Population Genetics (DNA) Determines Corruption Levels Across & Within Countries

Aggregate population genetics explain why some countries are less corrupt than others... a byproduct of evolution & selective pressures.

I get pretty annoyed with people who continue to blame the lack of development or success or innovation in certain countries on “corruption.” Not because it’s not partly accurate, but because it’s a cop out to avoid critical thinking.

Let’s accept that “corruption” is a major issue. What causes or leads to corruption? What is the root cause of corruption? Incentives? Why do certain countries have different incentives?

Why do some countries temporarily eviscerate corruption, then it rears its ugly head again like it never left? Same shit different day, eh? Although a lot of Westerners love to embellish the idea that “there’s so much corruption in the U.S.” (or insert some other Western nation: AU, CA, EU, etc.) — the level of corruption in these countries is a drop in the bucket compared to the rest of the world.

Most people are heavily biased towards corruption in their own countries… because it’s where they live, it’s in the media/news they consume, etc. So when they hear about corruption in some faraway land, they’re like “corruption everywhere, it’s just as bad or worse in the U.S.” (or wherever they live).

Some of these people clearly have the woke mind virus and don’t want to call a spade a spade… yes some countries are cesspools of corruption far worse than the U.S. Some countries have bad “culture” and are shitty places to live (or as Trump might call them, “shithole countries”).

The reality? Most Western countries (e.g. United States, EU, UK, Canada, Australia, etc.) have INSANELY LOW CORRUPTION in both magnitude and scale relative to the rest of the world which has a LOT MORE CORRUPTION in magnitude and scale.

Burying your head in the sand and saying, “Well we have bad corruption too” is just a tactic to avoid discussing why the fuck corruption is far worse elsewhere. My hypothesis, and logical guess is that corruption is downstream of population genetics.

Aggregate population genetics → distributions of cognitive behavioral tendencies/patterns → propensity for “corruption.”

You might ask well, why is South Korea far less corrupt than North Korea? Don’t they have the same genetics?

No, they don’t. Post-WW2 and Korean War ~10-15% of North Korea’s elite/higher-IQ population fled south; North Korea implemented a hereditary caste-like system (no class mixing); family punishment for ideological crimes (imprisonment/execution); elimination/killing of independent thinkers; etc. (I could go on).

Basically the aggregate genetics of North Korea (even if “Korean”) differ significantly in meaningful ways from South Korea. Smart people were killed or executed and the fertility is dysgenic (lower IQ, autocratic social structure, etc.).

Countries like Singapore, Denmark, Finland, et al. have very low corruption because of aggregate genetic composition of the populations… longer-term thinking (realizing corruption ruins the country for future generations/kids, etc.), higher average genetic IQs, etc.

As a result? You get good leadership like the mastermind realist Lee Kuan Yew (LKY) and his “system” that transformed Singapore from a poor country to a global business juggernaut.

His system is largely maintained in Singapore by other ethnic Chinese, but if you removed the ethnic Chinese from Singapore, corruption would likely spike much higher.

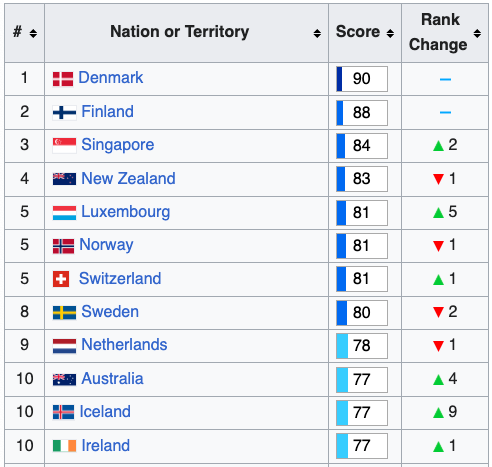

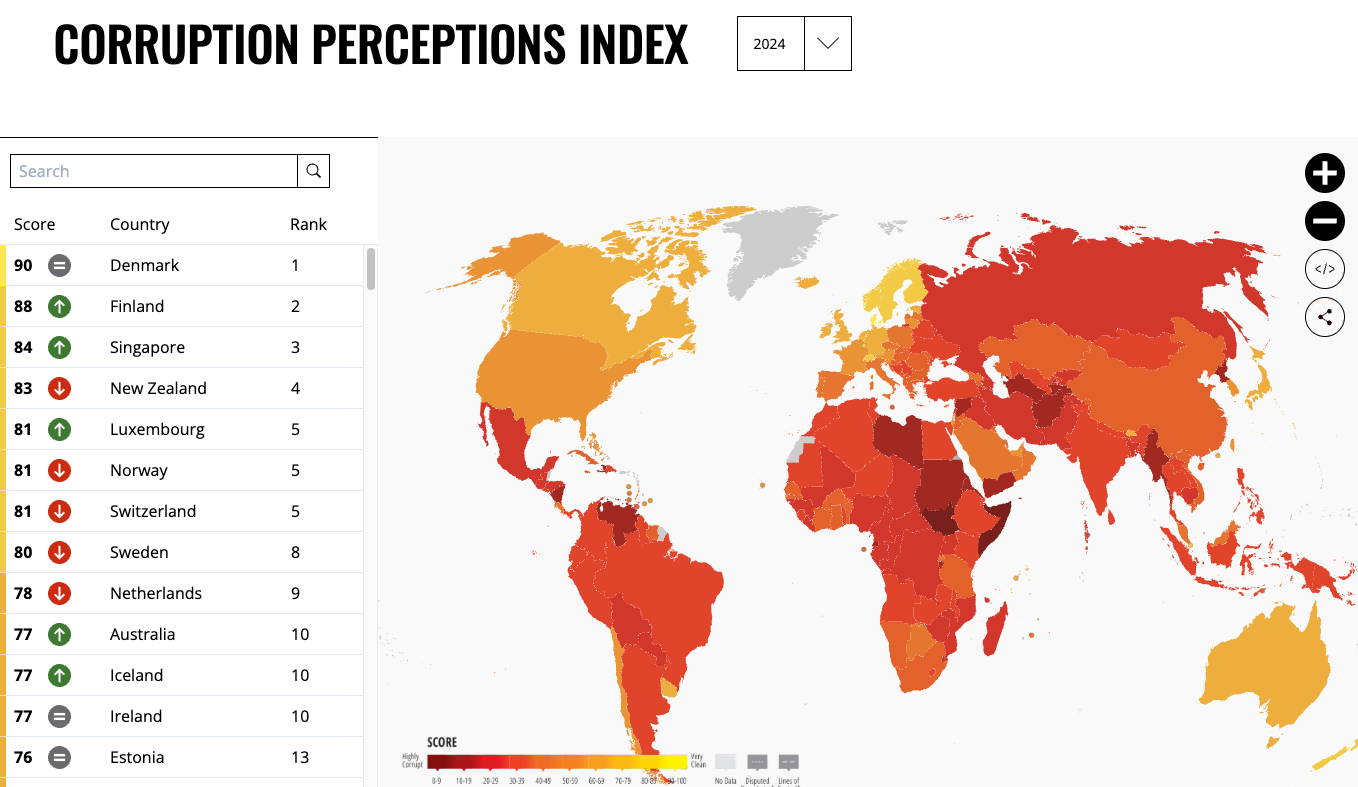

According to the “Corruptions Perception Index” for 2024 — Singapore has a score of 84 (top 3 lowest)… predictable.

Denmark is at 90 and Finland 88… both small, ethnically homogenous countries with Nordic DNA… The U.S. is ~65 but far larger and more multicultural/ diverse… so predictably, corruption is higher (more difficult to manage).

If you scroll to the bottom of the CPI for 2024, you’ll see countries with scores below 20! This means the people in these countries are mostly plotting & scheming for the present (“How can I get ahead today? I don’t care about future generations”) — with zero regard for the future of their countries (short-term thinking, impulsivity, etc.).

Years ago I read an anecdote from an African woman who wrote about an official in her country that received U.S. Aid money that was supposed to be directed towards buying food, helping people get medical treatment, education, etc.

But what actually happened with that money? It was pocketed by the official to upgrade his standard of living and get his family an elite education. Think luxury homes, luxury cars, and his kids going to Ivy League schools (e.g. Harvard) all on the dime of the U.S. taxpayer.

