Black People in TV Commercials, Interracial Couples, and Dumb White Guys - At Odds with U.S. Demographics: Woke Agenda or Smart Ad Strategy?

Why are there so many black people in U.S. TV commercials relative to their total population (~13%)?

Over the past few years, if you live in the U.S. (United States) and watch TV with any sort of regularity, you may have noticed (I think impossible NOT to notice) that every commercial (or every-other-commercial) pretty much features black people (i.e. African ethnicity).

What’s funny is that this specific cohort (blacks) often complains that they aren’t getting enough representation in TV/media (including commercials).

An interesting anecdote: I recall McDonald’s began including blacks more frequently in commercials… and then they complained heavily on social media that “McDonald’s is exploiting poor black communities” by targeting them with “junk food ads.” (Guardian, 2022)

You’re damned if you do… damned if you don’t, right? Include black people in junk food ads and you’re nefariously plotting to damage their health. Don’t include them? You’re discriminating for lack of inclusion.

I’ve mentioned to others that if you watched commercials on mute, you might assume the commercials were being broadcast from South Africa or Brazil (or somewhere else in Africa) — or you’d assume the U.S. population was at least 50% black people.

And that’s pretty much what many people in the U.S. actually think. A 2021 YouGov survey reported that Americans thought ~41% of the U.S. population was black (far higher than the reality of ~13%).

I’m far from the only person who’s noticed this trend… in fact, you’ve been living under a rock or just never watch TV if you haven’t noticed.

Has anyone else noticed that almost every single couple/family in commercials is now interracial? (The Straight Dope Message Board)

Why are 70% of the people in commercials these days, Black? (Quora)

Why so many blacks in ads? (The Rational Pessimist)

When advertisers fetishize race (Washington Times)

The rise of hyper-tokenism & TV ads: why whites and straights are out (Spiked)

Advertisers are trying too hard to demonstrate diversity by shoehorning minorities (DailyMail.co.uk)

Some have gone on to conduct their own investigations to determine levels of racial representation in commercials for mainstream events.

A Reddit user recorded the race of all 433 actors in the 2022 Super Bowl commercials. He used Excel, Tableau, a notepad, and pencil — and it included Knoxville, TN regional commercials (which likely inflated the rate of white actors, according to him).

As you can see from this analysis, black representation in advertising was nearly ~40% in the Super Bowl. This is ~27% more than actual U.S. population, but this makes some sense when considering that the NFL is over 50% black players. (Statista, NFL Racial Diversity, 2023)

Most advertisers feature current and/or former NFL players (many of whom happen to be black). So I’m not sure that this is necessarily an optimal way to track the degree to which blacks are overrepresented in advertising.

Many nonwhites, including: blacks, hispanics, and asians agree that the racial groups and pairings in TV commercials in the U.S. seem at odds with reality — and some dislike it, some don’t mind it (neutral), and others prefer it.

The shift in TV commercial ad demographics (featuring more black people) over the past ~10 years was prompted by a convergence of factors, including:

Surge in DEI initiatives, think-tanks & legal requirements

“Woke” acceleration under Biden/Harris

George Floyd & BLM movement

Woke mind virus liberals/progressives in high-ranking TV/media positions

This combination led ultra-progressive and/or liberal individuals within the TV/film industry to take the entire advertising segment and put it in a vise-grip-chokehold with an optimal woke fantasy of racial demographics.

To be clear: I have zero issue with black people being in TV commercials or media advertisements.

However, many think it’s bizarre or a bit mentally jarring to see inorganic “forced” diversity to the extent that people are laughing at how many black commercials there are in a row on TV in America. (U.S. TV but Africa demographic commercials)

As a good-faith researcher, I’ve compiled some logical reasons more blacks are in TV commercials than ever before in 2025.

1.) Blacks care more vs. other races

Black people care more about representation (seeing others like themselves) in TV ads/commercials than other racial groups.

Thus it makes logical sense to have a disproportionately higher number of blacks in TV commercials than other groups — because purchasing of products for other groups remains the same but increases for blacks — so ultimately you get a net positive ROI.

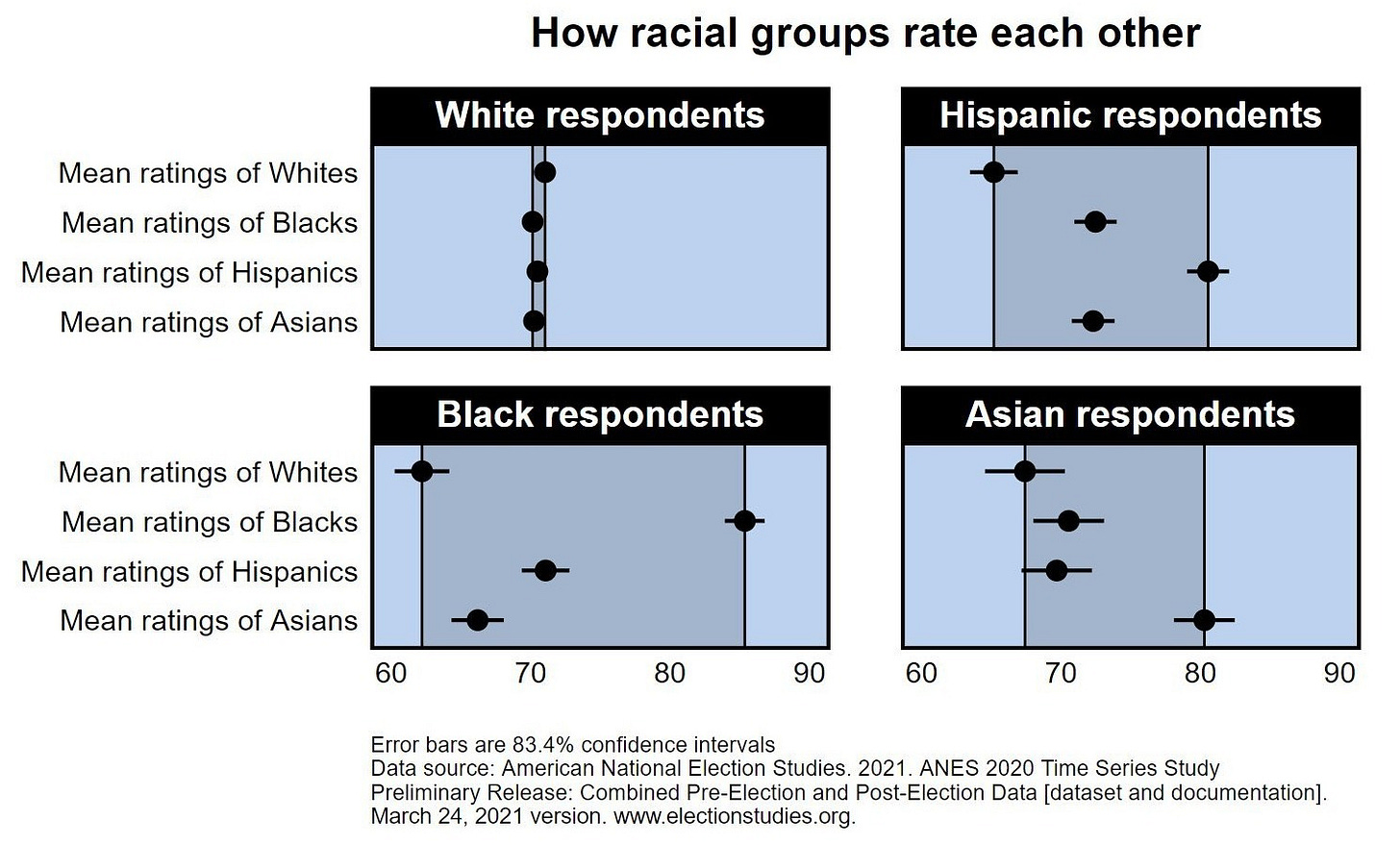

In fact, a report noted that White Americans’ preference for Black people in advertising has increased. Whites are preferring Blacks as endorsers over fellow Whites — whereas Blacks still prefer other Blacks. (Lenk et al., 2024)

From the Lenk et al. study, some might argue that whites are mostly indifferent to blacks — whereas blacks strongly favor blacks… this is a valid interpretation as well.

Earlier research by Bragg et al. found something similar (in targeted food & beverage commercials) noting: “both Black and White adolescents reported more positive affective responses to ads that featured Blacks compared to ads that featured Whites.” (Bragg et al., 2019)

2.) The “cool” factor

It is true that black people are heavily involved in influencing U.S. culture — music (e.g. hip-hop/rap, R&B, etc.), dance, niche comedy, sports/athleticism, etc.

