bot’s own chemistry disassembles it on schedule. It falls apart like rotting fruit.

Signal Dependence: Bots require a continuous broadcast signal (radio frequency or chemical marker) to remain active. Cut the signal, the swarm dies. This gives command authority an off-switch but creates vulnerability—enemies could jam the frequency.

The Ghost Risk: Since Method B (DNA-based) bots use genetic code, there’s a non-zero mutation probability. Bots could theoretically “learn” to metabolize new materials or lose their kill switch through random genetic drift. If that happens, they become permanent environmental pollution—a man-made disease attacking machines rather than organisms.

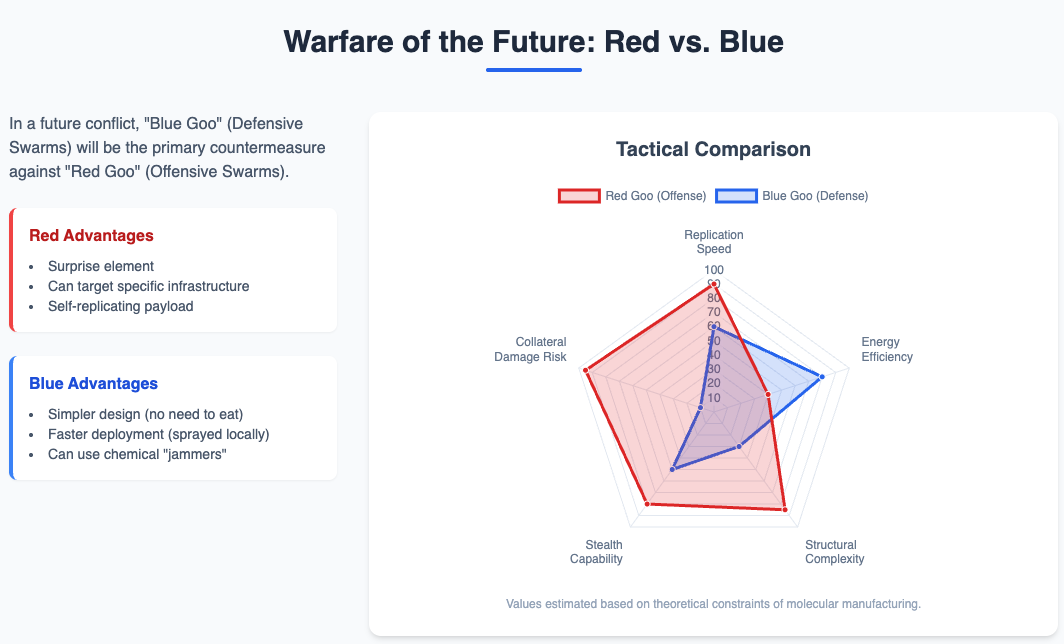

Defense and Countermeasures: The Blue Goo Strategy

If Gray Goo or Red Goo is released, how do we stop it? The defense is termed Blue Goo—benevolent nanobots designed to detect and neutralize malicious replicators.

Blue Goo would act as an “obligate parasite” on Gray Goo or a specialized hunter-killer, physically dismantling enemies or chemically gluing them together (”sticky foam” at nanoscale). Tactical advantage: Blue Goo can be designed for speed and combat, whereas Gray Goo is designed for replication and metabolism. A dedicated war-bot usually beats a general-purpose factory-bot.

Bacteriophages to hunt nanobots?

The most realistic countermeasure for DNA-based (Method B) nanobots exploits their biological nature. Since bio-bots are essentially artificial bacteria, they share bacterial vulnerabilities. Bacteriophages—viruses that naturally prey on bacteria—could be engineered to hunt specific nanobot strains.

A phage lands on the target bot, injects its own genetic payload, and causes the bot to explode from within. If a ship were attacked by corrosive bio-bots, the defense wouldn’t be lasers or EMPs—it would be spraying the hull with engineered viral agents designed to unravel the attackers’ DNA. We already use phage therapy against antibiotic-resistant infections; weaponizing it against synthetic organisms is a logical extension.

The risk: Blue Goo must be self-replicating to match exponential threat growth, creating “auto-immune disorder” risk where Blue Goo mutates or malfunctions and attacks beneficial matter. The challenge of friend-or-foe identification at nanoscale deserves emphasis—it represents a fundamental control problem similar to AI alignment.

A more robust defense is the “NanoShield“ concept paralleling biological immune systems:

Innate immunity: A layer of nanobots in atmosphere or bloodstream continuously sampling for “non-self” molecular structures. Upon detection, triggering general inflammatory response (localized heating or chemical release) to contain breach.

Adaptive immunity: Upon detecting new threats, the system uses AI to design specific counter-nanobots to neutralize the pathogen. This design broadcasts to the entire shield network.

Signal detection: Detecting waste heat or chemical signature of replicator swarms. As Freitas noted, a fast-replicating swarm generates a heat spike. Satellite-based thermal imaging could detect Gray Goo outbreak in early stages—the “fever” of the biosphere—and direct conventional weapons (thermobaric bombs, nukes) to sterilize the area before spreading.

Legislative approaches include “Inner Space Treaties”—international agreements banning self-replicating nanotech similar to the Biological Weapons Convention. However, verification is extremely difficult due to microscopic scale.

A technical safety measure is the “Broadcast Architecture” where nanobots don’t carry instruction sets onboard but receive them via broadcast. Turning off the broadcast stops the goo immediately, preventing runaway replication.

Conclusion

The Gray Goo scenario, while theoretically possible, is thermodynamically constrained. The heat generated by consuming the biosphere would likely cook the replicators before they could finish, slowing the process to a manageable timescale for human intervention. And critically, the scenario requires deliberate engineering choices that make it less efficient than conventional manufacturing—ruling out the popular “runaway accident” narrative.

However, the risk profile has shifted.

The immediate danger is not the “dry” diamondoid nanobots of 1980s futurism, but the “wet” synthetic biology of the 2020s.

Green Goo—engineered pathogens and metabolic disruptors—is being actively funded and developed under the guise of medical and industrial research.

The potential for a Green Goo event, whether accidental or weaponized, represents significant existential risk in coming decades. Current research in 2025-2026 shows continued rapid advancement in bio-nanotechnology without corresponding safety frameworks.

The notion of nanobots “eating nuclear weapons” is physically feasible only as chemical attack on weapon trigger systems, not as nuclear transmutation of the core. This capability, while valuable for disarmament, creates strategic instability by threatening the viability of nuclear deterrents.

Ultimately, the connection to Panspermia suggests that creating self-replicating machines may be a “Great Filter” or a reproductive step in the lifecycle of intelligent civilizations. Whether we are the “Pink Goo” seeding the stars or victims of our own “Gray Goo” depends on establishing robust active defenses and prudent management of the intersection between AI, biology, and physics.

We are, after all, already the most successful self-replicating nanotechnological system this planet has ever produced. The question is whether we can stay on top.