Now, the corruption is so bad in many of these countries that if this person had earnestly used the money in attempt to help, it’s possible somewhere downstream of his efforts — some other corrupt individual(s) would’ve stolen food or money used for the food, etc. Perhaps he decided it wasn’t even worth trying (sadly this is also the case many places… try to help and someone else just steals… so better that you steal because if you don’t someone else will.)

Once this type of system is in place, it’s difficult to uproot. You need a critical mass of non-corrupt people… but you’ll never get to this point (in my opinion) unless you address the root issue: aggregate genetics (DNA) of the population.

You need there to be significantly more people genetically oriented towards non-corruption. One way to do this is implement an instant harsh death penalty for all forms of corruption… after generations you cull the “corrupt” DNA (no longer reproducing etc. — and you get a lower corruption society.

The problem is you’d probably never reach this point with corrupt underlying genetics. And this is too alarming for the wokes of 2025. So probably would never happen… which is why many of these countries have reached an equilibrium or evolutionary steady state of “corruption.” (It may fluctuate slightly from year-to-year… but it’s not really making big leaps up/down.)

No matter how bad you think the U.S. is in corruption… other countries are Corruption Kingpins that make the U.S. look like a divine anti-corruption figurehead. And if you want to see how bad corruption gets, just watch some raw travel footage on YouTube of Westerners exploring these places.

How are we measuring corruption? There’s an index called the CPI (Corruption Perceptions Index) that does a pretty good job. It scores and ranks countries by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, as assessed by experts and biz execs.

It’s not an exact science, but it’s probably more accurate than armchair dipshits Russian bots on X/Twitter speculating. A 2002 study reported a “very strong significant correlation” between the CPI and 2 other proxies for corruption: black market activity and overabundance of regulation.

All 3 metrics significantly correlate with real GDP per capita… higher real GDP per capita is correlated with lower corruption (no surprise). There are also strong links between lower corruption and equal treatment before the law (justice).

A 2020 study “Statistical Analysis on the Correlation of Corruption Perception Index and Some Other Indices in Nigeria” reported strong correlations between low corruption and HDI (Human Development Index), Global Peace Index (GPI), and Global Hunger Index (GHI)… lower corruption = better metrics here.

There is also a relationship between corruption and income inequality… but that’s because you have corrupt ruling classes in undeveloped “shit hole” countries and they horde all the money while massively interfering with free markets, capitalism, innovation, and prosocial contributions.

Income inequality is something I could rant on for days… but basically: income inequality is a REALLY GOOD THING in free market, capitalist, low corruption countries (because everyone benefits from the innovation of super-producers who are incentivized to create more so they can earn more)… the rising tide lifts the bottom to the extent that the “poorest people in the U.S.” are living like Kings compared to the richest people in Somalia.

Income inequality is a REALLY BAD THING in high corruption countries (and is in part, a byproduct of the actual corruption). What’s happening here? Corruption disincentivizes people from innovating, starting businesses, etc. because there’s nothing to gain… the corrupt just steal or block it.

Anyways, I’m going to present an exploration into the underlying genetics of corruption and propose some ideas that could be implemented to potentially attenuate or eradicate corruption globally.

FYI: I am not arguing that there’s a “single corruption gene.” If you’re the type to say “show me the corruption genes,” then you are too dumb to even read this… many tiny genetic differences add up to create a distinct holistic picture that can vary significantly in terms of corruption from one nation to another.

I. Introduction & Theoretical Background

Government dysfunction and corruption vary widely around the world. A provocative hypothesis is that these differences are partly downstream of aggregate population genetics – in other words, the genetic composition of a society (via its effect on psychology and behavior) might influence its governance quality.

Key behavioral traits such as intelligence, impulsivity (self-control), time preference, and conscientiousness have significant heritable components and could plausibly affect a society’s ability to create honest, effective institutions.

For example, a population with higher average cognitive ability and future orientation may be better equipped to establish rule of law and resist petty temptations, whereas populations predisposed (genetically or culturally) to short-term thinking or clannish loyalty might struggle with chronic corruption.

This idea is controversial. Social scientists traditionally emphasize historical, economic, and cultural explanations for corruption (e.g. colonial institutions, resource wealth, war, etc.). However, a growing body of literature explores whether underlying genetic differences in psychological traits play a role in national outcomes.

The hypothesis is not deterministic – genetics act in probabilistic interplay with environment – but it suggests that genetically influenced trait distributions set the “baseline” upon which institutions must operate.

In this report, we examine theoretical links between genetics and corruption-related traits, review empirical evidence (and its limitations), and compare global regions to assess how population characteristics correlate with corruption indices.

We also discuss dysgenic trends (decline in genetic quality) and mutational load (accumulation of harmful mutations) as potential factors over time. The goal is a comprehensive, analytical overview – acknowledging the sensitive nature of this topic and the need for cautious interpretation.

II. Genetically-Influenced Traits & Institutional Quality

Several psychological traits known to affect ethical and long-term behavior are moderately to highly heritable. Below we consider each trait in turn, examining how it might impact governance.

A.) Intelligence (Cognitive Ability)

Average intelligence (IQ) is a strong candidate for influencing corruption levels. Higher cognitive ability generally improves problem-solving, abstraction, and understanding of complex social rules.

At a societal level, numerous studies find that countries with higher average IQ have lower corruption (Intelligence and Corruption).

For example, one cross-country analysis reported that national IQ correlates negatively with perceived corruption (raw correlation around –0.6) (The Intelligence of Nations).

The proposed mechanism is that more intelligent populations tend to have longer time horizons and better foresight, making individuals less willing to compromise long-term societal benefits for short-term personal gain.

In other words, intelligent people discount the future less, so they are more likely to resist a quick bribe that could undermine the rule of law they rely on in the long run. Importantly, research suggests this relationship is non-linear.

Research across 171 countries found a pronounced threshold effect: below a certain IQ level, corruption remains high regardless of small IQ differences, but beyond that threshold, higher IQ leads to sharply lower corruption.

Specifically, they identified a national IQ of about 83 as a tipping point. Countries with IQs below ~80–83 uniformly struggle with widespread corruption, such that an IQ 70 country is about as corrupt as an IQ 80 country.

But once average IQ crosses the threshold into the mid-80s and above, further cognitive gains produce real improvements in governance. In the lower range “it does not matter whether the national IQ is below 70 or just above 80” – corruption stays high – but above an IQ of ~83, increased intelligence predicts more success at curbing corruption.

This finding aligns with a “formal operational thinking” requirement: only when a critical mass of the population can engage in complex, abstract reasoning (a cognitive stage identified by Piaget) can society support truly impersonal, honest institutions.

Below that, governance may revert to personal favors and nepotism, as many citizens and officials simply do not internalize the long-term, abstract benefits of fighting corruption.

It’s worth noting that intelligence is highly heritable (twin studies show ~50–80% heritability in adults (Heritability of IQ), and population IQ differences have proven quite robust. While environment (education, nutrition, etc.) has a huge effect on absolute IQ levels, researchers like Rindermann, Lynn, and others have documented persistent gaps between nations and strong correlations between national IQ and indices of development.

One recent extensive analysis demonstrated that average cognitive ability is the single strongest national-level predictor of societal outcomes including economic development and governance quality. In fact, it argued that countries cannot effectively curb corruption unless their national intelligence is above the threshold – below that, even intensive anti-corruption efforts may falter.

This is a bold claim, but it echoes the threshold model evidence discussed above. The intuition is that a base level of cognitive “human capital” is needed for rule of law to take root. With too low a cognitive level, a society might lack enough experts, honest administrators, or even citizens who understand and demand good governance.

Mechanistically, higher intelligence in a populace can bolster institutions via multiple channels: better education outcomes, more competent civil servants, greater innovation in monitoring and enforcement, and a populace that can evaluate and hold leaders accountable.

Cognitive ability also correlates with greater patience and self-control, as well as general prosocial behavior (when controlling for other traits). Of course, intelligence alone doesn’t guarantee honesty – clever people can concoct sophisticated corruption too – but at a macro scale, smart societies tend to have the foresight to build stronger institutions, and they may culturally emphasize meritocracy over nepotism.

B.) Impulsivity & Time Preference

Impulsivity (low self-control) and high time preference (strong preference for immediate gratification over future benefits) are trait dimensions likely linked to corruption. Intuitively, corruption often entails a present reward (a bribe, embezzled funds) at the expense of future costs (legal risks, loss of reputation, damage to society).