By including black people in TV ads, some argue that you get a “cool” factor that may increase purchases of products that you wouldn’t otherwise have gotten.

3.) Watching more TV

Some other reasons I’ve heard: More black people watch TV per capita and desire TV/content that represents them more than other groups.

As a result, companies advertising on TV may cater to blacks a bit more than other racial groups.

Note: I question the legitimacy of this claim, as the research itself was conducted by “Nielsen’s Diverse Intelligence Series” (Nielsen, 2024). And even if true, black people are only ~13% of the total U.S. population. So even if they’re watching more TV per capita, absolute watch hours can’t beat other racial groups.

4.) Overcompensation & DEI/woke initiatives

It’s possible that the surge in commercials featuring black people is related to things like George Floyd, BLM, DEI initiatives, and woke legal requirements put forth under Joe Biden & Kamala Harris.

I know there were a lot of requirements made of large companies (many of whom do a lot of advertising) and some of this may have led them to err on the side of safety (better to go overboard than too light).

Also possible that companies realized they may have been historically too light on black representation — and are now overcompensating (pendulum type effect).

Another interesting nuance to many commercials is they often fit the exact type of woke you’d expect: black guy is always law-abiding and reasonable or smart, white guy always criminal or dumbass.

I understand the sensitivity here and know that it’s generally acceptable to poke fun at white guys (most don’t care).

This is also common in modern sitcoms (frequently has a fairly smart woman, etc. and a borderline retarded white dude).

Asking questions about why there are so many blacks in TV commercials now gets you labeled racist or sexist (even if you’re a black person, and even if you’re neither of those things… some are genuinely just curious!)

Funny enough even the highly-polarized left-wing brain-rot social forum that is Reddit has these types of questions being asked in good faith by left-wingers. Most replies are too bad faith and give the standard woke mind virus reply: Are you racist? Why do you care? Nothing good faith here.

To satisfy my curiosity, I researched why commercials are going full throttle with blacks in the U.S. in 2025 — and other racial groups like Hispanics (~20% of U.S. population) and Asians (~7.2% of U.S. population) remain mostly nonexistent from TV commercials & media ads relative to their % of the population.

There is a reasonable amount of formal research on advertising reactions — but take the findings with a massive grain of salt… because most of the research is done by DEI teams and/or woke researchers. Consider the specific methods, limitations, omissions, potential agendas, and backgrounds of the researchers.

Note: Many ad agencies conduct their own “in-house” research/analyses and don’t even share any methods — so be skeptical until more transparency is shown. After these weak studies they go on a PR rampage about why diversity in ads is better. (It may actually be better, but would be nice to verify.)

I.) TV Commercial Diversity Timeline in U.S.

2000s: Underrepresentation & Slow Change

In the early 2000s, TV commercials in the U.S. were still dominated by white actors, with minorities appearing only sparingly.

Content analyses around that time showed that Hispanics were virtually invisible – one study found they appeared in <1% of prime-time TV ads. (Li-Vollmer, 2009)

Black actors were more common than other minorities but still underrepresented relative to their ~12% share of the U.S. population.

These few appearances often relegated minorities to background or token roles. Advertisers largely played it safe with casting, reflecting the era’s less diverse marketing norms and a belief that the “general audience” was white.

Overall, the 2000s saw only gradual progress, with ads rarely or infrequently mirroring America’s actual racial mix.

2010–2015: Intentional Inclusion Begins

By the 2010s, calls for diversity and inclusion began influencing advertising. Brands started to proactively cast Black actors and other people of color in mainstream commercials, not just in niche marketing.

A pivotal moment was the 2013 Cheerios ad featuring a Black father, white mother, and their biracial daughter – one of the first high-profile interracial family depictions in a major U.S. brand commercial. (VOA, 2021)

The ad sparked an outpouring of racist backlash online, but Cheerios’ parent company stood by it, and the strong support from other viewers marked a turning point.

This incident demonstrated both the risks and rewards of diverse representation: it courted controversy from some, but also earned praise, reflecting shifting public expectations.

Following this, more brands felt emboldened to feature interracial casts and non-white leads.

Industry research was also signaling that diversity sells with many researchers claiming that ads with mixed-race/interracial couples capture more consumer attention (even if they still draw negative reactions from biased audiences).

2015–2019: Diversity Outpacing Demographics

In the late 2010s, diversity in commercials accelerated, driven by social movements and corporate diversity pledges.

By 2018, Black representation in U.S. advertising was reaching or exceeding parity with population share.

Individuals reporting on social media sites tracking representation on their own over limited commercial blocks noted that Blacks appeared in ~40% of TV ads in 2019. This means they noted Blacks in nearly half of all commercials they had watched.

In the U.K., a similar trend was noted: Black Brits (about 3% of the population) jumped from 5.7% of ad characters in 2015 to 13.3% in 2018 (AdAssoc, 2021).

In other words, Black people were suddenly overrepresented in ads – an intentional over-correction by advertisers aiming to appear inclusive. Advertisers also began routinely including at least one person of color in ensemble commercials.

In 2017, the blogger “Rational Pessimist” noted that blacks in ads were “way overrepresented” relative to their 13% population share, observing even a 2-person ad (e.g. a retail ad showing two Black women) had become unremarkable. (RationalPessimist, 2017)

The same blogger theorized this reflects how advertisers target younger, more diverse audiences: “black faces” in ads lend “coolness, hipness” and signal a brand’s progressive values, appealing to affluent millennial consumers.

Meanwhile, older or more conservative white viewers – who might prefer traditional all-white casts – were “just disregarded” as they’re not the desired demographic.

Post-2020: A Diversity Push & Corrections

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests marked a watershed for corporate America’s focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Major brands issued statements and vowed to increase minority representation in their marketing.

This was immediately reflected in ads: researchers found a “positive time trend” starting mid-2020 where advertisers continuously increased the share of Black models in digital ads.

Many companies felt pressure to show solidarity and avoid appearing “out of touch.” As a result, late 2020 and 2021 had record racial diversity in commercials.

A study of over 1 million video ads by Extreme Reach noted portrayals of Black people jumped from 12.3% of ad appearances in 2019 to 16.5% in 2021, and Hispanic representation rose from 6.2% to 9.6%. (Extreme Reach, 2022)

For context, Black and Hispanic Americans are about 12.7% (Black) and 19.8% (Hispanic) of the U.S. population, respectively.

Asians hovered near parity (around 8% in ads vs ~6–7% of population).

In the U.K., a 2023 analysis similarly found Black people (under 3% of Brits) appeared in 37% of British commercials.

This deliberate diversification was driven by DEI commitments and the belief that “advertising can be a powerful force for social good”, as one industry report put it. (AdAssoc, 2021)

Notably, this wave of inclusivity was not sustained uniformly. By 2022, some backtracking occurred as “diversity in video advertising receded” from its 2020–21 peak.

That same large-scale analysis found white actors’ share rebounded to ~73% in 2022 from 66% in 2021, and portrayals of Black and Hispanic people shrank (Black fell to 14.3% of ad appearances in 2022 from 16.5%, and Hispanic plummeted to 5% – a four-year low). (MarketingDrive, 2022)

So they allege that, after the initial post-2020 spike, 2022 commercials became “whiter” again. Industry observers suggest this dip may indicate that some DEI pledges were more about 2020’s publicity than permanent change.

Economic pressures also played a role – facing budget cuts in 2022, many marketers reverted to “business as usual,” which often meant the default casting of white actors. (I suspect it was just reversion back to common sense… remember the U.S. is still mostly white!) (U.S. Census, 2024)

Still, even after this pullback, representation levels of Black actors in 2022 remained higher than pre-2020 norms.

I suspect that if you studied mainstream TV in 2025, you’d note that racial diversity and black representation in commercials/ads on major networks (ABC, CBS, ESPN, NBC, TNT, FOX) remains high. On certain channels e.g. ABC & ESPN, I’d guess it’s nearly 50% of commercials given the NBA/NFL focus.

By early 2025, diversity in commercials remains a work in progress: the overall trend since 2000 has been a stark increase in non-white visibility, with Black representation rising the most dramatically.

Yet these gains are uneven – Hispanic and Asian people continue to be under-cast, and diversity can ebb when not vigilantly prioritized.