Individuals (or cultures) with a short time horizon may thus be more prone to engage in corrupt acts, discounting the long-term harm or the probability of punishment.

Impulsivity has a substantial genetic basis – studies indicate that aspects like inability to delay gratification and risk-taking are moderately heritable (twin-based heritability estimates for various impulsivity measures range roughly 20–50%) (Twin study on heritability of activity, attention, and impulsivity).

Time preference (patience) also shows genetic influence; for example, a German twin study estimated ~23% of variation in patience is explained by genetics (Heritability of Time Preference: Evidence from German Twin Data).

These traits likely evolved in response to environments: in uncertain or harsh conditions, a “fast life history” strategy (live fast, reproduce early, value the present) can be advantageous, whereas stable environments favor planning for the future.

Some evolutionary psychologists have theorized that populations differ in average time preference due to historical selective pressures. For instance, populations whose ancestors endured long winters or consistent agriculture might have evolved lower impulsivity and greater future-orientation, whereas those in more unpredictable climates might be predisposed to seize immediate opportunities.

Such differences, if they exist, would have profound social implications – a very impatient populace may have trouble sustaining anti-corruption norms that require patience (like waiting your turn, investing effort now for clean institutions later).

Though hard direct evidence is scarce, cross-country data on time preference and behavior support the idea of variation. The Global Preference Survey (which measured impatience across 76 countries) found sizable differences in average willingness to delay gratification.

These differences correlate with development: generally, richer, better-governed countries had populations that were more patient and risk-averse, whereas many poorer countries exhibited higher discount rates (less future orientation).

In practice, high impulsivity can foster corruption at both the individual and societal level. Officials with poor self-control may grab illicit gains the moment they appear. Citizens who heavily discount the future might be more tolerant of corrupt leaders (focusing on immediate patronage benefits rather than long-term policy).

A society characterized by “live for today” attitudes could struggle to implement reforms that only pay off down the road. By contrast, a genetic-behavioral pattern of restraint and deferred gratification (whether culturally or genetically influenced) supports the patience needed to, say, forego a bribe because one values the long-term credibility of the institution.

Notably, intelligence and time preference are interrelated – higher IQ people tend to exhibit lower impulsivity, in part because executive function (brain mechanisms for self-control) improve with cognitive ability.

This means some of the IQ-corruption link may actually operate through time-horizon: smarter populations think further ahead.

Indeed, Niklas Potrafke (2011) explicitly argued that the IQ effect on corruption exists because “intelligent people have longer time horizons” .

Thus, cognitive capacity and impulsivity together form a nexus of “strategic thinking” traits that influence corruption.

C.) Conscientiousness & Rule-Following

Another relevant trait is conscientiousness, one of the Big 5 personality dimensions. Conscientious individuals are generally dutiful, self-disciplined, and compliant with rules or norms.

At a national scale, if a population’s average conscientiousness is high, one would expect more citizens who feel internally compelled to follow laws and ethical standards – which could lower corruption.

Conversely, low conscientiousness (more lax attitude toward rules) might predispose a society to bribery, cheating, and nepotism.

Personality traits like conscientiousness are moderately heritable (≈40–50%) (Heritability Estimates of the Big 5 Personality Traits), so genetic differences could lead to population-level differences in these characteristics. It’s challenging to measure national personality objectively – self-report surveys have issues – but some international studies have been done.

Interestingly, self-reported conscientiousness scores do not always match outcomes (for example, some high-corruption countries report very high conscientiousness in surveys, perhaps due to differing response styles).

So we rely more on indirect inference: behaviors related to conscientiousness, such as punctuality, rule adherence, work ethic, etc., do show variation across cultures that might reflect underlying dispositional differences.

One facet of conscientiousness is honesty/propriety (sometimes measured separately as “Honesty-Humility” in HEXACO model). To the extent this trait varies, it could directly affect corruption.

There is evidence that the propensity to cheat or engage in antisocial behavior has genetic underpinnings – for example, behavioral genetics studies find traits like antisocial personality, aggressiveness, or lack of impulse control (which relate to unethical behavior) have heritabilities in the 30–50% range.

If an entire population has a higher prevalence of such dispositions, it may face greater corruption challenges.

Social trust is also crucial for clean institutions. High-trust societies (where people generally believe others are honest and fair) can more easily develop low-corruption governance, because both officials and citizens behave with the expectation of mutual honesty.

Trust has cultural roots but also overlaps with personality (people high in Agreeableness or low in Neuroticism tend to trust more). Twin studies suggest generalized trust is partly heritable too (on the order of 20–40%).

A low-trust society can become a self-fulfilling prophecy of corruption: if everyone assumes others are cheating, the incentive to be the rare honest player diminishes.

Genetically influenced predispositions toward skepticism or trust could thus tilt a society toward a high-corruption or low-corruption equilibrium respectively, though clearly historical factors (like conflict or effective state institutions) also shape trust.

D.) Collectivism, Kinship, Nepotism Tendencies

A different angle on corruption comes from family structure and collectivist vs. individualist orientation. In societies where people’s loyalty to family/clan is paramount (collectivist cultures), officials often favor relatives and friends (nepotism) rather than treating everyone impartially.

In more individualist societies, people are inclined to treat others on merit or as equals under the law, supporting impartial institutions. These cultural orientations have some deep historical and even genetic correlates.

Research by Jha and Panda (2017) found that countries with individualistic cultures have significantly lower corruption levels (Individualism and Corruption).

Crucially, they instrumented culture using historical pathogen prevalence and genetic distance (distance from populations of European ancestry) to argue the relationship is at least partly causal.

Their results suggest that certain long-standing cultural-genetic factors (e.g. exposure to disease, which can select for collectivist tight-knit behavior, or ancestral migration patterns) induced differences in individualism, which in turn affect corruption.

Overall: Individualism (which tends to go along with out-breeding and weaker kin bonds) predicts lower corruption, whereas strong kin-based collectivism correlates with higher corruption.

One mechanism here is in-group favoritism. Anthropologists note that in many high-corruption societies, people feel a moral duty to favor their relatives and ethnic kin – hiring them, bending rules for them – and a corresponding distrust of “outsiders.”

This undermines universalistic rule of law. By contrast, more individualistic societies enforce rules more uniformly. What causes some groups to be more clannish?

One factor is marriage patterns. A landmark study in 2019 showed that rates of cousin marriage (consanguinity) predict corruption levels: societies with prevalent cousin-marriage and tightly knit kin groups have more nepotism and corruption, whereas those with a history of out-breeding (marrying outside the family) have more open, transparent institutions (Kinship, Fractionalization and Corruption).

In-marriage creates closed genetic clans, boosting loyalty to family at the expense of civic fairness. Out-marriage, by increasing genetic mixing and expanding social networks, encourages treating non-kin as peers, thus fostering impartial norms.

Akbari et al. (2019) not only found a robust correlation across countries, but using historical exposure to the Church’s marriage bans as an instrument, they provided evidence that more out-breeding causally led to lower corruption by breaking down kin-based loyalties.

Genetics and culture intermingle in these kinship effects. Extended periods of outbreeding can also alter allele frequencies related to social behavior (essentially selecting for a more prosocial, trusting disposition beyond one’s clan).

Meanwhile, centuries of strong inbreeding might increase what some researchers call “clannishness” – possibly even through higher genomic homozygosity or accumulation of certain personality-linked genes in subpopulations.

While the genetic mechanism is speculative, the outcome is clear: populations with a tradition of strong kin loyalty tend to have higher corruption. For example, many Middle Eastern and North African societies (with historically high cousin-marriage rates) score poorly on corruption indices and rely heavily on patronage networks.

In contrast, Northwestern European societies (which for over a millennium practiced outbreeding due to religious norms) are among the least corrupt, and they exhibit a strong sense of impersonal duty.

One study notes that impersonal trust and cooperation in Europe rose after outbreeding increased, paving the way for modern honest governments.

In total: Various genetically-influenced traits – cognitive ability, impulsivity/self-control, conscientiousness (rule-following), and tendencies toward kin favoritism vs. universalism – all plausibly affect a society’s corruption outcomes. These traits are polygenic (shaped by many genes) and differ somewhat among populations.

III. Empirical Data: Genetics, Behavior, Corruption

A.) Intelligence & Corruption: Strong Correlations

Empirical cross-country studies consistently show that national IQ correlates strongly with governance indicators.