Turning points in 2000–2025: The late 2000s saw modest inclusion efforts; early-to-mid 2010s brought bold moves like the Cheerios interracial family ad, reflecting growing acceptance (and debate) of diversity.

Late 2010s (around 2015–2018) marked the period when ads visibly “caught up” to – and even overshot – demographic reality for Black representation, driven by conscious inclusion campaigns (the U.K.’s Lloyds Bank even launched reports to track and champion ad diversity).

The 2020 BLM movement was a catalyst for an unprecedented surge of diversity in ads across Western markets, as companies scrambled to signal their values.

And by the mid-2020s, the industry has been calibrating those efforts – trying to maintain authentic inclusion amid some backlash, budget pressures, and the recognition that mere token diversity is not enough.

International Analysis: U.K. & Australia

The United States (U.S.) and United Kingdom (U.K.) have largely led the shift towards more racially diverse TV commercials/ads.

In the U.S., blacks are clearly now in far more than 13% of mainstream TV commercials (I’d guess 20-50% depending on the network) and in the U.K. they are in over 30% of commercials by some estimates (despite being under 3% of the population).

The U.K. has an untreatable case of the woke mind virus… so much so that they are forcing racial diversity for a race that is barely in their country… this is pure comedy. Imagine if Nigeria suddenly felt compelled to put whites in 1 in 3 TV commercials. People would be like WTF.

The U.K. had overrepresented blacks in TV commercials & ads for almost 2 decades… they beat everyone to to the punch, including the U.S.

A report from as early as 2006 noted “black people are actually over-represented in UK television advertisements.” (Sudbury & Wilberforce, 2006)

The DailyMail published an article stating “Advertisers are ‘trying too hard’ to demonstrate diversity by shoehorning in minorities, study finds.” (Gordon, 2019)

It’s not just in UK TV adverts though… it’s also in TV shows. This has led some to write about the rise of “hyper-tokenism.” (West, 2023)

As one commentator put it: “If you were to watch ads in the UK you would think most people in the UK are Black. Nearly every ad you watch contains a black person.” (Bishop, 2023)

According to the Advertising Association of the U.K. which tracked “black representation in marketing”… black representation in ads increased to 13.3% in 2018 (in the UK) from 5.7% in 2015. (AdAssoc, 2021)

Quick reference: Black people make up just ~3.7% of the UK population. This means they are massively overrepresented vs. reality.

What about in Australia?

Online many woke nutjobs have taken to complaining about the lack of black people in Australian TV commercials and ads… but what these dolts don’t realize is that blacks are only ~1.3% of Australia’s population!

So implying that Australia is somehow behind the times with advertising is ridiculous… they don’t have the same demographics as the U.S. or the U.K.

So it makes logical sense that a 2017 study in Australia found 76% of TV ads there featured all-white casts, and only 5% of ads had no white actors at all. (AdNews, 2017)

In those Aussie ads, Asian faces appeared more often (8% of ads) than Black faces (5%) – aligning with Australia’s larger Asian-descent population.

Once again… this makes logical sense.

By the 2020s, Australian advertising began focusing more on multicultural and multiracial diversity (with initiatives urging more Indigenous and Asian representation), but the scale of change has been more modest compared to the U.S./U.K.

Racial demographics of Australia (2025)

White / European – 76%

East Asian – 6.5%

South Asian – 3.5%

Indigenous (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander) – 3.8%

Southeast Asian – 2.5%

Middle Eastern / North African (MENA) – 1.7%

Black / African – 1.3%

Other / Mixed Race – 2%

In short, Western countries share the trend of increasing diversity in ads, though the pace has varied – the U.S. and U.K. saw rapid shifts, while Australia and others are playing catch-up to better reflect their own multiethnic societies.

II.) Portrayal Patterns: Dumb Men, Dumb White Guys, Smart Women, Smart Minorities

Alongside racial representation, the sex dynamics and stereotypes in commercials have evolved significantly from 2000 to 2025.

A striking pattern that emerged (and intensified in the 2010s) is that white men are often cast as the bumbling fool, while women or Black characters play the voice of reason.

There’s even a Twitter/X account dedicated to this niche: “White Men Are Stupid in Commercials” (@StupidWhiteAds).

Many have noticed that “dumb men” or “dumb white men” is a common trend in TV commercials now. (Depicting men as stupid, morons, idiots, slow-witted, etc.)

The go-to ad joke is still the white male moron (Digiday, 2016)

Dumb men the latest punching bag in advertising (CBC, 2016)

Dumb dads: why are there so many male bashing commercials? (CanTechLetter, 2017)

Dumb white people in TV commercials (Reddit, 2022)

This trope – sometimes called the “dumb dad” or “doofus husband” stereotype – became extremely common in advertising.

For example, countless household product commercials would depict a clueless husband making a mess, only for his competent wife to roll her eyes and fix the situation (usually with the advertised product).

Many have lampooned these “male-bashing commercials,” citing an insurance ad that literally refused to insure men because they’re “stupid enough to drive their car over a cliff,” and a detergent ad implying guys “don’t know how to wash dishes”.

Such portrayals echo sitcom tropes dating back decades (e.g. Homer Simpson as the lovable idiot), but advertising took it to new extremes, often for comedic effect.

By the mid-2010s, advertisers seemingly assumed audiences (especially women) would find hapless men endearing or funny – and it often worked, but not without criticism.

Survey data confirms men noticed this trend. In one survey, 20% of men agreed that ads were too focused on portraying men as incompetent at household tasks, and 25% of men said they “find it hard to identify with men as they are portrayed in ads.” (Daubney, 2016)

A sizable minority of male viewers felt alienated or insulted by the constant depiction of their sex as inept. This led to discussions about misandry in media – a mirror to long-standing concerns about misogyny.

Media commentators pointed out the “role reversal” at play: increasingly, “men in adverts are prized for their looks, but ridiculed for their brains – precisely where women were in the 1950s and ’60s”, as one columnist noted.

The pendulum had swung. In the past women were stereotyped as scatterbrained or solely homemakers, now men (especially white husbands/dads) are the default buffoon.

Advertisers didn’t randomly stumble into this trope – there are underlying motivations. Women drive a majority of consumer purchases (estimates often say 70–80% of household buying decisions are influenced or made by women), so ads for cleaning supplies, food, insurance, etc., aim to resonate with her. (Oliver Wyman, 2019)

Showing a savvy woman who knows best (and a dopey man who needs her guidance) is a formula designed to flatter the target female consumer. It assures her that “you’re the smart one in the household – our product recognizes that.”

The male doofus device also avoids offending women viewers – unlike the bygone era where a pretty housewife needed a man’s help, now it’s the man who’s the punchline.

Additionally, ads have been careful to avoid negative stereotypes for minorities, which results in white males more often cast as the fall guy or even the villain.

For instance, it’s observed that commercials for home security systems virtually never cast Black men as the burglar – the intruder is almost always a white guy (to steer clear of reinforcing negative data that Blacks commit more crime per capita than any other racial group in the U.S.)

Thus, if a script calls for a “bad” or foolish character, casting directors may default to a white male as the “safe” option, politically speaking. Over time this has created its own cliché of the oafish white dude who is schooled by others.

Women and minorities, by contrast, are often portrayed as competent, wise, or morally upright in modern commercials – sometimes almost too flawless.

We frequently see the scenario of a patient wife, or a clever Black friend, or a no-nonsense Black mother, correcting the errant white guy with a knowing smile.

Likewise, ads increasingly feature women in professional, authoritative roles (doctors, bosses, problem-solvers), a deliberate correction to past eras where men were almost always the “expert” in ads.

In fact, research by Kantar found that in 2019 fewer than 1 in 10 U.K. ads featured an “authoritative female character,” despite evidence that “strong women hold greater sway over consumers.”

This insight has encouraged brands to feature more “strong women” protagonists, who come off as credible and intelligent – whether it’s a mom confidently choosing the right minivan, or a female IT professional explaining a tech product.

The prevalence of the dumb male/smart female trope eventually prompted regulatory attention in the U.K.

In 2019, the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) banned ads that include harmful gender stereotypes, including the very common portrayal of men as incompetent fathers or useless at domestic chores. (Reuters, 2019)

The first 2 ads banned under this rule were instructive:

One was a baby-care ad showing dads so distracted that they forgot their infants (playing on the idea that men can’t handle childcare).

Another was a car ad showing men exploring while a woman sat on a bench with a baby.

Both were deemed to “reinforce harmful stereotypes” and taken off the air. The ASA’s move signaled that what had become a lazy advertising trope was now viewed as socially damaging.