Researchers have estimated that national cognitive ability has a 0.6–0.7 correlation with Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

Higher IQ nations tend to score better (higher) on the CPI, meaning less perceived corruption. This holds even when controlling for GDP per capita and other variables – indeed, some analyses suggest IQ is an independent predictor of lower corruption.

“If the IQ increases by one point, corruption as measured by the reversed CPI decreases by about 0.1 points. Against the background of the standard deviation of about 12 points of the IQ this is a numerically substantial effect: when the overall IQ increases by one standard deviation, the reversed CPI decreases by about 1.2 points, more than half a standard deviation.” — Potrafke (2011)

The non-linear pattern discussed earlier also emerges in data. Using CPI scores, researchers demonstrated that countries below roughly the 85 IQ threshold uniformly have very high corruption, whereas almost all countries that are relatively corruption-free have above-average IQ populations.

In an analysis of 75 low-corruption countries, only two had national IQs below 80 (Barbados and Bhutan, which we’ll discuss as special cases) – the rest all had IQ≥~90 (Intelligence of Nations).

This led to the hypothesis that “a very high level of corruption freedom – as is common in the Western world – is unattainable without a certain level of intelligence in the population.”

In concrete terms, data from Transparency International and IQ studies suggest that a country with an average IQ of 100 (typical of developed nations) has the potential for very low corruption (CPI scores in the 70s–80s out of 100), whereas a country with average IQ of 75 (typical of least-developed nations) almost always has entrenched corruption (CPI scores below 30).

It’s critical to note that correlation is not causation. High-IQ countries also tend to be wealthier and historically were industrialized earlier, so one must be careful. However, some longitudinal evidence bolsters the causal interpretation: improving education and cognitive skills in a population precedes improvements in governance.

My take? Wealthy countries are wealthy BECAUSE OF THEIR UNDERLYING GENETIC COMPOSITION. This leads to things like “GOOD EDUCATION.” The “GOOD EDUCATION” is secondary to the genetic makeup. And a good education is meaningless if you are cognitively incapable of absorbing the information.

So there’s a feedback loop: Smart people → smart teachers → smart kids → lower corruption… If you insert different DNA in this chain (e.g. lower IQ kids) it doesn’t matter how “good the schools” or how “good the teachers” are… and this aligns with data suggesting that some of the most well-funded schools in the U.S. are among the poorest performers (e.g. LeBron James School with Zero Kids that Can Pass a Basic Math Test).

I could take a group of kids with almost zero resources… but if they are high IQ kids, could probably teach them enough to dominate most basic tests. In fact, I might not even need to teach them… might just be intuitive.

Anyways, the “Asian Tigers” (South Korea, Singapore, etc.) dramatically raised education levels and saw corruption fall as those higher-skilled generations entered government.

In contrast, many resource-rich low-IQ countries failed to improve governance despite wealth, implying that money alone (or even external anti-corruption advice) couldn’t overcome the human capital gap.

Beyond IQ, studies have looked at allele frequencies and polygenic scores related to cognition or behavior. This research is nascent and politically charged.

A few analyses of modern genomics data have computed polygenic scores for educational attainment or cognitive ability in different ancestral groups.

They do find population differences (for example, East Asian samples often slightly higher on Euro-derived education polygenic scores, African samples lower, with Europeans intermediate) – but these must be interpreted with extreme caution due to methodological biases.

Nevertheless, such work hints that genetic propensity for certain traits is not evenly distributed worldwide, which could contribute to the observed IQ and development differences.

If future research confirms these genetic differences in cognitive ability, it would further support the link between population genetics and institutional quality (since we already know cognitive ability links to corruption).

NOTE: Intelligence is ONE trait linked to corruption (higher IQ generally = lower corruption). Doesn’t mean there are zero high IQ corrupt people… just lower rates than lower IQs. Also doesn’t mean that intelligence is the only trait linked to lower corruption. The way to think about this is: the holistic genetic picture that yields lower corruption societies tends to overlap with higher IQ.

B.) Personality, Culture, Corruption Data

Direct country-level measures of traits like impulsivity or conscientiousness are harder to come by, but we have proxies. The World Values Survey and other international surveys include questions that relate to time preference, trust, and respect for norms.

Countries that rank high in “thrift” (saving for the future) and “moral discipline” tend to have lower corruption. For example, Japan and Scandinavia score high on valuing thrift/honesty and indeed have low corruption, whereas many African and Latin American countries score lower on those values and suffer higher corruption.

These differences align with both cultural and possibly genetic influences on personality. One interesting dataset is the Global Preferences Survey (GPS), which quantified patience and risk-taking worldwide.

The GPS found that countries like Sweden, Germany, China have among the highest patience (low time preference), whereas countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Middle East had some of the lowest patience scores (Global Preferences).

Patience correlates with many outcomes – notably, high-patience countries have higher GDP per capita and better governance on average. It’s reasonable to infer that populations inclined to wait for larger future rewards are also more willing to forego the quick gains of corruption in favor of the long-term benefits of a clean economy.

On the collectivism vs. individualism front, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions database and others give each country a score. Individualist societies (e.g. UK, USA, Australia) generally have lower levels of petty corruption than collectivist societies (e.g. Pakistan, Nigeria, Guatemala).

Jha and Panda’s analysis formally showed that a one standard deviation increase in individualism was associated with a substantial decrease in corruption, even when controlling for income (Individualism and Corruption). Interestingly, their use of genetic distance from the US/UK population as an instrument implies a deep-rooted component to this cultural trait.

Genetic distance encapsulates many historical and evolutionary differences; the finding suggests that populations more closely related to the Anglo-European cluster (which are highly individualist) tend to have adopted similar low-corruption norms, whereas those more distant (with different ancestral environments) lean collectivist and more corrupt.

While this is a broad generalization, it highlights how genes and culture co-evolve: institutions like impartial bureaucracy thrived in societies that culturally (and perhaps genetically) favored individual merit and trust in strangers, rather than clannish favoritism.

A striking empirical link involves consanguinity rates and corruption. Data show that countries with higher rates of cousin marriage (common in parts of the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia) almost uniformly score poorly on corruption indices.

For instance, Pakistan, Yemen, and Nigeria have very high consanguinity and also rank among the most corrupt nations. In contrast, countries with long histories of outbreeding (Western Europe, North America, Northeast Asia) dominate the top of the clean governance rankings.

Akbari et al. documented this correlation and even within countries, regions with more cousin marriage have more nepotism and local corruption. Their causal argument was that inbreeding creates tight kin units that promote nepotistic norms, undermining rule of law.

This is a socio-genetic factor: it’s not a specific gene but the structure of genetic relatedness in society that matters. The genetic homogeneity within clans effectively pits families against the broader society for resources, leading to patronage systems.

By contrast, outbred societies (like much of Europe after the medieval era) forced people to cooperate beyond kin, laying a foundation for impartial institutions. This is a powerful example of how “aggregate population genetics” – in this case, the distribution of kinship links – can downstream influence corruption levels.

C.) Dysgenics & Mutational Load in Data

Dysgenics

The concept of dysgenics – a decline in genetic quality due to differential reproduction – has been applied most often to intelligence. Evidence from demographic data in many countries shows a negative correlation between IQ and fertility: individuals with higher education and cognitive ability tend to have fewer children, especially in developed societies.

Over time, this could slowly reduce the genetic potential for intelligence in the population. Scholars like Richard Lynn and Michael Woodley have attempted to quantify this effect.

For instance, by examining fertility rates by IQ, one can calculate a selection differential and an expected IQ change per generation. Some estimates suggest that genetic IQ might be declining by roughly 0.5 to 1 point per generation in many countries due to dysgenic fertility.

One analysis estimated a ~2 IQ point decline per century in Western populations from combined effects of relaxed selection and lower fertility of the more educated (Are We Getting Dumber?). If true, dysgenic trends could gradually erode the capacity for good governance.

A population even 5 IQ points lower on average might have fewer highly gifted individuals to run complex institutions and a larger fraction struggling with understanding civic rules, which could increase systemic inefficiency and corruption.

Some have theorized that historical civilization declines (the fall of Rome, etc.) had a demographic component – the more capable segments of society failed to reproduce at replacement rates, leading to a population less able to maintain complex state structures.

Today, this concern is often raised for advanced countries: as educated people have very few children, could the long-term result be governance issues or a need to import talent?

The empirical evidence for current dysgenics includes careful demographic-genetic modeling. One 2022 study compiled data from 62 countries and projected IQ changes to 2100, finding that many nations (especially in East Asia and Europe) will see genetic IQ declines unless patterns change.

They also pointed out that high-IQ populations are aging and shrinking, while low-IQ, high-fertility populations (notably in parts of Africa and South Asia) are expanding rapidly. This could shift the global balance of traits relevant to corruption.

Mutational Load

Mutational load is harder to observe directly, but genomic studies have found differences in the burden of deleterious mutations among populations. Notably, due to the Out-of-Africa migration and serial bottlenecks, Eurasian populations carry slightly less overall genetic diversity but may have accumulated more weakly harmful mutations — a recent 2016 PNAS paper showed mutational load increases with distance from Africa (Distance from sub-Saharan Africa predicts mutational load).

However, Africans face their own mutational loads from high endemic disease and other factors. The net effect on behavioral traits is still speculative. Some researchers argue modern medicine and relaxed selection allow more mutations with negative brain effects (e.g. neurodevelopmental mutations) to persist, possibly increasing rates of mental disorders or reducing average “genetic fitness” for intelligence.

One would expect high mutational load to manifest as more variance and more extreme cases (e.g. a slight uptick in those with poor impulse control or cognitive deficits). So far, evidence for a large mutational load impact on IQ is mixed – one analysis found only a very small decline attributable to new mutations per generation, and noted that if mutational load were greatly harming intelligence, we would likely see clearer drops in cognitive test scores already.

Still, it remains an open area of research. In terms of corruption, if high mutational load correlates with more individuals prone to erratic or antisocial behavior, it could subtly worsen institutional quality. But empirically, this is not yet demonstrated; it’s more a theoretical possibility given what we know about mutations affecting brain function.

Overall: Empirical findings lend considerable support to the idea that aggregate traits matter. High-IQ, patient, individualist populations achieve better governance on average. More clannish or lower-capability populations struggle with corruption, and simply transplanting Western legal systems into those contexts often fails to eliminate corrupt practices.

RELATED: Gene Editing & Therapy for Obesity: Top Targets (2025)

IV. Global & Regional Comparisons

Broad Regional Patterns

We can observe the interplay of genetics and corruption by comparing world regions on key variables. Below is an overview of approximate average IQ and recent corruption levels (CPI scores) for major regions, along with notable trait or cultural factors.

1.) 🌏 East Asia (China, Japan)

IQ: 100–105 (High)

Corruption: Moderate–Low (China CPI: 45, Japan CPI: 73)

Traits: High cognitive ability; Collectivist yet disciplined; Long-term economic planning

2.) 🌍 Northern & Western Europe

IQ: 98–100 (High)

Corruption: Very Low (Sweden CPI: 83, UK CPI: 73)

Traits: Individualistic, High-trust societies; Strong historical Protestant ethic; High conscientiousness and transparency

3.) 🌍 Southern & Eastern Europe

IQ: 90–95 (Medium-High)

Corruption: Moderate (Italy CPI: 56, Bulgaria CPI: 43)

Traits: Somewhat collectivist and familial; Historical clan-based patronage (Balkans)

4.) 🌍 Middle East & North Africa

IQ: 80–85 (Modest)

Corruption: High (Saudi Arabia CPI: 51, Egypt CPI: 30)

Traits: High kinship intensity (common cousin marriage); Tribal/clan loyalty outweighs formal rules

5.) 🌍 South Asia (India, Pakistan)

IQ: 80–85 (Modest)

Corruption: High (India CPI: 40, Pakistan CPI: 28)

Traits: Hierarchical, collectivist cultures; Historically low literacy, short-term economic outlook

6.) 🌍 Sub-Saharan Africa

IQ: 70–80 (Lower)

Corruption: Very High (Nigeria CPI: 24, Kenya CPI: 32)

Traits: Short-term focus, high impulsivity; Strong ethnic/kin loyalty, trust limited to in-group

7.) 🌎 Latin America

IQ: 85–90 (Medium)

Corruption: Moderately High (Chile CPI: 67, Brazil CPI: 38)

Traits: Mixed ancestry (European/indigenous/African); Machismo culture, moderate time-preference; Governance better with higher European influence

8.) 🌎 Caribbean (Afro-descendant)

IQ: ≈80 (Modest)

Corruption: Varied (Barbados CPI: 65, Haiti CPI: 17)

Traits: Small island contexts; Better governance in former British colonies (Barbados, Bahamas); Extreme corruption elsewhere (Haiti)

The pattern is stark: regions with higher cognitive ability and more individualist or trust-based cultures (East Asia, West Europe) have generally low corruption.

Regions with lower cognitive ability and strong clannish or short-term oriented cultures (Africa, parts of Asia and Middle East) have high corruption.

Regions in between (e.g. Eastern Europe, Latin America) show intermediate outcomes, consistent with intermediate trait profiles.

These are broad brushstrokes, and within each region there is variance and important exceptions:

A.) East Asia

Countries like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore boast very high average IQs and have built efficient, low-corruption states (Singapore in particular ranks 3rd least corrupt worldwide in 2025).

China, with a slightly lower CPI, still far outperforms most countries at similar income levels in corruption control – perhaps reflecting the high skill of its bureaucracy (a legacy of meritocratic exams) and a cultural respect for authority, despite being a one-party state.

One could argue the largely homogeneous high-IQ population of Chinese (Han) people provided a basis for an effective state; when the political will arose (post-1990s) to curb corruption, the population’s capacity could implement it.

Compare that to Mongolia (ethnically related but smaller and less developed): IQ around 97, CPI ~33 – showing that good population traits alone aren’t enough without governance structures.

Nonetheless, ethnic Chinese diaspora communities around the world (from Malaysia to Trinidad) often bring comparatively lower corruption and higher enterprise than local averages, hinting at a persistent group advantage in certain traits (education focus, future orientation).

B.) Western/Northern Europe & Anglosphere

These societies consistently have among the world’s lowest corruption. Examples: Denmark, Finland, New Zealand top the CPI index (scores ~88/100). They also have uniformly high national IQs (~98–100).

Culturally, these countries emphasize individual responsibility, have low power-distance (egalitarian), and very high social trust. Historically, their populations underwent centuries of outbreeding and adherence to rule-based religion (e.g. Protestantism), which some scholars argue selected for greater conscientiousness and civic-mindedness.

Whether by genetic evolution or cultural evolution (likely both), Northwestern Europeans developed a strong “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) profile that values impartial rules over nepotism. Even when transplanted abroad, these populations created relatively clean governments (e.g. Canada, Australia rank high on CPI).

The Anglo countries have slightly more diversity today, but their institutions were initially built by predominantly NW European founders, arguably reflecting that heritage’s influence.

C.) Southern/Eastern Europe

This includes the Mediterranean nations and post-Communist states. They have somewhat lower average IQs (mid-90s in Italy, Spain; as low as mid-80s in the Balkans) and notably higher corruption than Northern Europe.

For example, Italy and Greece struggle with corruption (CPI in the 40s-50s) despite being developed – a phenomenon often attributed to a culture of family loyalty, patronage, and historical governance by empires or the Church rather than bottom-up democracy.

The Italian South, with higher rates of cousin marriage historically and possibly more Middle Eastern genetic influence, is more corrupt than the North. This hints that even within Europe, micro-differences in population history (and perhaps genetics) align with institutional quality.

Eastern Europe (e.g. Russia, Ukraine, the Balkans) also has a legacy of clan networks (boyars, communist nomenklatura) and an average IQ around low-90s, matching their moderate corruption levels.

However, education is rising and some countries (Estonia, Slovenia) have significantly reduced corruption, showing culture/policy can improve things if population capacity is sufficient.

D.) Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Most of the MENA region scores poorly on corruption, with CPI averages in the 20s and 30s. Genetically, these populations are a mix of Caucasian, Arab, and African lineages, with average IQs usually estimated in the 80s.

A key factor here is intense kinship structures – many MENA societies have 20–50% of marriages occurring between cousins or close kin. This has arguably ingrained a strong nepotistic mindset over generations. A public office is seen as an instrument to enrich one’s family or sect, not as a neutral trust.

Even oil-rich Gulf states, despite high human development, rank mediocre on corruption (e.g. Saudi Arabia CPI 51, UAE 67) because tribal/family networks dominate business and governance.