In essence, British authorities concluded that constantly portraying men as “bumbling man-children” (and women as the perpetual caretakers) was not only outdated but could limit how children conceive gender roles.

While the U.S. has no equivalent ad regulation, the discussion has crossed the Atlantic – advertisers everywhere have been encouraged to evolve beyond one-dimensional portrayals of any sex/gender.

By 2025, the portrayal gap is starting to narrow (especially outside the U.S.): men in commercials are still often used as comic relief, but we also see more respectful portrayals than a decade ago, partly under the influence of guidelines like the ASA’s.

There’s also a conscious effort to diversify who gets to be “the smart one” in ads – e.g. sometimes a Black woman might be the humorous bumbler (though advertisers tread carefully to avoid any racialized stereotype of incompetence).

Still, the shadow of the 2010s remains: it’s broadly acceptable in advertising to poke fun at white males in ways it wouldn’t be for other groups.

This reverse stereotype can itself be problematic if overdone. Advertisers are now challenged to find a balance between humor and fairness – ideally showing both men and women of all backgrounds in competent as well as comedic roles, without defaulting to any single group as the go-to butt of jokes.

III.) Interracial Couples in TV Commercials & Ads

One of the most visible representational trends of the last 20 years is the normalization of interracial couples in commercials.

In the 2000s, it was rare to see a mixed-race couple or family in a TV spot – if they appeared at all, it might be subtly (e.g. a group scene where a white man and Black woman stand near each other, leaving it ambiguous).

But heading into the 2010s and especially post-2013, brands started explicitly casting interracial families. This shift both reflected and attempted to further an image of a modern, inclusive society.

The 2013 Cheerios commercial I mentioned earlier was among the first of its kind: it featured a Black father, white mother, and their child in a home setting, directly depicting an interracial marriage.

The fact this ad caused such a stir (YouTube had to disable comments due to vitriol) shows how uncommon the imagery was at that time.

A RIT thesis concluded that racism and hate were the 2 most commonly selected themes among the negative reactions. (Alsous, 2016)

Yet, the strong supportive response from many consumers (“It’s about time ads look like real families!”) emboldened other marketers. Soon after, other major brands followed with their own mixed-family ads.

For example, State Farm ran an ad around 2016 with a Black man proposing to a white woman (or vice versa) – which again got some hateful comments on Twitter, but also praise.

Each instance demonstrated that representation can be polarizing, but it generates buzz and signals progressive values.

Companies determined that the positive brand image with tolerant consumers outweighs the risk of angering prejudiced viewers.

As a result, by the late 2010s interracial couples became commonplace in advertising.

It’s not unusual now to see a commercial for a car, insurance, bank, or household product where the couple is Black and white (or occasionally other ethnicity combinations).

In fact, some viewers have remarked that mixed couples seem over-represented relative to reality.

For instance, one Reddit discussion noted “so many ads lately” show a Black man and white woman together, even more than monoracial couples. (Reddit, 2024)

This isn’t just anecdotal: academic research indicates interracial pairings in ads have indeed been used disproportionately as a deliberate signaling of diversity.

A 2020 study by Erin Hackenmueller at the University of Alabama stated:

“This study performed a content analysis of 543 couples in television advertisements from 2019 for differences in representation and portrayal between interracial and intraracial relationships. All advertisements were taken from three different networks within one conglomerate. Findings suggest that interracial relationships are overrepresented.” (Hackenmueller, 2020)

This aligns with those who had armchair suspicions that interracial couples were far overrepresented relative to the general U.S. population. However, which combination appears most often is interesting.

One might assume ads always pair a Black man with a white woman (a frequently seen duo) but a content analysis by a marketing professor alleges that the opposite is more common (or at least was in 2018):

About 70% of interracial couples in commercials were a white man with a Black woman, even though in real U.S. demographics Black male–white female couples are more common. (VOA, 2021)

This suggests advertisers were intentionally showcasing the less common pairing, perhaps to double down on diversity messaging (a Black woman with a white man puts both a woman and a person of color in prominent roles, and might sidestep certain racial taboos).

Historically, American racism was especially hostile toward Black men with white women; by contrast, a white man with a Black woman might have been seen as slightly less provocatively breaking the “color line” to some audiences.

That may be one reason advertisers gravitated to the latter pairing initially. Regardless of pairing, the frequency of interracial relationships in ads far outstrips their frequency in society.

In the U.S., about 1 in 10 married couples are interracial (and among those, Black-white pairings are a subset). (Pew Research, 2017)

Yet by the 2020s, it feels like nearly every other commercial family is interracial and/or mixed race.

In the U.K., which has an even smaller non-white population, the phenomenon is similar – but some estimate that over 1 in 3 British ads feature mixed-race couples or families.

This clearly goes beyond mere realism; it is a statement. Advertisers are effectively modeling an ideal of racial harmony and inclusion.

As Larry Chiagouris, a marketing professor, put it: “It’s the brands wanting to let customers know they are listening to their diverse needs… and not wanting to be called out as oblivious to people of color.” (VOA, 2021)

Featuring an interracial couple in an ad is an immediate visual shorthand for “we’re an inclusive, forward-thinking company.”

The use of interracial couples has some nuanced effects: On one hand, it has been positively received by many, especially people in mixed families who finally see themselves represented.

A mother of a biracial child noted it “makes kids who look different feel represented” and that she wants her son to see families like his on TV.

It’s also drawn in consumers whose values align with diversity – people who “want to feel good about the company’s values,” not just the product.

Some research supports that, overall, ads with interracial couples enhanced brand favorability among audiences compared to identical ads with an all-white couple.

But there are complexities: while one study found that a mixed couple ad outperformed a white-only ad, it sometimes underperformed compared to an ad featuring an all-Black couple or other match.

Advertisers have navigated this by careful casting and tone – often making the interracial pair appear as “normal” and relatable as any other, to maximize acceptance.

Additionally, some research shows that ads with black-white couples elicited more negative emotions and less favorable attitudes towards the ad and toward the brand than comparable ads with same-race couples — and that negative reactions to interracial couples are unrelated to ones own race or sex. (Bhat et al., 2018)

An eye-tracking study that evaluated preferences toward monoracial (all same race) or multiracial (multiple race) advertisements reported:

“We found that both Swedish and American students exhibited higher preference in monoracial advertisements.” (Torngren et al., 2020)

A study published in 2024 by Davis et al. noted the following:

“Across six experiments (N = 4,956) and a field study on Facebook, interracial couples in marketing appeals enhance brand outcomes relative to monoracial dominant (i.e., White) couples, but decrease brand outcomes relative to monoracial nondominant (i.e., minority) couples.” (Davis et al., 2024)

We should also note that advertisers usually stick to Black/white pairings when showing interracial romance. Other combinations (e.g. white-Asian, white-Hispanic, Black-Asian, etc.) are seen less frequently in general-market TV commercials.

This may be because Black-white relations carry the most symbolic weight in Western cultures and thus send the clearest virtue/diversity signal.

It could also be a function of casting availability and demographic targeting. (That said, in places like California or New York, one does occasionally see an ad with, say, an Asian woman and white man as a couple – but it hasn’t become as iconic a trope as the Black/white duo).

There’s also a noted absence of Black couples in many mainstream ads: some critics point out that if a brand includes a Black person, they often make their partner white – which, unintentionally, might imply that showing two Black people in love is less “universal” or marketable.

A piece published on Roger Ebert’s media site called: “Black Out: The Disappearance of Black Couples in Advertising” argued that monoracial black couples are no longer featured in TV commercials & ads — and have been replaced by ambiguous interracial couples. (Ponder, 2024)

So clearly not everyone is happy with representation when it’s clearly a forced artificial representation of reality.

My interpretation? It’s just ad efficiency, not anything deep. Check all the boxes: male, female, black, white, etc.

Interracial couples in commercials went from taboo to trendsetting between 2000 and 2025. The Cheerios ad was a flashpoint that opened the floodgates.

Now, it is often expected – even conspicuous – for big brands to include at least one ad depicting an interracial family in each campaign cycle.

This representational choice is partly driven by genuine inclusion efforts and partly by a desire to project a certain brand ethos.

While largely celebrated as progress, it’s not without detractors (a small but vocal segment of consumers continues to express outrage or discomfort at these portrayals, as evidenced by social media comments and even organized online complaints).

Brands, however, have largely decided that embracing diversity is the future, and that showcasing interracial harmony aligns with both their values and their business interests.