Some MENA countries have tried anti-corruption drives (often via authoritarian crackdowns), but progress is limited, arguably because the underlying social norms – possibly reflecting deep-rooted personality predispositions – favor favoritism.

In contrast, a unique outlier is Israel (average IQ ~95 and a genetically diverse mix of European, Middle Eastern, and North African Jews): it scores relatively well on corruption (CPI 63) for the region.

Some think that the lower corruption in Israel is from institutions and culture… but these are downstream of the population genetics. Israel is known to have had far less inbreeding (consanguinity) than neighboring countries and is genetically diverse.

E.) South Asia

Countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh have moderate corruption (India CPI 40, Bangladesh 25) consistent with their modest cognitive metrics (IQs in the low 80s). These populations are genetically diverse but generally fall between Europeans and Sub-Saharan Africans in many allele frequencies.

Traits often observed include high collectivism (caste and family loyalty) and relatively high impulsivity (e.g. lower savings rates than East Asia).

India’s case is instructive: despite a sizable high-IQ elite, the overall population’s limited literacy and education until recently kept institutional quality low… the main reason India has plenty of “high IQ” people has to do with its large population (~1.4 billion people).

It actually has much lower rates of “high IQ” per capita than other countries. And many Indians will privately admit that corruption is woven into daily life, from traffic bribes to nepotistic hiring, suggesting a tolerance that may have cultural-genetic origins (centuries of extractive colonial rule and caste endogamy shaped behavior).

Indians who emigrated to Western countries (bringing their genetic predispositions) often thrive under good institutions and are law-abiding; yet when similarly educated people remain in India, they must navigate (and sometimes succumb to) a corrupt system.

This essentially is a selection effect wherein the elite top 0.1% of Indians leave India (thus the LOWER CORRUPTION GENETICS migrate out of India and India is left with its standard-genetic corruption mix). The combination of elite Indians leaving and its “caste system” is far from ideal.

One could argue that if India’s population had the same aggregate traits as, say, Japan, its corruption would be far lower even under the same system.

F.) Sub-Saharan Africa

This region consistently ranks as the most corrupt in the world. The average CPI for Sub-Saharan African countries is around 32/100, and many are below 25 (e.g. DR Congo, South Sudan) – indicating rampant corruption.

Correspondingly, measured IQs in many African nations are very low (some studies put the median around 75, though there’s debate about test bias). Even taking a higher estimate (~80 after adjusting for environmental factors), it’s clear that the population faces developmental challenges.

Genetic factors for IQ (like allele frequencies associated with educational attainment) are still being studied in African populations, but the preliminary data suggests fewer high-IQ variants (likely due to less historical selection for cognitive-intensive work compared to Eurasia, and perhaps more emphasis on survival traits like disease resistance).

Additionally, Africans have shorter life expectancies and historically high mortality – conditions that favor a fast life-history strategy: earlier reproduction, present-oriented behavior. Indeed, observers often note that “tomorrow matters less” in some African contexts – a mindset that sadly is conducive to corruption (why build clean institutions for the future if the present is so uncertain?).

Culturally, African societies are strongly collectivist – loyalty to one’s ethnic group or family is paramount. The nation-state is a newer, weaker concept, so stealing from the “state” to help your kin is not always strongly condemned.

All these factors create a perfect storm for corruption. Even well-intentioned reforms (new anti-graft agencies, democratization) often falter. Nigeria is a case in point: despite high oil revenues and numerous anti-corruption campaigns, it remains one of the most corrupt large countries (CPI 24).

The population’s low average education and enduring patronage networks (often along tribal lines) mean that when one corrupt official is removed, another often takes his place – the systemic demand for favoritism remains.

Some African countries do relatively better – Botswana (CPI 61) and Seychelles (66) are examples. Botswana is often cited as having a somewhat higher national IQ (~82) and benefitted from a small, cohesive, genetically homogenous population (Tswana people) with enlightened leadership post-independence.

Botswana has a low history of inbreeding and has historically been relatively peaceful (violent/aggressive behavior may not have been a survival advantage).

Seychelles has a unique multiethnic population (African, French, British, Indian, Chinese, etc.), the “flounder effect” (small selected groups of initial settlers that became the majority — may have had traits of lower corruption), etc.

In general, Africa illustrates the difficulty of imposing low-corruption institutions on a society that, likely due to genetics (plus environment as a reinforcing feedback loop), faces constraints in achieving them.

This lends credence to the idea that population traits set the boundaries of possible governance outcomes.

G.) Latin America

Latin American countries mostly fall in the middle range on corruption indices (CPI 30–50), with a few doing better (Chile 67, Uruguay ~74 – both significantly less corrupt). The populations here are mixed-race (European, Native American, and African ancestry). Average IQs are in the 80s or low 90s.

Culturally, many Latin societies have a blend of European institutions with local personalistic tweaks – known as “amiguismo” or favor-trading among friends. There is often an informal norm that bending rules is acceptable to help one’s network.

Genetic influences might be seen in how countries with heavier European ancestry (Argentina, Chile, Uruguay) tend to have somewhat stronger institutions than those with more indigenous or African admixture (Honduras, Haiti).

For instance, Chile (population largely of Spanish and indigenous descent, with an average IQ around high-80s/low-90s) has remarkably low corruption for a non-First-World country. Chile’s success is usually attributed to good policies and a relatively homogeneous middle-class society, but underlying that was a population with higher education and slightly more individualist culture than many peers.

On the other hand, Haiti, with predominantly African ancestry (and an average IQ likely in the 70s or low 80s), is essentially a failed state plagued by corruption.

Notably, Haiti shares ancestry with many in West Africa, and its corruption level (CPI 17) is comparable to the worst African states – suggesting that even under different geography, the combination of low human capital and extractive colonial history led to the same outcome.

Meanwhile, nearby Barbados (also predominantly African-descended) achieved a relatively clean, stable government (CPI 65, one of the best in the Western Hemisphere).

Barbados’ secret was arguably its British-inherited institutions and small size – it maintained strict law-and-order, good schooling, and perhaps had some genetic selection (its population, while African in origin, might have non-randomly self-selected traits through the rigors of colonial era and a degree of admixture).

Analysts have even noted that Barbados and some other Caribbean islands effectively imported governance from Britain and “imported intelligence” in the form of education and managerial expertise, allowing them to punch above what one might predict from raw genetic averages.

This highlights that external intervention (or cultural transplantation) can mitigate internal limitations to an extent – but without it, countries with similar population stock (like Haiti or Jamaica) fared worse.

Shared Genetics Across Borders?

Comparing the “same” ethnic group across different borders was once seen as an ideal way to isolate environment from genes.

Yet modern population genetics and historical demography remind us that a group’s gene pool can change over just a few generations if selected subpopulations leave, certain families are purged, or fertility patterns skew strongly.

North vs. South Korea is an extreme example. While 1945 Koreans on both sides of the 38th parallel were closely related, the subsequent waves of out-migration (often by elites, landowners, Christians) and the North’s systematic political purges likely shifted the average trait distribution.

Chinese diasporas are similarly shaped by which subsets left China (merchants, elites, refugees, etc.) and the receiving country’s immigration policy.

African diasporas in the Caribbean and the U.S. reflect centuries of forced displacement under conditions that did not replicate West Africa’s entire gene pool.

Hence, if an ethnic group in location A appears less corrupt than that same “ethnic group” in location B, environment is crucial, but the genetic baselines might also have diverged.

Over time, a host of factors—cultural norms, political selection, selective migration—can “re-sculpt” the genotype frequencies in each population.

Comparisons across borders show that environmental context can either mask or magnify genetic predispositions. The same people can be honest or corrupt depending on incentives and norms around them.

However, when we hold environment constant, as much as reality allows, we often still see echoes of population traits.

For example, even in the relatively corruption-free UK or US, studies find differences in outcomes among ethnic groups (though not necessarily corruption, which is low for all, but in things like academic achievement or income – proxies for some traits).

Those differences align with global patterns (e.g. East Asian-descended students outperform, African-descended on average underperform, with many individual exceptions).

It suggests that if all groups were put in an identical ideal system, we will see group-level differences in performance and ethical behavior stemming from innate trait distributions. But real-world complexity makes it impossible to disentangle scientifically to a degree that would satisfy most — and most wouldn’t accept this anyway.