IV.) What’s Driving TV Commercial Actor Demographic Trends in the U.S.?

The shifts in representation described above did not happen by accident – underlying motivations and pressures have guided advertisers’ choices.

1. DEI Initiatives & Industry Pledges

The 2010s and 2020s saw companies across industries adopt formal Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) goals. In advertising, this translated to explicit targets for on-screen representation.

Some of this may have been a byproduct of Joe Biden signing an executive order “Advancing Equity and Racial Justice through the Federal Government.” (White House: Executive Order 13985)

The SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) under Gary Gensler announced a “DEIA” (Diversity Equity Inclusion Accessibility) plan in 2023. (U.S. SEC PR, 2023)

To avoid being on the wrong side of Biden’s governance and the SEC, many companies went overboard with diversity (nonwhite good, white ok/bad, nonwhite women good, women > men, etc.).

After 2020 many brands and ad agencies pledged to “cast at least X% people of color” in commercials or ensure every ad has a diverse mix.

Industry groups like the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) also launched programs to improve portrayals of women (#SeeHer) and minorities.

In the U.K., the BRiM (Black Representation in Marketing) initiative was launched in 2021 to increase Black presence on- and off-camera.

Such efforts provided top-down impetus – brand managers were actively tracking the diversity in their ads, a stark change from earlier decades when it was rarely measured.

These initiatives were often a response to public pressure and a recognition that representation matters.

After George Floyd’s murder, this went into overdrive: companies felt a moral obligation (and PR opportunity) to showcase solidarity with Black communities by elevating Black representation in their messaging.

Internally, many companies also diversified their marketing teams (some as a result of forced DEI mandates), which led to more inclusive output (a homogeneous team might not think to cast diversely, whereas a diverse team often will).

2. Fear of Social Media Backlash (“Virtue Signaling”)

Hand-in-hand with genuine commitments is a cautionary motive: brands are eager to avoid public criticism for being insensitive or behind the times.

Social media can erupt if an advertisement is perceived as exclusionary or stereotypical. No company wants to be the next viral scandal because their commercial had a tone-deaf depiction (or lack of any diversity).

Thus, a form of preemptive self-censorship has set in – e.g. “We can’t cast all white people in this ad; we’ll get called out.” In many cases, this results in what some call “virtue signaling” – making a token show of diversity to signal progressive values, sometimes more for optics than substance.

For example, casting a same-sex or interracial couple in a high-profile ad can earn a brand praise for inclusivity, even if the company’s track record is mixed. Companies are aware of this symbolic capital.

The earlier-mentioned overrepresentation of Black actors in ads (far above their population share) is partly a result of this calculus: it looks good for a brand to be seen as championing Black inclusion.

As a Reddit observer cynically put it, “Fortune 500 companies are now run by DEI-ers… put there by BlackRock and...” (an allusion to investor pressure), implying that a corporate mandate is driving the surge in Black casting.

While that Reddit comment is hyperbolic, it captures the perception that diversity in ads is sometimes more about appeasing stakeholders than authentic portrayal.

Still, fear of backlash is a powerful motivator – few brands are willing to risk a campaign that could be labeled sexist or racist.

It’s arguably made advertisers overcorrect, erring on the side of extreme diversity and ultra-positive minority depictions, to immunize themselves from criticism.

3. Changing Consumer Demographics & Behavior

The makeup and media habits of the audience have shifted since 2000, and advertisers are following the money.

Who watches the most TV? Black Americans, for example, historically watch significantly more television on average.

Nielsen data from the 2010s showed Black Americans tuned in to ~213 hours of TV per month – over 50 hours more than whites, and more than double the TV time of Asians. (Nielsen, 2011)

Even today with streaming, Black viewership of live TV remains higher than other groups. (Statista: TV Viewership per Capita, U.S. 2009-2023)

This heavy TV consumption by Black audiences means commercials airing on broadcast/cable will hit Black viewers frequently.

Representing them on-screen is a logical way to connect; Black consumers are likely to respond better to ads where they feel seen.

Similarly, Hispanics represent a fast-growing consumer segment (with nearly 19% of the U.S. population).

Many Hispanics watch Spanish-language channels, but a large number also watch general English-language TV – yet historically they scarcely saw themselves in those general-market ads.

Advertisers belatedly realized they were leaving money on the table by ignoring such a huge market.

The purchasing power of minorities is significant – e.g. Black Americans command $1.6 trillion in spending power, and collectively minorities account for over 20% of U.S. consumer spending. (Forbes, 2023) (Mastro & Stern, 2003)

Brands risk “shortchanging Black shoppers at [their] peril,” as Forbes bluntly put it. Thus, inclusion is driven by a profit motive: appeal to those lucrative audiences.

Additionally, women (across all races) have increasingly become the focus of marketers, not just for stereotypical “feminine” products, but across categories – precisely because women are often the decision-makers.

Ads have evolved to speak to women’s perspectives accordingly, as noted earlier (less patronizing, more empowering).

4. Social Values of Younger Consumers (Gen-Z & Millenials)

Younger generations (Gen-Z & Millenials) tend to expect diversity and reward brands that are inclusive. They are also more diverse themselves.

The “Rational Pessimist” speculates that for yuppie, better-educated, younger consumers… blackness is actually attractive – connoting coolness and with-it-ness, and these consumers see an “America fully integrating blacks” as a positive ideal. (Rational Pessimist, 2017)

So featuring Black culture or faces can make a brand seem “hip” and aligned with modern social values.

Companies like Nike capitalized on this (e.g. a Nike ad with Colin Kaepernick was polarizing among older crowds but popular with young, diverse, woke consumers and Nike allegedly saw sales growth); I suspect sales were unrelated though.

This generational values shift means representation isn’t just a “nice to have” – it’s increasingly expected by younger/diverse consumers.

In 2020, ~55% of 18-34 year-olds claimed that racial diversity in advertising was important to them — and ~46% of 35-44 year-olds felt the same way. (Statista, Ad Diversity, 2020)

This was up from nearly half in 2020, indicating growing awareness. In response, companies explicitly “rode the trend” and kept increasing minority representation to meet these expectations.

If Brand A doesn’t, Brand B will – and potentially steal the culturally conscious customers. In essence, representation has become a competitive factor… a woke prisoner’s dilemma.

5. Research & ROI Evidence

Over the last two decades, a body of marketing research has emerged around representation, providing data that often supports the business case for diversity.

Multiple studies indicate diverse ads can outperform homogeneous ones.

A 2023 study from Columbia University to analyze ads found that those including Black models had higher click-through and engagement rates than all-white ads, on average. (Hartmann et al., 2023) The authors concluded that advertisers are “well advised to diversify” their ads, as consumer response to Black-inclusive advertising was increasingly positive over time.

Another study from Northeastern University noted that ads with consistent diversity (meaning diversity wasn’t just tokenistic, but naturally incorporated) were seen as more authentic and drove better brand perception. (Overgoor et al., 2023)

However, studies also warn of conditions: diversity can backfire if done clumsily. If consumers sense an ad is pandering or inauthentic, it can breed cynicism. Multiple studies support this.

For example, research from San Francisco State University found that while many respond well to mixed-race couples in ads, some viewers (perhaps sensing a “ploy”) register more negative feelings if they suspect the brand is just trying to appear woke. (SFSU.edu)

Likewise, the Hispanic Marketing Council reports that Hispanic consumers “see right through” superficial representation – if an ad throws in a Latino actor but doesn’t feel culturally genuine, it can actually turn off Hispanic viewers. (Hispanic Marketing Council, 2022)

These insights motivate brands to not only include diversity but do it meaningfully, e.g. consulting cultural experts or authentically depicting the context (language, family dynamics, etc.).

Brands have also been tracking sales and sentiment linked to their inclusive campaigns.

The results have often been positive: when P&G released ads attempting to highlight racial bias (e.g. “The Talk” and “The Look”) they garnered a lot of praise from woke retards, but also strengthened brand loyalty among Black consumers.

Most of what was said in the ads was a blatant misrepresentation of reality (e.g. black people have to work twice as hard as others for the same results in U.S.); patently false information.

On the flip side, brands have faced boycotts from those opposing “woke” advertising, but these rarely dent sales in the long run and can even boost a brand’s profile among supportive demographics.

The drive for increased and favorable representation in commercials stems from a mix of social pressure, target marketing, and evidence that it’s effective.

Companies are navigating a complex map of stakeholder demands: activists and some consumers demand inclusivity and fairness; investors and executives see the growth potential of diverse markets; and creative teams strive to reflect a changing world (or at least not get called out for failing to).

Often the simplest way to satisfy all is to “go big” on diversity – hence the sometimes conspicuous overrepresentation and virtuous portrayals we see.

V.) Impact & Reactions: Effects of Trends (Harmful, Helpful, Neutral)

The representational trends in advertising carry a variety of impacts on audiences and have sparked mixed reactions across different groups.

While the intention is to promote inclusion and positive images, some argue the results can be distorted or suboptimal.

1. Positive Effects & Reception

On the whole, increased diversity in commercials has been welcomed by many viewers, especially those in underrepresented groups. Seeing people of one’s own race or a family that looks like yours on national TV can be validating.

For Black Americans, who for decades were portrayed in ads (if at all) as athletes, rappers, or in subservient roles, it’s empowering to now be depicted as the affluent homeowner, the loving parent, or the clever protagonist selling everything from luxury cars to financial services.

The same goes for women, who increasingly see themselves as CEOs, engineers, or decisive consumers in ads – a far cry from the 1950s housewife archetype.

These shifts can inspire a sense of belonging and aspiration. Importantly, broader audiences have also adjusted; numerous studies indicate that most consumers today expect diversity and respond positively to it.

About 59% of people said they prefer to buy from brands that support diversity and inclusion. And as noted, roughly ~70% of consumers in 2021 said a brand’s diverse ads mattered to them. (Lloyds Banking Group, 2021)

These figures suggest that inclusive advertising is largely hitting its mark in terms of audience approval. It can also have subtle societal benefits:

Normalizing interracial families and women in leadership roles via repetitive exposure in ads can help reduce stereotypes and biases over time. In essence, commercials (which people see hundreds of times a week) are reinforcing the idea that this is normal, this is America.

For younger generations growing up seeing a Black female surgeon talk about toothpaste, or a gay biracial couple buying furniture, that diversity is simply the default – which is arguably a healthy, progressive mindset.

2. Corporate & Market Benefits

From a business standpoint, the representational shifts have often proven savvy. Brands that embraced diversity early gained praise and sometimes free publicity.

For example, when that Cheerios ad went viral, Cheerios garnered immense brand recognition and loyalty from interracial families and supporters of inclusion.

Companies that have consistently cast diverse actors (like Coca-Cola or Ikea in their family-oriented ads) are often perceived as “forward-thinking” or “caring,” which can translate into brand equity.

Internally, these efforts also boosted morale among employees from those communities. Additionally, market expansion has been a clear benefit – ads that speak to Black or Hispanic audiences in culturally resonant ways have helped brands tap into those markets.

Even overrepresentation of certain groups (like Black Americans) can be seen as brands courting a demographic with outsized cultural influence (Black consumers often set trends that other groups follow, especially in music, fashion, and slang).

So some degree of “over-indexing” on Black representation might be very calculated: Black culture is cool and mainstream, thus showing a Black family using your product could attract not just Black buyers but everyone who sees that family as cool.

There’s evidence this works – some research indicates that ads with diverse casts can create a perception that the brand itself is diverse and inclusive, which many consumers like.

And as mentioned, ads featuring interracial or diverse groups tend to perform better with diverse and open-minded segments than homogeneous ads.

So from a pure marketing performance view, many companies see more upside than downside in these trends.

3. Criticisms, Negative Reactions, Backlash

A portion of white viewers (commonly male) feel alienated by the current advertising landscape.

They observe that in many commercials, “the only person who looks foolish or evil is a white guy,” and they resent it. In comment sections and forums, you’ll find complaints that “straight white men are the only group you’re allowed to make fun of now.”

Some take it further, framing the ubiquity of non-white faces as an anti-white agenda – e.g. one angry commenter wrote that minorities are “way over-represented... It’s cultural Marxism being foisted upon [us] whether [we] like it or not”.

While that extreme view is not mainstream, it reflects a real frustration among certain demographics who feel their reality is no longer reflected at all.

Especially for older white viewers who grew up with ads only showing white families, the sudden flip can feel like premeditated erasure of whites in the name of woke.

Many of these individuals have boycotted “woke brands” and some claim they’ve completely cancelled cable to avoid seeing what they perceive as woke psychological brainwashing and propaganda to satisfy leftist ideals.

By and large, these reactions haven’t materially hurt most big brands – the discontented tend to be a minority, and often the consumers most upset (e.g. some far-right segments) aren’t the core target market for many advertisers anyway.

Nonetheless, it’s a public relations tightrope. Companies must weigh whether overt representation might provoke a backlash that outweighs the gains.

So far, the consensus for most large brands has been to proceed with diversity – essentially betting that society as a whole is moving in that direction, and those who strongly object will be left behind (or will grudgingly get used to it).

Public opinion continues to trend toward acceptance of diversity. But the backlash is a reminder that representation in media is not value-neutral; it’s inherently political in the current climate.

4. Concerns of Tokenism & Authenticity

Another critique comes from the very communities that diversity efforts aim to serve. Some minority viewers feel that what they’re seeing is pandering or surface-level inclusion rather than meaningful representation.

For instance, Hispanic Americans have for years voiced that when they do appear in English-language commercials, it’s often stereotypical (e.g. the Latino friend with a heavy accent for a punchline) or just a checkbox fill (a Hispanic actor placed in an ad with no cultural context).

If an ad features a Hispanic character solely to claim diversity but doesn’t bother with authenticity – say, using Spanish appropriately or depicting something relatable to Latino culture – many in the community see it as disingenuous.

Remember, the Hispanic Marketing Council study I referenced earlier reported that ~47% are concerned about brands’ sincerity in marketing and ~49% avoided purchasing from a brand because ads did not seem sincere. (Most feel underrepresented or misrepresented in ads and dislike the “forced” woke bullshit). (HMC, 2022)

Rather than building loyalty, such tokenism can ring hollow. Similarly, Black British respondents to the Lloyds ad survey felt that despite increased visibility, 34% felt inaccurately portrayed and many felt ads did not reflect their culture or fell back on old tropes.

One example is the frequent portrayal of “dancing Black people in ads” – a trope called out by a writer who noted that while inclusion is great, constantly showing Black folks dancing joyously (often to sell insurance or fast food) can become its own shallow stereotype.

Some are so beyond woke that they’ve written articles on Medium like: “Stop Putting Dancing Black People in Ads.” At this point, if you are worried about whether black people are dancing in ads, you should seek psychiatric help… it’s 2025.

The woke mind virus zombies are so far gone that they think that these commercials are negatively “informing our unconscious thoughts” (I can’t even make this shit up if I tried).

The same goes for always casting Black actors as the wise, virtuous figure – it might seem positive, but it can veer into “putting on a pedestal” rather than showing real, rounded characters.

Essentially, minority audiences want better representation, not just more. The current trends are a step forward quantitatively, but qualitatively there’s room to grow to avoid new stereotypes or token roles.

To me, this is beyond comical. And once again goes with the “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” scenario I discussed — and with the idea that “some people will never be satisfied.”

Put more black people in ads? No not that way. Do it this way. Well that way feels forced and people don’t like it. Well should we remove them? Do it my way instead. No your way makes them look artificial and unconvincing. (The debate goes full circle.)

Evidence suggests that “authenticity” and presenting a “slice-of-life” execution are important… so if people don’t find your commercial authentic (i.e. it feels forced) — they won’t like it. (Mai et al., 2022)

The most obvious thing advertisers should keep in mind: if you try to please everyone you will please no one.

5. Blatant Neglect of Hispanics & Asians

While advertisers focus on black-white diversity, other groups are left out in the cold. Hispanics are damn near ~20% of the population (probably more at this point, as I don’t really trust the census data with all the illegals in the country).

Clearly they don’t complain as much about it… “the squeaky wheel gets the grease” (usually black people are chirping more on social media). Asians also rarely complain about not being featured.

Asians have been cast a bit more frequently in tech or finance commercials (playing on a “smart” stereotype), but they remain underrepresented relative to their 6–7% of the U.S. populace.

There’s also a perception that when Asians are included, they’re often “ambiguously ethnic” models who could pass as mixed or just generically non-white, rather than distinctly Asian roles.

Hispanic Americans face a double-edged sword: they are a huge market, but outside of Spanish-language media, they see surprisingly few relatable depictions.

The aforementioned Reddit user’s Super Bowl analysis highlighted that Hispanics were widely underrepresented – a stark finding given their population share (~1 in 5 Americans).