V. The Futility of Anti-Corruption Campaigns

One sobering implication of the genetics-traits perspective is that traditional anti-corruption efforts might face structural limits in certain societies.

International organizations have poured resources into anti-corruption commissions, new laws, and civil society building in high-corruption countries.

While these can help at the margins, many such campaigns have yielded disappointing results in places like Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America.

The hypothesis here would say: if the underlying population doesn’t have enough people with the relevant predispositions (high foresight, trust, civic honesty) to sustain clean institutions, then reforms will be subverted repeatedly by “behavioral defaults.”

For instance, Nigeria’s government periodically arrests a batch of corrupt officials or launches an anti-graft war – only for corruption to resume as usual after the spotlight fades. Critics note that corruption there isn’t just a few bad apples; it’s systemic, arising from how nearly everyone operates.

One might analogize it to trying to establish a high-tech industry in a region lacking skilled engineers – without the human capital, the initiative fails. Similarly, trying to transplant Scandinavian-style clean governance into a low-human-capital society may be quixotic.

If indeed traits like average intelligence or social trust are below the threshold needed, the society may not collectively support the anti-corruption measures. They may see them as alien or impractical, and old habits return.

Empirical observation supports this: countries that have successfully reduced corruption usually had decent education and cultural preconditions to start with (e.g. Georgia and Estonia, which cleaned up post-communism, had populations with near-European levels of education and relatively homogeneous identities, plus strong external incentives to reform).

In contrast, attempts in Afghanistan or Congo, where populations face low literacy, deep ethnic divides, and ingrained patronage customs, have largely failed. From a genetics standpoint, this could be seen as natural limitations imposed by the population’s distribution of traits.

Countries are only able to curb corruption if their national intelligence exceeds a certain threshold. Below that, even significant external pressure or internal change agents struggle to gain traction.

This might explain why transparency initiatives in many African states have yielded little – the populace itself may not strongly demand or reinforce clean governance, because many individuals (rationally at their level) see more benefit in the existing patronage system (which directly ties to high time preference and narrow trust radius).

In behavioral terms, if most people would take a bribe if given the chance (due to economic need or impulsivity), then rooting out corruption is like bailing water from a leaking boat.

However, this is not to say it’s impossible to improve corruption in these regions – but it suggests the approach must involve changing the underlying characteristics over time.

That means investing in human capital (education, health) to raise cognitive ability and instill norms of integrity from a young age. It might also mean altering incentive structures so that even a person with high time-preference finds it more rewarding to behave honestly (for example, by increasing wages and enforcement in civil service).

In some cases, the only thing that has worked is outsourcing integrity – e.g. foreign advisors or peacekeepers temporarily overseeing local institutions (as in some Pacific islands or Bosnia in the 2000s).

Essentially, “importing” the behavioral tendencies of a high-integrity population to manage the affairs of a lower-integrity population. Of course, this is politically sensitive and not a long-term solution.

Finally, it’s worth considering future trajectories. If dysgenic trends continue, some worry that even currently well-governed societies could see a decline in institutional quality.

For instance, if the average genetic IQ in a European country were to drop by, say, 5 points over a few generations (due to low birth rates of the educated and continued immigration from lower-IQ regions), one might predict a rise in corruption or inefficiency, all else being equal.

There is historical precedent: some historians argue that the decline of organizational effectiveness in late Roman Empire or late Qing Dynasty coincided with adverse demographic changes. While modern science and education might offset some genetic decline, it’s a scenario to think about.

On the other hand, technological advances (like AI) might “substitute” for human capital to keep institutions functioning despite population changes.

In contrast, countries that improve their population’s genetic/trait profile could see governance gains. East Asian countries are not experiencing dysgenic fertility to the same degree (though they have low fertility, it’s fairly even across education levels), and they invest heavily in education – they might maintain or even enhance their average cognitive levels.

Some African countries are slowly raising education and reducing disease burden, potentially unlocking more of the genetic potential that was suppressed by environment (the Flynn effect – rising IQs as environment improves – is still happening in parts of Africa). If so, their corruption levels might gradually recede. But this is likely a slow, generational process.

VI. Important Notes on Genetics & Corruption

It is smart to acknowledge the limitations, uncertainties, and sensitivities surrounding this line of inquiry.

It’s not that people are actively trying to be corrupt… it’s likely baked into their DNA/genetics. Using this information to smear certain countries or groups of people is not the right thing to do.

It also doesn’t mean that EVERY PERSON in a “corrupt country” is corrupt… we should still judge people as individuals. A corrupt country may have a notable % of people that are not corrupt, just not enough people to tip the scales against corruption.

Correlation vs. causation: Many will say “correlation doesn’t prove causation” and they are technically correct. But the question to ask is “Could you ever prove causation that would satisfy most people?” The answer is no. So the smartest thing to do is just look at real-world outcomes and use first-principles thinking/analysis. Genetics is the force multiplier (culture, parenting, habits, government policies, etc.). You’ll never get definitive proof.

Data quality & biases: Data on national IQ or personality traits can be controversial. Some IQ estimates (particularly older ones for developing countries) were based on small or unrepresentative samples, potentially underestimating true ability. Critics like Wicherts have argued that Sub-Saharan African IQs, often cited around 70, may be low due to poverty and test bias, not innate capacity. It is true there’s probably some test biases… but look at real-world outcomes. You don’t need tests. Proof is in the pudding. And “IQ” is not the only correlate with corruption, but it is a major one.

Genetic heterogeneity within populations: Talking about national or ethnic genetic traits is a broad-brush approach. Within any population, there is vast genetic and behavioral diversity. Many individuals in high-corruption countries are personally very honest and capable; likewise, corrupt individuals exist even in the cleanest countries. Thus, when we say “population X has lower intelligence or higher impulsivity,” it’s a statement about averages and distributions, not a uniform label on each person. This is very true.

Political sensitivity & bias: Research on genetics and group differences has a fraught history. There are concerns about “racism” and “discrimination” and “Nazi-style eugenics.” As a result, many scientists avoid studying or even discussing possible genetic roots of behavioral differences between ethnic groups. This can lead to a dearth of open research or a bias in interpretation. For instance, scholars who do publish on this (like Lynn or Rushton in the past, or some contemporary psychologists) are often accused of ideological motives (e.g. advocating racial hierarchy).

Polygenic complexity: The genetic influences on traits like IQ, impulsivity, or conscientiousness come from thousands of genes with tiny effects, shaped by evolutionary history. While global allele frequency differences do exist (e.g. in genes for lactose tolerance or disease resistance), for behavioral traits the mapping is still preliminary. The largest GWAS (genome-wide association studies) for educational attainment have mostly been in European-ancestry samples.

Outliers & counter-examples: Some countries defy the general trend, which suggests other factors can compensate. For example, Qatar and UAE have reasonably good corruption control (CPI ~60+) despite populations that likely have only average IQ and strong kin loyalty norms. In these cases, extreme wealth and technocratic governance (often by hired foreign experts) have helped curb corruption – essentially buying integrity. But it’s about what you’d expect given the scenario (avg. genetic IQ, kin loyalty, foreign influence, extreme wealth).

Ethical considerations: Framing corruption in genetic terms is extremely controversial because it can be misused to stigmatize or even justify discriminatory policies. This should not be the goal. The goal is to get people to see the problem (genetics) and come up with effective solutions (rather than spinning their wheels in their egalitarian fantasy paradigms).

VII. Why even research genetics & corruption?

It’s necessary. Why? Because people keep playing hamster-wheel-musical-chairs with other “potential causes.” At this point if you don’t think genetics are a big cause of corruption, you are deliberately turning a blind-eye to reality.

Many erroneously think there’s some “racist” motivation behind this type of research… but the reality is it’s the exact opposite.

THE FIRST STEP IS HELPING PEOPLE SEE REALITY FOR WHAT IT IS: population-level genetics are probably the underlying cause of “corrupt countries.” Only then can we focus on solutions that might actually work/help.

Many have their heads up their asses and feign ignorance re: why certain countries are corrupt… they use this circular logic where they blame things like:

The System

Government & Leadership

Education & Schooling

Poverty

Lack of Opportunity

Policing & Law Enforcement

Blah blah blah

They don’t realize that the system, the environment, the education, the every-damn-thing they mention is a byproduct of the population-level genetics.