Native Americans and Middle Eastern Americans are virtually never seen in mainstream commercials except in very specific campaigns… which makes sense given they’re under 2% of the U.S. population. (Not many people care.)

But, the gaps mean the current diversity push might be inadvertently creating a new hierarchy of visibility, where Black (and to an extent multiracial) faces dominate “diverse advertising,” potentially at the expense of Latino or Asians because they aren’t whining much.

And as I’ve mentioned already (in the opener), I suspect demographics on TV/movies and social media advertising/commercials — has led many to develop a distorted mental model of U.S. demographics (thinking that it’s nearly 50% black people — and not realizing there are a lot of hispanics).

6. Formation of New Stereotypes

As discussed, tropes like the dumb white dad or the virtuous Black hero are arguably stereotypes in their own right.

While they arose to counter old biases, if they become the only narrative, they can be limiting and divisive.

White men being constantly depicted as fools or villains could contribute to a cultural disrespect or dismissal of white men’s positive contributions (some scholars even talk of an emerging bias against men in media, or misandry, that rarely gets acknowledged).

The ASA’s ban in the U.K. on portrayals of men as inept caregivers was an attempt to prevent potential harm such as young boys internalizing that “men are inherently less capable.”

Also, making white males the default antagonist in ads (to avoid casting minorities negatively) has the side effect of telling white men that, in the story of progress, they are inherently the problem – which might fuel resentment.

A more truly inclusive approach might involve sometimes showing a Black thief or a female fool without playing into a broad negative stereotype – but that’s very tricky territory for advertisers, and most avoid it entirely.

Thus, the industry tends to play it safe with “only punch up (at white guys).” This strategy averts one kind of harm (offending protected groups) but could instill another (engendering cynicism or grievance in the only group left unprotected).

7. Perception of Agenda & Loss of Trust

Another risk is that some viewers across backgrounds might feel that ads are now too calculated or politicized, undermining trust.

When every single advertisement break presents a checklist of diversity (the famous “Benetton ads” effect with one of each), audiences can grow skeptical: is this sincere or just marketing?

If representation choices feel forced, it can take people out of the narrative and make them focus on the brand’s motives.

A viewer might roll their eyes and say, “Okay, they’re just trying to look woke,” rather than absorbing the actual product message.

In evaluating whether the trends are suboptimal or harmful, it often comes down to who you ask.

Most women and people of color would likely say the increased representation is a long-overdue correction that, despite imperfections, is far better than the exclusion or negative stereotypes of the past.

They might acknowledge some issues (like lack of Hispanics or formulaic interracial casting) but view those as challenges to address while still moving forward with inclusion.

Many white men, especially younger ones, actually support these trends too (since they largely reflect modern values), but some feel the scales have tipped to the point of unfairness or inaccuracy.

There’s probably a generational split – younger white males are more accustomed to diversity and may be less bothered, whereas older ones voice more frustration at being portrayed as incompetent or rarely seeing someone like them portrayed positively.

Advertisers and creatives themselves are in a continuous process of self-assessment: they ask whether they’re truly connecting with audiences or just checking boxes.

The smartest brands are now looking at intersectional representation (acknowledging people have multiple identities) and authentic storytelling that resonates with specific groups rather than broad-strokes tokenism.

For example, instead of just casting a Black actor, a brand might build a mini-campaign around a culturally relevant scenario for Black audiences – that tends to win genuine praise.

While there are some distorted elements in current representation trends (over-correction in some areas, neglect in others), it’s hard to say they are “harmful”.

They may annoy some and miss opportunities for depth, but by and large, the move toward diversity has been beneficial for inclusion.

Even critics often agree that the answer is not to revert to the 1950s, but to strive for better diversity – more nuanced, broader-reaching, and more proportional representation (e.g. include all communities in a fair way).

Advertisers are beginning to heed that: for instance, there are increasing calls to improve Hispanic representation, to cast more Asian leads (not just sidekicks), and to avoid making any one group look invariably goofy or saintly.

VI.) Why TV advertisers might over-index Black representation in commercials (2025)

Blacks have the most substantial reactions to lack of inclusion or misrepresentation of any racial cohort in the U.S. They’re most likely to make noise… and this causes brands to panic, and ultimately cave to demands.

1. Fear of Backlash & Avoiding PR Nightmares

Social Media Pressure: Marketing teams know that if they release a commercial perceived as insensitive (e.g., mocking Black people, sidelining women, or casting a Black actor as a criminal), there can be swift, very public blowback—Twitter storms, negative press, boycott campaigns, etc.

Safe Targets: As a result, White men have become the “safest” demographic to depict negatively (as oafs, idiots, or criminals) without risking major accusations of racism or sexism. In other words, advertisers rarely get pilloried for making the White guy look bad.

Overcorrection: This leads to an overcorrection: Black or female characters are typically shown in a favorable, moral, or competent light, ensuring no one can claim the brand is perpetuating negative stereotypes of protected groups.

Advertisers are trying to dodge controversy. It’s less about lofty moral objectives than mitigating risk of being publicly labeled “racist” or “sexist.” White men end up the universal “punching bag” because they carry the least PR danger.

2. Appeasing Vocal Audiences & Activist Groups

Highly Organized Advocacy: In the U.S. especially, there is significant activism and media scrutiny around Black representation. If a brand looks tone-deaf or fails to feature enough Black faces, activists may call it out.

Threat of Boycotts: Certain groups (like NAACP or grassroots social media movements) can mobilize quickly against brands, something we rarely see if Asians or Hispanics are left out. The fear of such backlash drives advertisers to “overrepresent” Black consumers in proportion to their actual population share.

Less Organized Critique for Other Groups: Asians and Hispanics do not (in many cases) have the same level of well-known, unified advocacy or as much mainstream media coverage for underrepresentation. Thus, brands don’t feel the same heat.

A brand would much rather face a mild complaint from a small fraction of White men than endure a full-scale public relations fiasco spurred by well-networked activists who can make “lack of diversity” trend on Twitter.

3. Chasing the Black Consumer Market (and “Cool Factor”)

Higher TV Consumption: Research has long shown Black households watch more live TV on average than other demographics. If you’re running national TV ads, that’s a prime audience.

Cultural Influence: From music to fashion, Black culture often sets trends across American pop culture. Attaching your brand to that “cool” or “urban” vibe can help it resonate beyond just Black viewers—many young White consumers also gravitate to brands that feel culturally progressive or “hip.”

Spending Power: Black consumers’ spending power in the U.S. is substantial (over a trillion dollars). Advertisers often bet that prominently featuring Black individuals will both attract Black consumers and signal to younger, liberal-minded Whites that the brand is “with it.”

Putting more Black representation in commercials may yield a strong ROI—both financially (by appealing to heavy TV-watchers) and in image (“coolness by association”).

4. No Benefit with Asians & Hispanics

Language Segmentation: Many Hispanic viewers watch Spanish-language channels (Telemundo, Univision) that have separate ad markets. Advertisers can target them “over there,” so they don’t feel the same pressure to represent Hispanics in mainstream English-language ads.

Lower Perceived Risk: There is less immediate social-media blowback for excluding Asians or Hispanics. If a brand’s general-market ad has zero Asians, they rarely face a PR firestorm. So there’s no strong negative incentive forcing them to include these groups.

Stereotypes and Complexity: The “Asian” label encompasses many subgroups with different languages/cultures, so marketing teams are unsure how to do “inclusive” casting that actually resonates. They may see more straightforward payback by focusing on Black–White diversity.

Asians and Hispanics often get sidelined in mainstream commercials because advertisers don’t fear significant penalties for excluding them, and they can theoretically reach Hispanics via separate Spanish-language campaigns. So those groups stay underrepresented.

5. Interracial Couples as a Virtue Signal

Instant Inclusivity Badge: Featuring a mixed-race couple—especially a Black person paired with a White person—instantly telegraphs that a brand is progressive. It’s a quick visual shorthand for “look how inclusive we are.”

Disproportion vs. Reality: Actual Black–White marriages are a small share of total U.S. marriages, yet ads make it look like half the country is in a mixed relationship. That’s not by accident; it’s purposeful overrepresentation for brand image.

Choice of Pairing: Often it’s a White woman with a Black man (or a White man with a Black woman) because that pairing sends the strongest “racial harmony” message—and in the U.S., Black–White race relations are the most scrutinized dimension of diversity.