Are all humans the same in height, features, body composition, brain morphology? No.

Is it a stretch to think these evolved differences yield different rates of corruption? No.

Does this hypothesis align with real-world data? Yes.

Why highlight genetics as a cause of corruption?

Because people are pouring a lot of money, effort, and cognitive resources into “solving corruption” and wondering why it’s not going away! This is laughable and efforts are futile unless you are cutthroat (these people are “soft soaps”).

Doesn’t this just stoke resentment and hate between countries/ethnic groups? It shouldn’t. Is pointing out that someone has a problem with drugs/alcohol considered a bad thing? Does it stoke resentment between the addicts/alcoholics and sober people? Sometimes.

It is true that people can’t change their genetics (yet). But we still need to showcase that GENETICS is THE MOST IMPORTANT CAUSE OF CORRUPTION and likely THE ROOT CAUSE… to prevent a “money pit scenario” (endless effort, money, resources, etc. — thinking it’ll eventually help).

Acknowledge the problem: aggregate population genetics of a country leads to corruption (even if it shatters your egalitarian, detached-from-evolution-and-reality “fantasy land”).

Only after admitting there’s a genetic problem can we think of feasible strategies to: (1) cope with it; (2) fix it; or (3) leverage it to our advantage.

Worst case scenario? We can do nothing. Let’s accept that nothing can be done… we are helpless. Well then at least we: (A) understand why there are corruption gaps between countries (rather than an eternal brainstorm and confusion) and (B) can stop endless money-pit efforts to “end corruption.”

No more circular logic or mental gymnastics. Instead of pouring a time, effort, resources, etc. into “solving corruption,” maybe just stop doing this if it’s not working or sustainable. But I’m not that pessimistic… I think we can solve it.

Does this mean certain genetic groups have more corruption on average?

Yes but this is a byproduct of both evolution and selection effects (which contribute to evolution) — it’s not that they’re “trying to be corrupt.”

Different ethnic groups evolved in distinct environments for over 50,000 years… and the environment and/or random pressures led to distinct traits.

Some groups had more evolutionary and/or selective pressures for certain traits (and this may have indirectly or directly led to disparities in corruption).

Certain ethnic groups or “racial groups” (technically race is a social construct) evolved in ways that allowed corruption to sustain itself as a trait.

This does not mean some pressure couldn’t change that. In other words, if each Indian (from India) were instantly vaporized by an outer-space alien after committing an egregious act of corruption (and they didn’t know this would happen) — the remaining Indian population would be lower corruption.

Over time, with only the non-corrupt Indians reproducing (because the corrupt ones were vaporized) — you’d end up with India having very low rates of corruption (they survived the alien corruption vaporization bottleneck).

Oppositely, if you only allowed the most corrupt Chinese to reproduce and sterilized all non-corrupt Chinese (honest, prosocial, high integrity) — you’d end up with Chinese that, on average, have high rates of corruption.

From an evolutionary perspective, corruption may have been culled in some ethnic groups and/or nations via socially accepted policies (death penalties)… in other cases, this may have been an indirect effect of random selection pressures (e.g. higher IQs survived cold winters with more cooperation and less corruption or something).

But anyways… this explains why some countries are more corrupt. It’s just how evolution shaped different ethnic groups.

And now with significant “globalism” which started ~500 years ago — we continue to observe disparities in corruption rates between distinct ethnic groups within the same countries (e.g. Chinese Singaporeans are far less corrupt, on average, than Malay Singaporeans).

So you may say Well, hold up, the Japanese were historically really violent… and now they are no longer violent.

The reality? Japan had periods of significant violence (e.g. 1467-1603)… but then during the Edo Period (1603-1868) many criminals were executed (eradicating corrupt DNA)… and after other selective pressures, we now have lower corruption traits in DNA in Japanese in 2025.

My note: From an evolutionary perspective “higher corruption” downstream of genetics isn’t “good” or “bad.” It just “is.” You assigning “good” or “bad” to it is the problem. Obviously it’s not a desired trait in cooperative societies like we currently have… but it may have been evolutionarily adaptive under certain historical conditions (hence its prevalence); or may have never been selected against (for various reasons).

VIII. Strategies to Eradicate Corruption in 2025

An effective way to reduce corruption would be to execute all adults found guilty of extreme corruption-related crimes. This would have a multi-pronged effect: (1) culls corrupt DNA from existence AND (2) incentivizes honesty/non-corruption.

You could also use the military to eliminate any corrupt officials… the problem here is that it’s like whack-a-mole… one out and another one enters (sometimes worse than the first).

Conditional foreign aid might work well… with some sort of Prisoner’s dilemma psychology (threaten to fund neighboring country instead of them if they don’t eradicate corruption).

I think perhaps the best strategy is to invent a cost-effective gene therapy (gene edits) for IQ upgrades in select countries. Identify a few genes that have outsized effects for improving intelligence/cognition (assuming safe) and incentivize people to get these “upgrades” with monetary rewards.

If we can get intelligence to at least ~90 it would be a massive improvement in corruption… and if we could get it higher (e.g. 100-105) a lot of corruption would likely vanish… but obviously not all because IQ is just one segment of the overlap.

We know intelligence is a byproduct of thousands of genes, but we could maybe edit some for a potentially outsized positive impact: BDNF, GRIN2B, COMT, FOXP2, CHRM2, etc. And the effect compounds (future generations are born with these variants).

Otherwise you could just try to leverage the corruption effectively to give your own country an edge. Cooperate with the corrupt for better long-term positioning (even if the “wokes” accuse you of “exploiting” others).

1. Zero-Tolerance Aid Policy (Extreme Conditional Aid)

Immediate halt of all non-emergency aid unless measurable, transparent anti-corruption improvements (based on CPI).

Clearly defined criteria; incremental aid restored only upon tangible progress.

Why Effective? Creates powerful domestic incentives due to intense economic and political pressure.

2. Personal Sanctions and Asset Freezing

Aggressive targeting of corrupt officials' personal and family finances.

Internationally freeze assets, revoke visas, ban travel, publicly blacklist corrupt leaders and their immediate circles.

Why Effective? Directly hits corrupt individuals personally, bypassing domestic protection.

3. Harsh Hardcore Law Enforcement (Zero-Tolerance Domestic Prosecution)

Rigorous domestic prosecution, lifelong imprisonment, labor camps, permanent forfeiture of wealth, immediate removal from office.

Visible public trials and humiliation.

Why Effective? Creates visceral fear, rapidly changing behaviors.

4. Reward Whistleblowers (Citizenship & Massive Financial Rewards)

Provide citizenship, permanent relocation, guaranteed security, and large financial incentives for whistleblowers exposing high-level corruption.

Why Effective? Massively increases risk of corruption exposure and internal paranoia.

5. Death Penalty for Extreme Corruption (Military Strikes)

Implement capital punishment for severe, high-level corruption (e.g., presidents, ministers, high-ranking judges, generals).

Why Effective? Extreme deterrence effect; sends strongest possible message.

6. Blacklist from International Banking and SWIFT System

Exclusion from global financial infrastructure for severely corrupt states.

Economic isolation to force drastic internal anti-corruption reform.

Why Effective? Catastrophic financial pressure forces urgent internal change, but careful due to potential humanitarian side-effects.

7. Impose Harsh Trade Penalties & Economic Isolation

Enforce severe trade tariffs, restrictions, embargoes to cripple economies of corrupt nations.

Why Effective? Generates intense internal economic pressure for reforms.

8. Foreign (Independent) Leadership & Oversight

Temporary transfer of government and administrative oversight to independent international or regional technocratic bodies.

Why Effective? Breaks existing corrupt power structures quickly; historically effective but faces sovereignty challenges.

9. Fund & Publicize Competitor (Neighboring) Countries

Redirect trade, investment, and diplomatic support to neighboring nations with lower corruption.

Explicitly market those countries as preferable alternatives.

Why Effective? Generates competitive pressure on corrupt regimes to reform quickly.

10. Establish Global Corruption Accountability Tribunal (like ICC)

International tribunal specialized in prosecuting cross-border corruption crimes.

Credible threats of international prosecution and imprisonment beyond corrupt officials' domestic protection.

Why Effective? Provides international accountability, although slow due to legal bureaucracy.

11. Incentivize & Promote Outbreeding (Reduce Nepotism Networks)

Economic and social incentives to break familial and nepotistic corruption networks.