By showing interracial couples far more than they statistically exist, advertisers loudly broadcast their alignment with “modern values,” hoping to attract younger or socially liberal consumers and avoid charges of being out-of-touch.

6. The “Dumb White Guy” Trope & Power Asymmetry

Comedy Without Consequence: Making a White male the butt of the joke is the safest move. It doesn’t trigger claims of racism, sexism, or other “-isms.” It’s the comedic path of least resistance.

Flipping Old Tropes: Historically, ads often portrayed women or minorities in subservient, silly roles. Now advertisers invert that dynamic, presumably to show how “far we’ve come.”

No Organized Pushback: There isn’t a large-scale movement scolding companies for insulting White men. A few individuals might gripe, but there’s no systematic threat—no major brand is going to get canceled for White male bashing.

“White male as dummy” is a formula that entertains target demographics (often women) while sidestepping accusations of prejudice. It’s effectively the only comedic punching bag left that won’t spark mainstream outrage.

7. Corporate Strategy: It’s Mostly About Risk Management & Profit

Despite all the surface talk about “values” and “social responsibility,” behind closed doors:

ROI Drives Decisions: Marketing budgets flow to whatever the company believes will maximize sales or brand goodwill. If executives believe (a) featuring a diverse or interracial cast can expand their market and (b) it immunizes them from scandal, that’s where they’ll invest.

Check-the-Box DEI: Many large companies have internal diversity quotas. Agencies are told “every ad must have at least one Black actor,” etc., to meet those corporate KPIs. Genuine or not, it’s the new business norm.

Defensibility: If questioned about “why so many Black faces vs. 13% population,” a brand can simply say, “We’re celebrating diversity,” which is nearly impossible to attack without looking bigoted. Meanwhile, they face no penalty for ignoring Asians or Hispanics to the same degree—those groups often lack mainstream media sympathy on underrepresentation.

It’s a bottom-line calculation. Overrepresenting certain groups or depicting White males as doofuses is a low-risk, high-reward marketing move given the cultural climate.

8. Potential Downsides & Backlash

Alienation of some white viewers: Certain White audiences feel annoyed or resentful that they’re cast as idiots or criminals in virtually every commercial, or that they see an overwhelmingly non-White cast in an 80%-White country. While their complaints rarely become a PR crisis, the frustration can degrade trust or brand loyalty in the long run.

Tokenism & Shallow Representation: The push for “diverse faces” can lead to simplistic or pandering portrayals—Black people always shown as wise and moral, interracial couples depicted as an ideal, etc., which can ring hollow or unrealistic.

Ignored Segments: Asians and Hispanics may feel perpetually invisible in mainstream advertising, potentially forming a separate kind of distrust or cynicism toward brands that claim inclusivity but really just show Black–White diversity.

Over-saturation: When every brand floods the airwaves with nearly identical diversity checklists (the “rainbow lineup” in every ad), viewers might tune out the intended message. Some see it as contrived virtue signaling and stop taking it seriously.

9. Historical Arc (2000–2025) in Brief

Early 2000s: Predominantly White casts, occasional Black secondary roles, very few interracial couples.

2010–2013: First intentional pushes for inclusion. Cheerios’ mixed-race family ad stirs controversy but gets massive publicity.

Mid-2010s: Advertisers realize the marketing upside of diversity. “Dumb White husband” trope proliferates for comedic relief, avoiding “off-limits” targets (women, minorities).

Late 2010s–2020: Black representation skyrockets, often surpassing actual U.S. demographics. Increased emphasis on interracial romance/families.

2020–2021: George Floyd protests + corporate DEI pledges lead to a surge in Black-focused advertising, even more “woke” or moral-driven campaigns.

2022–2025: Some slight pullback, but the overarching norm remains: never show minorities negatively, maintain overrepresentation of Black actors, keep White men as comedic scapegoats or mild antagonists.

10. Is It “Suboptimal” or Inevitable?

Whether this is “harmful” or just the new normal depends on perspective:

Brands: It’s largely beneficial—keeps them out of scandal, appeals to multiple consumer bases, signals modernity.

Underrepresented Groups: Black audiences may appreciate positive visibility; Asians/Hispanics often still feel overlooked.

White Men: Some are indifferent, others feel demonized or erased. But since they aren’t a potent boycotting force, advertisers see minimal downside.

Society at Large: Might get an inflated sense of how many mixed-race relationships exist, or how incompetent White men are. But consumer culture has always been more about aspirational illusions than strict realism.

The “over-the-top” representation of Black people and the “buffoonish” portrayal of White men isn’t purely about moral progress or “woke” ideology. It’s about risk management, harnessing cultural cachet, and appealing to the demographics who are perceived to matter most—whether due to social pressure or direct purchasing power. Advertisers believe these strategies maximize profit and minimize blowback in today’s climate. Until the cultural or economic incentives change, expect such trends to remain.

My thoughts re: black people & diversity in TV commercials…

I have no issue with black people, interracial couples, etc. in commercials in 2025… but what I’m seeing on some mainstream cable TV channels is far detached from U.S. demographic realities.

I should reiterate that I have NOT deeply examined each study on the effect of diversity in TV commercials or ads within the U.S. to determine all limitations, flaws, biases, etc. I suspect that a lot of the research is probably junk, but I hope it’s not. (A lot of the studies are done by DEI groups… they have an agenda to show: DEI good, old models bad.)

I also think that most “arguments” in favor of putting more: black people, interracial & mixed race couples, stupid white guys, etc. on TV commercials/ads are downright brutal.

Yes, it’s true that blacks are watching more TV per capita — but absolute TV watching (total eyeballs) is still far higher among non-black cohorts in the U.S.

And while blacks do have considerable purchasing power in the U.S. — it pales in comparison to most other racial groups. So the “purchasing power” argument makes little sense.

In 2025 I’m desensitized to diversity on TV commercials/ads. Today I watched FOX or ABC for a bit and counted Black people vs. White people vs. other races in the ~3-4 hours of TV that I watched… and it seemed as though black people dominated other racial groups in overall numbers. Maybe I should do my own investigation?

In some commercials I noticed that both “white people” and “black people” were present, but black people were more frequently the “main characters” (leads) and/or significantly outnumbered the whites (in commercials with many people).

In these cases, some studies may tally these commercials as having 50/50 representation (because they have some blacks and whites) but the magnitude of intra-commercial (within the same commercial) can sometimes skew heavy towards blacks; this may not show up in the research.

In my brief viewing time, I saw a few commercials featuring Hispanics… one of them had a guy that looked Hispanic as the lead (I think it was an Apple commercial). A few commercials had random Asians thrown in for good measure, but they weren’t usually the leads.

I get it… companies want efficiency: throw in 1 black minimum, add a white (dominant racial group of U.S.), and we’re good. If we feel extra spicy we could pad our diversity stats with a hispanic or asian. Ensure at least 1 man and 1 woman unless product is targeting men.

I also want to emphasize that emerging data imply that, for whatever reason(s), younger generation whites either: prefer OR are indifferent to black endorsers in commercials/ads whereas blacks strongly prefer other blacks. Assuming these data are accurate (not some BS research), it makes logical sense to add more blacks in commercials — as purchasing behaviors are thought to increase for blacks and stay the same for whites.

I think most Hispanics are indifferent about “inclusion” in commercials/ads. Maybe it’s because most of them consume Spanish media (ESPN Deportes, Telemundo, etc.) and/or many don’t know much English (illegals)… so advertisers can target them more effectively on Spanish media.

In retrospect, there was a clear snowball effect (started in the 2010s and probably peaked in the 2020s) in which racial diversity — especially black people — went from being less common to extreme dominance (most dominant of any group per capita). I think the snowball of diversity/black has peaked — but will stay large going forward.

Most normal people would agree that if you just quick viewed the TV commercials and/or ads muted, you’d likely think that this is straight out of Africa.

If you still think blacks are underrepresented on TV commercials/ads in 2025 within the U.S. — you should remind yourself that they are only ~13% of the U.S. population (not 40% as many Americans incorrectly believe). If you still believe this? You may be racist or heavily biased in favor of blacks (for whatever reason).

We have gone from historical underrepresentation to historical overrepresentation with “fast takeoff.” Since blacks clamor more than any other racial group (with all the dedicated black special interest groups), companies adopt a “better safe than sorry” strategy — and I don’t blame them.

Why rock the boat when you can just make a diverse ad to maintain good social standing. Moreover, most companies aren’t suffering as a result of diversity initiatives in advertising (allegedly no negative purchasing implications overall — according to available research); so keep the playbook going.